UNAM

VIN News Service photo

The School of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Husbandry at the National Autonomous University of Mexico became in 2011 the first, and so far only, veterinary school in Latin America to be accredited by the American Veterinary Medical Association Council on Education.

First of three parts

Lee este artículo en español

The year before Dr. Mayra Fortozo finished veterinary school at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, the program became accredited in the United States. Fortozo heard some buzz about it but paid little attention.

Accreditation by the American Veterinary Medical Association Council on Education opened a direct professional path for graduates of the school in Mexico City to work in the U.S. or Canada. Fortozo, though, planned to practice in her home country. Finishing her undergraduate degree in veterinary medicine in 2012, followed by an advanced degree in dog and cat medicine and surgery, she opened a clinic in her nation's capital.

In time, Fortozo started feeling restless. During a visit to Toronto in 2019, she fell in love with the city's multicultural vibe, its feeling of safety, its green spaces and its location "beside a lake so immense that it looks like the sea."

"Yep," she thought, "that's the city for me." Deciding to look for work in the Canadian city, she took the North American Veterinary Licensing Examination in late 2020, passing the 360-question test given in English on the first try.

Finding a job was trickier, owing to travel restrictions imposed during the Covid-19 pandemic. Not to be deterred, Fortozo responded to a Facebook post by an employment recruiter based in Canada.

Within a day of reaching out, Fortozo got life-changing news: "There's a company that's interested," the recruiter, Elsa Garcia, told her. The company, VetStrategy, manages more than 360 practices in Canada. Fortozo aced the interview and landed a job paying 10 times her practice-owner income, located right where she wanted to be — downtown Toronto.

With that, the 35-year-old practitioner became part of a small, potentially growing wave of UNAM alumni who have left Mexico in response to unprecedented demand for veterinarians elsewhere in North America. Recruiters such as Garcia, owner of Lazos Consulting Inc., see opportunities for more veterinarians like Fortozo to work internationally, which she says "opens them to a world of possibilities, while reaping better compensation and a more comfortable lifestyle."

Garcia, a multilingual Mexico native based in Toronto, traces the boom to the start of the pandemic in 2020, when demand for veterinarians around the world ramped up. Whereas hiring in many industries slowed during lockdown, veterinarians, as essential workers, remained coveted employees, a status that has only solidified in the past two years. "I'm struggling to find vets for my clients," Garcia said.

Karla Hernández has an expansive view of the trend. As director of the jobs center at UNAM veterinary school, she has seen a distinct rise in interest among international employers since 2020. "Right now, there is a significant boom, or bombardment, of companies that are looking to contract Mexicans," she said.

A quick look at the Facebook page that Hernández manages for the program shows job postings in the news feed from, for example, a recruiting firm in Canada and an animal hospital in the Bronx, New York.

Employers and their agents are working with Hernández to build enthusiasm for and awareness of working in the U.S. The university is looking to support students however it can, she said. "What we want is for them to have good jobs."

Few have pursued international licensing so far

Statue

Up to now, relatively few UNAM graduates leveraged their school's accredited status to seek jobs in the U.S. or Canada, judging from the number who have taken the NAVLE, an exam required to practice north of the border. The International Council for Veterinary Assessment, which oversees the test, does not divulge how many graduates of a given institution take the NAVLE, but UNAM has proxy data: Those wishing to take the exam need a letter from the school confirming their attendance and year graduated. According to the school, from 2015 through May 12, it had given out 125 such letters.

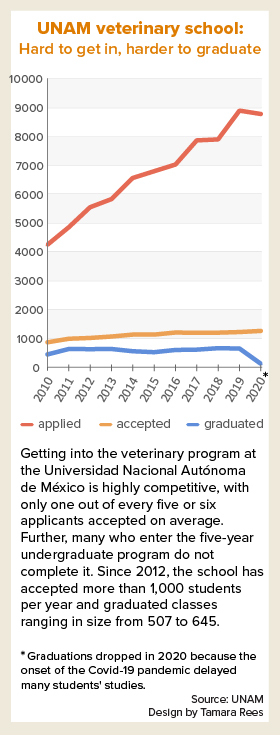

Considering 500 to 600 or more graduate during most years, that's roughly only 3%.

"I don't think the students fully understand the blessing they have, to have the university fully accredited," Garcia said.

Fortozo, the 2012 graduate, knows of no one else from her class who's left Mexico to practice elsewhere in North America. "Not many people are willing to do that," she said.

"First of all, you need to have the language," Fortozo explained. "I think that's a big barrier because an advanced level of English is required as a first step in order to apply for the NAVLE."

Dr. Mayra Fortozo and friend

Photo courtesy of Dr. Mayra Fortozo

Dr. Mayra Fortozo, right, celebrates graduation in 2012 with one of her best friends from veterinary school, Dr. Alfonso Macedo; the Central Library of UNAM is behind them. Today, she works at a companion animal practice in Toronto, and he's in equine practice in Mexico City.

Garcia agreed that fluency in English — or French, for those interested in relocating to Québec Province — is an issue. She recalled a meeting she had with around 90 students, of whom she estimated fewer than 10 spoke English comfortably. None spoke French.

The fee to take the NAVLE is another impediment. Sitting for the exam outside the U.S. or Canada costs US$1,065, including a $345 international testing site charge.

Dr. Rodrigo Cedillo Flores, a 2018 UNAM graduate working in Halifax, Nova Scotia, explained: "Unfortunately, not all the students have the money or support to cover the expenses of the NAVLE, and it's not a requirement to be a veterinarian in Mexico. So they don't see it as part of our program, and some wait until they have enough money."

The school recognizes the obstacles. Hernández said, "We are now promoting the NAVLE, and some [students] are preparing to study the language."

The private sector is stepping in, as well. Esmeralda Lozano is a headhunter at Staffbridge, based in Guadalajara. Since September, the veterinary employment firm has been coaching UNAM graduates for jobs in the U.S., helping them study for the NAVLE using simulated tests, and providing English-language classes, according to Lozano. She said the firm is prepared to invest a year to ready each candidate for employment abroad.

Since January, the firm has interviewed 100 applicants, selecting 20 with the necessary language skills for the job-preparation program, she said. The candidates are now preparing for the NAVLE and polishing their English.

Successful applicants will be reimbursed by their respective employers for the costs of their test, visa and relocation, according to Lozano.

She finds interest among UNAM graduates to be high because salaries in Mexico do not compare. She said veterinarian pay in Mexico is around US$1,000 a month — if you're lucky. Minimum salaries where she places applicants are $6,250 per month.

Garcia, the recruiter in Canada, said that as more UNAM alumni work abroad, their peers in Mexico are exposed to the possibilities for themselves. "They'll see on social media: 'Hey, I'm in Canada' or 'I'm in Texas,' 'and I have my own place. I'm going here, I'm going there,' and they're like, "Oh!"

Accreditation achieved amid controversy

Banfield Pet Hospital, Mexico City

VIN News Service photo

Banfield Pet Hospital opened a clinic on the UNAM campus in 2005. Veterinary students usually do two-week rotations at the companion animal practice, which is open to the public.

That only a small fraction of graduates so far have taken their careers outside of Mexico belies predictions made when UNAM was being considered for AVMA accreditation. A number of U.S. practitioners voiced concern that UNAM graduates would flood north, competing for scarce jobs.

The economics of the time were very different: The country was still feeling the effects of the 2008 housing market collapse. Businesses were in a holding pattern, at best. Moreover, new graduates from U.S. veterinary schools were entering the workforce with six-figure debt, whereas UNAM graduates had none — tuition at the public university is virtually free. Consequently, some feared that UNAM graduates would outcompete their U.S.-educated peers because they could afford to take jobs for less pay. Conversely, some feared unscrupulous employers would exploit veterinarians from Mexico by offering lower wages. Some were dubious that the veterinary education at UNAM was comparable to that of the U.S.

The controversy was driven in part by the fact that Banfield Pet Hospital, one of the largest veterinary practice chains in the U.S., with, to some minds, a doc-in-the-box reputation, had built a companion animal clinic on the UNAM campus in 2005. Its top executive advocated AVMA accreditation of the school while expressing interest in hiring its graduates for jobs in the U.S.

The accreditation quest took many years and included a rejection in 2010. But the school appealed, and in March 2011, UNAM became the first, and so far only, veterinary program in Latin America to achieve accreditation by the AVMA COE, which is the only accreditor in the U.S. of veterinary schools.

Veterinary education and culture in Mexico

Long known for serving students from every income bracket, UNAM is a publicly funded institution and one of the most competitive schools in the country, renowned throughout Latin America. Its School of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Husbandry, one of about three dozen veterinary education programs in the country, enjoys the same high regard. It was founded in 1853, making it the oldest public veterinary school in North America.

Historically, the profession in Mexico focused mostly on farm animals. But the past two decades have brought a "great revolution with companion animals, specifically dogs and cats," according to Dr. Claudia Edwards, a UNAM professor in bioethics and animal husbandry of dogs and cats. Echoing a statement made in a growing number of cultures, she said, "Society is seeing animals much more as family."

Edwards said a big change came in 2017 when Mexico City, which is a state, enshrined animals as sentient beings in its constitution. The recognition grants certain rights to animals, including a right to adequate shelter and a right to not be treated cruelly.

That led veterinarians to alter their approach to animal care. "Veterinarians had to change our language," she said. "Before, animals were seen as things."

It also changed practices such as mass breeding of pets. Before, clinics would double as pet stores, selling dogs, cats, chickens and rabbits. No longer, she said: "Clinics don't sell them; they promote adoption."

The Médico Veterinario Zootecnista (MVZ) degree program at UNAM is a five-year undergraduate course open to students directly from high school. Since its accreditation in 2011, UNAM also has provided postgraduate specialty training in everything from cats and dogs to wild animals and horses. The program includes hands-on practice at seven ranches, as well as multiple hospitals on campus.

The program is highly competitive. In 2021, fewer than 18% of 7,108 applicants were accepted, according to university figures. The number of applicants has nearly doubled since 2005. The program costs the equivalent of about one U.S. penny per semester for Mexican citizens.

Attrition is high. Sometime in their second year, many students find the coursework too difficult and drop out, according to Dr. Alejandro Cervantes, head of oncology at UNAM's small animal teaching hospital.

"For example, immunology and virology are very difficult classes," he said. "[W]hen they are placed in those classes, they realize this isn't for them." Nearly all students who make it through the first few semesters graduate, he added, with the vast majority going on to work at private clinics.

Retrospection

Coming or going, hurdles are high

In a tense online conversation that began shortly after the UNAM program was accredited in 2011, Dr. Kate Thompson of Florida was among the American veterinarians who expressed worries about the possible effect on the U.S. job market and new graduates from U.S. schools.

On a message board of the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of the VIN News Service, Thompson wrote:

"I am primarily concerned with a flood of foreign students hitting a market with little to no debt, competing against students from universities in the U.S. that I have supported with my tax dollars."

A clinic owner at the time, Thompson added: "All we business owner[s] are trying to do is prevent a large corp[oration] from dumping low-paid vets into the system that will cause salaries to drop."

Some agreed. Others pushed back against what they perceived as xenophobic and racist attitudes.

Asked for her thoughts today, Thompson first re-read her posts. "Wow, I was spicy back then," she remarked, a touch sheepishly. "I'm not as spicy, 10 years on."

Thompson said she is glad the impact of UNAM accreditation on the U.S. veterinary workforce market turned out to be negligible, but she still believes in the value of protecting the market for homegrown veterinarians. And she is gratified that veterinarians who feel the same way conveyed that message loudly and clearly to leaders of the AVMA and its accrediting body, the COE.

Indeed, the question of foreign-school accreditation occupied the AVMA for years afterward, and the vocal dissatisfaction of many members with the COE stemming from that issue, among others, drew scrutiny by the U.S. Department of Education. After the agency ordered the COE to reach out to its critics and regain their confidence, the controversy gradually subsided.

Dr. Juan Miguel García Ripoll, a 1984 UNAM graduate and owner of a hospital for small animals in Mexico City, followed the controversy closely.

He tried at the time to allay the anxieties, telling his U.S. counterparts on the VIN message board that no, a flood of Mexicans was not about to take their jobs at lower salaries.

His words came true. "I was the prophet who assuaged those fears," García said in a recent interview.

Even considering the heightened mutual interest today between employers in the North and UNAM graduates, García doesn't anticipate Mexican practitioners will leave the country en masse.

The language barrier is one reason; another, he said, is the high level of education in the U.S., where veterinary medicine is taught in professional schools to college graduates.

"I don't see the UNAM as an exporter of veterinarians," García said. "The UNAM has a good level of education in Mexico, but it would be very difficult to compete with the great universities of the United States."

Dr. Benjamin Macuil-Rojas, a student member of VIN when UNAM accreditation was debated, read the heated discussions as they unfolded, refraining from joining the fray. He admits today that he was "a little bit" offended.

"You see ... a lot of doctors talking about how we're not going to be good [veterinarians]. Bringing salaries down for everyone else. When you read that, it's like, so loaded and so difficult that people see you that way when they don't even know you; when they don't even know the school," he said.

Dr. Paul Pion, president and co-founder of VIN, was a prominent critic of the AVMA's interest in accrediting veterinary schools around the world. The same year that UNAM was accredited, so was the Caribbean school Ross University. (They were not the first foreign programs to gain AVMA accreditation; the first was in the Netherlands in 1973. Today, 16 schools outside the U.S. and Canada are AVMA-accredited.)

Like Thompson, Pion said his abiding interest was to help U.S. veterinary school graduates enter an accommodating job market, which, at the time, was much looser. UNAM's application for recognition, he said, became a lightning rod for the broader concern.

Pion said he didn't expect even then that UNAM would be a source of many job seekers in the U.S. but noted, "We did get a flood from foreign accreditation: One-fifth to one-quarter of new grads today are coming from foreign schools, including the Caribbean. So our concern was, if it looked like our profession was facing an oversupply, which would negatively impact salaries and young graduates and their chances for jobs ... then why were they pushing [to accredit more schools]?"

He allowed that he did not anticipate how the job market for veterinarians would unfold. Fast forward to 2022, and demand has reached perhaps its highest point in history.

Macuil-Rojas, who graduated from UNAM the year it was accredited, happens to work in the U.S. now — for Banfield. That connection occurred randomly. No pipeline, formal or informal, was established to direct UNAM graduates to the company. Considering the state of the market now, he believes U.S. practices on the whole could benefit from a closer relationship with the university.

"These guys need doctors," said Macuil-Rojas, an area chief of staff overseeing five Banfield practices in greater Phoenix. "It's a major crisis right now."

Attempts by VIN News to set up interviews with veterinarians for this report tell the tale. Several were too busy with work to talk. One veterinarian in Arizona who found time after a few false starts explained: "I'm the only doctor right now. Sometimes I have to cover [extra shifts]. We used to have four doctors, and it went down to only one now."

Macuil-Rojas said there's a mismatch between demand and supply on both sides of the border that could be eased with better coordination, helping to reduce burnout in the profession.

"We see how doctors in this country are suffering," he said of the U.S., while noting that Mexico has 30-plus veterinary schools, including three in Mexico City alone. "Why not give the opportunity to someone who wants it, who can do a great job, who can help as many pets as they can?"

Next: What it's like moving to the North