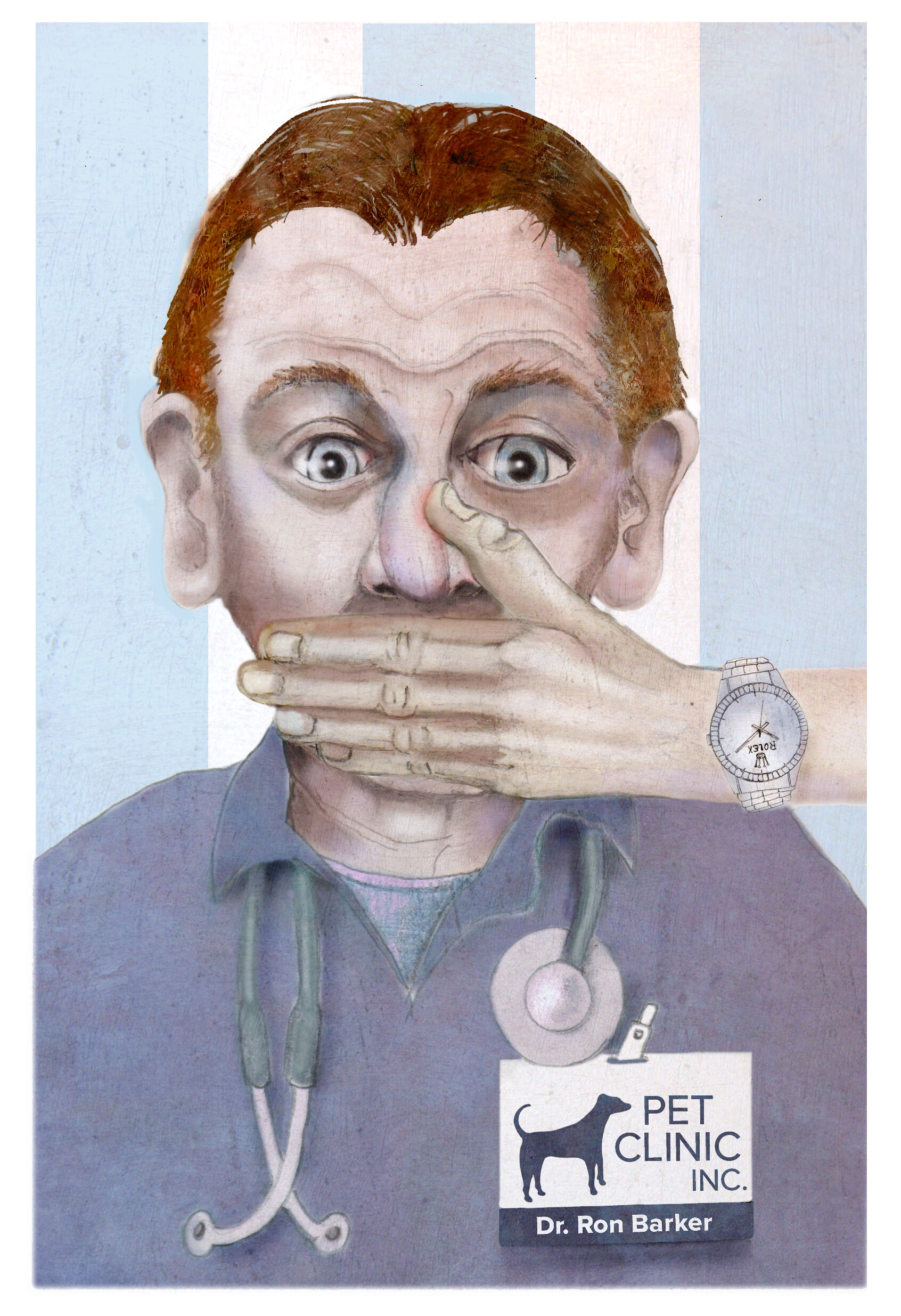

Hushed_v2

Illustration by Jon Williams

Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

When the veterinary practice where Dr. Jane Smith worked was sold recently to a consolidator, a condition was put on the table that she didn't expect.

The corporation that bought the animal clinic in the United States insisted on including a non-disparagement clause in her new employment contract.

As its name suggests, the clause was added to stop the veterinarian from saying anything negative about the buyer — even if it were true. And the restriction would be in place for the rest of her life, including when she no longer worked at the practice.

"They wouldn't budge on the non-disparagement part," Smith told the VIN News Service. "And it doesn't have an end date on it. So I can't disparage them forever."

Smith, who signed the contract because she wanted to keep her job, chose to use a pseudonym for this article and declined to name the consolidator, fearing that speaking publicly about the non-disparagement clause could be seen as disparaging.

The contract has had a broad chilling effect on Smith's behavior. She has been holding back on talking publicly about the impact of corporate consolidation in the veterinary profession, even generally. The consolidator, Smith said, explicitly warned her that she shouldn't write anything untoward on the message boards of the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of VIN News.

Many other veterinarians, Smith suspects, are in the same boat. And she wonders whether such clauses are stifling debate and distorting perceptions about the effects of rapid consolidation on the veterinary profession.

She indeed is not alone. Non-disparagement clauses are nothing new, having been applied for decades in various industries. But their use is becoming more common in a global veterinary community that recently started attracting big money from Wall Street and other financial hubs. Corporate consolidators now control as much as half of all revenue generated by U.S. veterinary practices, by the reckoning of Chicago-based consultancy Brakke Consulting.

The private equity firms and other large corporations that have been snapping up practices of late, often for lofty sums, are under pressure to generate high returns. And that can mean ensuring staff, past and present, don't damage reputations and thereby undermine the value of the businesses.

Ed Guiducci, a Colorado-based attorney who has been advising on sales of veterinary practices for 35 years, said non-disparagement clauses are becoming more prevalent. "The veterinary profession is much more sophisticated from a legal standpoint than it was 20 or 30 years ago, and especially in the last five or 10 years with the influence of Wall Street and private equity," he said.

All of the big corporate consolidators and many smaller ones are now adding non-disparagement clauses to contracts in some shape or form, Guiducci said, without naming companies. The clauses are inserted into a range of contract types, such as practice sale, partnership or employment agreements.

VIN News spoke to a practitioner who said she signed a non-disparagement clause when she sold her practice to BluePearl, a unit of Mars Inc., the world's biggest owner of veterinary hospitals. Unlike Smith's, though, her clause expired in five years. That practitioner also asked to remain anonymous for this article.

Mars and three other large consolidators — National Veterinary Associates, Thrive Pet Healthcare and Vetcor — declined to comment or did not respond to requests for comment.

Three other veterinarians who recently sold practices told VIN News that non-disparagement clauses were absent from their contracts ("This is news to me," said one), and many other practitioners did not respond when asked. The cases in which clauses were absent each involved sales to smaller consolidators, which may feel pressure to offer more attractive terms to compete for practices. "Clearly, you can get better terms if you're selling to an aggregator that doesn't own many practices," Guiducci said. "But they're probably not going to pay as much, either."

Guiducci maintains that non-disparagement clauses can be drawn up with reasonable intentions, especially considering how much damage negative comments from disgruntled senior staffers can do to a business's reputation and financial viability. He offers the example of two practitioners who team up to establish a practice. Both, he said, could agree to sign a non-disparagement clause as insurance, should they ever have a falling out.

He also notes that nobody is forced to sign a non-disparagement clause, though acknowledges that in the case of employment agreements, some veterinarians may feel it's the only way to keep their jobs.

"I can understand how some doctors may feel like their ability to speak their opinion is limited, but on the other hand, if you're selling a business, you may be getting millions of dollars from this company and they want something in return," he said. "I can see it from both sides."

Dr. Beth Fritzler, a practice-management consultant at VIN, accepts that non-disparagement clauses may be justified — to a point. "It isn't necessarily unreasonable for a buyer to not want the former owner bad-mouthing the buyer after the sale, especially since a lot of what buyers are purchasing is the goodwill of the business," she said. "However, a lifetime gag order seems unreasonable."

Fritzler has encountered the clauses personally. She and her husband signed one when they sold their practice in 2018 to a consolidator, which she declined to identify. The clause expired five years from the sale closing or three years from the end of employment, whichever was later.

"Our particular clause did not mention any specific sites such as VIN but did list a fairly broad view of what constituted disparagement — basically, anything that reflected negatively on the business or consolidator," Fritzler said.

When is speech 'disparaging'?

Precisely what language constitutes "disparagement" can depend on the wording of the clause and how conservatively individuals choose to interpret the wording.

"What exactly is disparaging is usually vague — on purpose, so the veterinarian shuts down all speech related to the event," said Dr. Lance Roasa, a veterinarian and lawyer.

Roasa, also cofounder of a continuing education business, drip.vet, now owned by VIN, notes that non-disparagement covers a much broader range of speech than defamation because it applies even to statements of truth.

When advising veterinarians who are selling their practices, he said he usually tries during negotiations to insert language into the clause that specifies a direct, material loss in credibility for the other side. "Also, I would work to limit the target to one company, not an entire industry or group of companies," he said. "I would definitely push back on a life term."

VIN News reviewed the text of several clauses, with the names of the signatories redacted. One compels the signer to not "defame, disparage, criticize or otherwise speak of [the company] and/or their products or services in a negative, derogatory or unflattering manner." Another states the signer can't make disparaging remarks "to any person or entity or in any public forum" about the company, its affiliates, employees, customers and investors. Facebook and Twitter are mentioned specifically as platforms to which negative comments should not be posted.

Sometimes, the clauses state that signers aren't prevented from speaking negatively about the company when complying with certain laws. Some states legislate that non-disparagement clauses can't be used to prevent victims of unlawful acts from speaking up. At the federal level, a law called the Speak Out Act passed last year, preventing the clauses from being enforced to silence victims of sexual harassment or assault. The clauses also may be overrided by state and federal whistleblower protections.

Should a company decide that a veterinarian has breached a non-disparagement clause and attempts to claim financial damages, it typically would have to present tangible evidence proving hurt.

"In enforcement, the issue is usually proving damages and linking verifiable money loss to the defendant's statements or publications," Roasa said. "However, the mere threat of a lawsuit is enough to make most people and veterinarians stop before they say or do anything remotely disparaging."

Guiducci said proving financial damage can be tricky, though that wouldn't necessarily prevent veterinarians from quickly finding themselves in hot water. Companies that suspect they've been disparaged, he said, could sue to request a court injunction preventing the veterinarian from saying anything else disparaging — and the veterinarian could have to foot the company's legal costs.

None of the sources contacted for this article could recall an occasion when a veterinarian was sued for breaching a non-disparagement clause. Guiducci, though, said he had one client who received a cease-and-desist letter because she posted something on a media site that a consolidator didn't like.

"What she said was factually accurate, but they felt like it put them in a negative light, and they were threatening her," he said. The veterinarian complied with the letter as requested.

And for people like Smith who are afraid to post negative comments about consolidators in general, are they being paranoid? Guiducci suspects they could probably get away with commenting, so long as they didn't name the company — though he said much would depend on the wording in their contract.

"Most of the language is talking specifically about an individual company, so if a person said, 'We think corporate consolidation is negative for the consumer,' the way most non-disparagement clauses are drafted, I think it would be fine," he said.

Still, he understands why Smith and potentially many more practitioners could be holding their tongues. Simply put, "People who are worried about the non-disparagement clause are going to be more cautious," he said.

This story has been updated to add a reference to a new federal law that prevents the enforcement of non-disparagement clauses in instances of sexual assault and harassment.