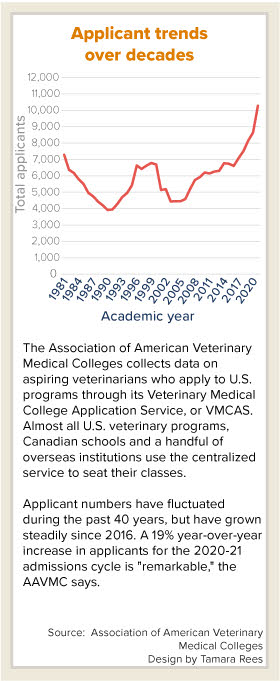

Jaws dropped this month when the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges released data showing 10,273 people applied to veterinary programs for the academic year that begins in 2021, representing a 19% jump from the year prior.

Even the group that collected the information was surprised. A write-up on the AAVMC website describing the one-year growth rate as "astonishing" is punctuated by a colorful graphic that shouts, "Wow!"

An annual rise in the number of veterinary school applicants is nothing new, but it's usually in the range of 6% to 7%. AAVMC's top data analyst doesn't expect the latest rate to be sustained, however, due to a number of factors — among them, COVID-19.

Lisa Greenhill, AAVMC senior director for institutional research and diversity, suspects the spike is an exaggerated display of the swings in higher education that usually coincide with economic downturns and, in this case, pandemic-related uncertainty: When life gets iffy, people tend to go to school

"I think a substantial part of the increase is probably people who would have slid into our pool over the next one to three application cycles — they were probably coming anyway," she said. "But again, the economy coupled with pandemic-related changes created a situation where folks are saying, well, 'I might actually have a shot this year,' and 'I need a plan because this pandemic doesn't seem to be abating.' "

Data showing the application spike comes from the AAVMC's Veterinary Medical Colleges Application Service, which acts as a clearinghouse for applications to 44 member institutions, most based in North America. Every U.S. veterinary school, with the exception of Texas A&M and Texas Tech universities, and three Canadian programs participate in VMCAS.

The number of VMCAS applicants has been on a steady climb since 2015, when 6,600 aspiring veterinarians applied to start school in fall 2016. Last year, VMCAS collected applications from 8,645 would-be veterinary students hoping to matriculate this fall.

"This year, not only did more students think about applying to veterinary schools, they were more apt to follow through," Greenhill said. Ordinarily, around 72% or 73% of individuals who start the VMCAS application process complete it. Most recently, it was 79%.

"We are in uncharted territory," Greenhill said.

Several internal factors could artificially inflate the numbers, Greenhill said. For example, AAVMC opened this year's application cycle in January, four months earlier than in years past, which enabled applicants to have more time to prepare their applications. Also, the AAVMC Office of Admissions and Recruitment provided more outreach to help applicants through the process.

"Plus, the pandemic made sure everyone was at home and had [more time] to complete their applications," Greenhill said. "Put this in the context that all graduate and professional programs see dramatic increases in the midst of economic uncertainty."

As the economy worsens, experts in higher education expect the volume of graduate- and professional-school applicants to balloon, as in the past. However, a coronavirus-driven recession brings the prospect of being educated remotely, which has hammered undergraduate enrollment figures, Greenhill noted.

"We really need to be paying attention to what's happening in undergrad," she said. "Everybody's all hung up about this major increase, but I look at it as a cautious high."

Lisa Greenhill

AAVMC photo

Lisa Greenhill, who has a doctorate in education, directs the AAVMC's research efforts, which include studies of national trends among veterinary school applicants.

Mulling the future of veterinary education, Greenhill shared her perspective in response to questions from the VIN News Service.

Can you elaborate on why you believe veterinary school's popularity might wane?

While this does appear to be the most fierce pool we've ever had, I don't believe it's sustainable, especially when you look at undergrad, which is a much smaller pool.

Across the board, undergraduate numbers are down significantly, and we're looking at specific declines in underrepresented and marginalized populations. And that means that veterinary academia will have potentially smaller pools to pull from in the very near future.

And this is coming ahead of a decline that's already projected. For example, the [high school] class of 2025 — kids born during the last recession — they'll be starting university. That is a more diverse pool but a much smaller population, as are the years that follow it.

It's really unclear what long-term implications of this pandemic-induced crazy time will be; we just don't know. But based on population, we do know it's likely there will be fewer students in general, very soon.

During the past decade, U.S. veterinary academia has rapidly expanded. Are new programs, such as those that opened this year at the University of Arizona and Long Island University, at all responsible for the upward swing in applicants?

People think applications skyrocket when there's a new school. They do not. We might see an increase of maybe 100 or 200 applicants, at the most. That is a drop in the bucket.

Is anyone saying that the increase in applicants means more seats are needed in veterinary schools?

I'm sure that some people will make the argument. Applicants always make that argument that there are not enough seats. I'm sure people will interpret it that way. But again, for folks who understand what's going on across higher ed in general, they know that an increase of this size should be treated as an anomaly and not as a predictor of being gangbusters forever. The writing is on the wall about the population shifts that are coming up down the line. And the big unknown for right now is, how many application cycles before we see how the pandemic will impact [veterinary academia]?

How might a surge in applicants impact tuition? Will the cost of education increase in response to rising demand?

I suspect that tuition across higher ed will be affected in a lot of different ways, and veterinary medicine is just part and parcel of that. We're in a pandemic. Enrollment across the board is down. Veterinary medicine … is not a moneymaker for universities, and undergrad is where they make their money and [human] health sciences is where they make their money. I predict a lot of pressure around tuition.

But here's the thing: Tuition is never going down. It's not; it's a fallacy. It could potentially be subsidized for [via allocations from state legislatures], but ... I live in a state [Virginia] where they don't even have free testing for COVID. I don't expect to see higher ed get more money next fiscal year when I cannot go to the health department and get a COVID test.

Do more applicants impact the quality of the applicant pool? Are they all qualified?

It's much too early to comment; we just don't know. I can say our long-term research around applicants to veterinary schools suggests the pool has always been very, very deep and there are many qualified students who don't get in. Our acceptance rate is in the high 40%, just under 50% maybe, and there are many, many, many applicants who are qualified who aren't admitted. It really depends on individual institutions and what their individual pools look like.