Mary Rawlings-Spencer

Photo courtesy of Dr. Mary Rawlings-Spencer

Dr. Mary Rawlings-Spencer, shown as an intern, remembers her training year (1999-2000) as a lot of work for little pay. Today, as the intern director for a multi-specialty practice, she strives to improve trainee salaries, benefits and treatment.

Seven years ago, Dr. Kristen Brennan had barely enough money to get by. The veterinarian drove an old car with broken windshield wipers that she couldn't afford to fix. She considered the free doughnuts clients sometimes dropped off as a much-needed supplement to her diet. That was in 2015-16, the year she did an internship.

Brennan is one of many veterinarians who were reminded of their experiences as trainees working long hours for little pay after reading "Veterinary intern salaries in the spotlight," published March 4 by the VIN News Service. The article focused on efforts in the profession to increase intern pay, which averaged around $38,000 in the 2021-22 training year, according to recent research.

Internships, common in the year after graduation, are optional for those going into general practice, and recommended for most veterinarians wishing to pursue a residency on the path to becoming a specialist.

Anecdotes shared by veterinarians, spanning from 1968 to 2020, show that financial stress long has been a feature of being an intern. Many veterinarians say the experience was well worth the trouble, while others believe the system isn't sustainable. A few singled out hard-working spouses, supportive parents and even an old car for helping carry them through.

Their stories are drawn, with permission, from a message board of the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of the VIN News Service. Some anecdotes have been edited for style and length.

I was an intern in the 1968-69 class at the AMC [Animal Medical Center in New York City]. Pay was ± $6,500. The first $60 per month went to pay for parking in the underground garage a block away. "Special rate for interns!" My wife worked to make my internship possible.

Dr. Charles Newton

Hayward, Wisconsin

My internship (1999-2000): We were paid $19,000, up from $18,500 the year before. I rented a room in a house the clinic owned for about $300/month, so I felt rich. The experience was truly invaluable.

Dr. Rachael Carpenter

Blacksburg, Virginia

Oklahoma State intern here, 1999-2000. Man, I would have been over the moon with $19,000. My intern mate and I made about $9,000 for the year. There were supposed to be three of us, but they only had two for the year, as they decided to have an internal medicine resident instead. So there were two of us on call the whole year — in the clinic all day, maybe all night. I learned a lot, but it was hard-won, bought-dear. We figured out our hourly for the week once, and it was about a dollar/hour.

Now I'm the intern director at our multi-specialty private practice. I certainly strive to treat our interns better than I was, and we definitely pay better, with more benefits.

Dr. Mary Rawlings-Spencer

Annapolis, Maryland

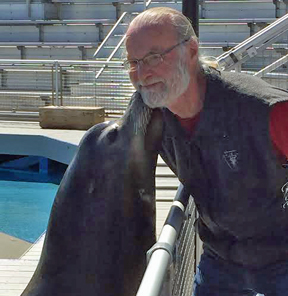

Charles Newton

Photo courtesy of Dr. Charles Newton

Dr. Charles Newton, pictured a few years ago at the New York Aquarium, recalls being paid about $6,500 as an intern in 1968. He credits his wife for supporting him through it.

I was an intern at Louisiana State University in 2006 — little pay and long hours like the rest. I hated it, but in the end I got what I wanted out of it: three more years of long hours and very little pay [as a resident]! It was a means to an end, and I'm glad I did it and would do it again.

I think many institutions that offer internships have a finite budget for interns, so higher pay would equal less spots. Not necessarily a bad thing, but everywhere I've been that had an intern program dealt with budgeting for intern salaries. The other factor is that interns cost money. I have had a lot of interns over the years and have had a lot of positive experiences with a lot of them, but at the end of the day, they cost money. I can be much more efficient without an intern. I don't have to worry about showing them anything or explaining anything. There is a limit to what you can pay someone that reduces efficiency.

I'm sure that makes me sound like a grumpy old man, and I guess maybe I am ... maybe I should have started with "when I was an intern ..."

Dr. Michael S. McFadden

Magnolia, Texas

In 2008-09, I was an intern at Iowa State. Due to staffing shortages, we spent most of the year (40-50%) on small animal emergency, a service that was staffed solely with interns and paraprofessionals. We worked long shifts, frequently hitting 80+ hours per week. We were scheduled 24 hours off every two months. My wife held down two jobs because I was never home anyway, and we needed the money.

I have no idea how much revenue we generated for the school (*lots*), but I do remember what we were paid for our time: $19,000. Assuming 40 hour weeks (ha!) for a year, that is $9.13/hour. I can say that actual pay for hours worked was below minimum wage. I have to believe that we can do better, especially in our institutions of higher learning.

Solutions? More pay, more structure, more limits on intern employers, and more respect for these young doctors seeking to improve their skill sets and take the next step toward specialty.

Dr. Kristofer R. Schoeffler

Pearland, Texas

2010 Ohio State intern here. $19,500 salary, 50-75 hours/week, 51 weeks = $7.65/hour - $5.10/hour depending on the rotation.

However, my take is that it was a whole lot better than what I made in vet school (negative $25,000/year), my quality of living was not bad, and it was an invaluable benefit to my education.

Dr. Travis Nick

Scottsdale, Arizona

For me, the internship [in 2011] was not the real hardship, as it only lasted a year. The residency was the hard slog. I definitely paid for groceries with change a few times, and I sold my car at the end of my residency for $300 scrap metal after hoping that it would not break down before the end of my residency. The interior lights stopped working and, at some point, the speedometer stopped working, so I just kind of guessed how fast I was going. I am quite thankful for my youth and health during this time because I was really one minor financial setback from giving it all up.

I worked relief at the university extension and at 'satellite hospitals' during [the] internship (they paid you $700 for a relief shift which is what I made in a week) to supplement income and kept the windows down in the middle of winter to stay awake on the drive home if I worked all day Friday. … Would I do it again? No way! Am I grateful for my education and experience? Yes.

I don't think the current system is sustainable. I think this issue ties directly into diversity and inclusion, we are the least diverse health care profession, and I think this problem is worse, from personal observation, in the specialty community.

Dr. Bryan Marker

Redwood City, California

Bryan Marker

Photo courtesy of Dr. Bryan Marker

While Dr. Bryan Marker is grateful for what he learned during his internship and residency, he said he wouldn't do it again.

When I did my internship (rotating private practice, circa 2015), it was one of the better-paying ones in the country. Didn't matter, though, because it was also in one of the highest cost-of-living areas in the country. Seventy-five percent of my monthly salary was spent just on rent. I burned through $10,000 in 'savings' (really, loans left over from fourth year). I was food insecure during my internship. I would pay attention to which clients often brought in free doughnuts so that I could snag some. It was desperately needed. My car was paid off (fortunately) but was also 20 years old. My windshield wipers broke in January (in the Northeast), and I couldn't afford to fix them until after I started my 'real job' in August.

About six months in, my parents visited, realized just how bad things were, and insisted on taking over my grocery bill. I'm not sure what I would have done if they hadn't. Maybe food banks, but I was always at work when those kinds of services were open. I was working 12-hour days most weekdays, 14 to 18 hours on the weekends, with one day off a week (always on a weekday). Lectures and journal clubs, when they happened, were pretty much always on my day off, so I was sometimes in the building seven days a week.

When I finally got a real-person job, it took a long time to mentally adjust to just having enough money for basic needs. I drove that 20-year-old car until the brake lines rusted through. I slept on a mattress on the floor for six months because a bed frame felt needlessly extravagant. And I ended up with severe burnout and depression, which I've been struggling to manage ever since.

Dr. Kristen Brennan

Catonsville, Maryland

I graduated in 2020 from Dublin, did a general internship in equine medicine at a private practice that saw a literal "little bit of everything" in Washington. I got paid $35,000, and was provided housing on-site. I also got to keep whatever emergency fees I made when I started taking on call by myself. My intern buddy and I did the math one night and figured that we made ~$4/hour, plus our emergency fees. I got a lot [out] of my internship and would do the experience again, but the money I earned was just enough. I had very little at the end of the day to put into savings to be able to support my future self. If I had to be paying on my student loans and/or rent, I can tell you it wouldn't have been.

Now my story gets a little skewed because I ended up having health problems at the end of my internship that ended up necessitating surgery. … If it wasn't for my parents, I would be in a cardboard box because the meager savings I did cobble together vanished in the blink of an eye due to my medical bills. I am presently in Virginia working full-time as an ambulatory equine practitioner and [holding] a part-time job to make ends meet.

In general, the profession as a whole is doing a poor job of setting practitioners up for financial success, especially in the early years. I understand that I have had some extraordinary experiences so far, but I think it does highlight just how painful living on thin margins can be. Something has to give.

Dr. Angela Feiring

Richmond, Virginia

Correction: This story has been changed to correct the dates of Dr. Kristen Brennan's internship in the opening paragraph and Dr. Angela Feiring's location.