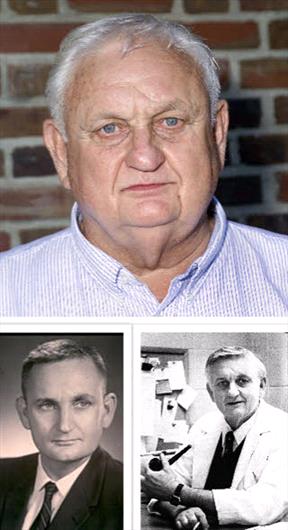

Dr. Skip Carmichael: an 'unforgettable character'

Skip Carmichael collage 320

Photos courtesy of the Baker Institute for Animal Health

Dr. Leland "Skip" Carmichael retired from Cornell University in 1997, having spent 38 years on the faculty of the College of Veterinary Medicine.

"Carmichaels aren't supposed to live this long," the renowned veterinarian and virologist Dr. Leland Carmichael often joked.

But Skip — as he liked to be called — lived to be 90, with levity and gusto. On July 27, the John M. Olin Professor of Virology Emeritus at Cornell University and an expert on canine infectious diseases, died peacefully in Ithaca, New York, three months after his wife of more than 60 years, Mary Margaret, died of cancer.

Reflecting on his father's life, Dr. Daniel Carmichael, also a veterinarian, said: "He was a carpe diem kind of guy. I think from him what I got was, 'If there's something you love, do it. Don't wait 'til next year. Don't waste a minute.' "

By all accounts, Skip was a dreamer and a doer who found time to enjoy family, travel, a good cigar and a poker game, all the while making significant achievements in the study of canine infectious diseases. Unofficially named "one of Cornell's all-time greats," Skip is remembered widely for his contributions to animal health, having been largely responsible for developing diagnostic tests and effective vaccines for several major diseases of dogs: distemper, hepatitis and canine parvovirus-2.

Equally with his professional accomplishments, colleagues remembered his singular personality. "He was an unforgettable character who had a host of friends throughout the world," said Scott Coonrod, director of the Baker Institute for Animal Health, in an announcement from Cornell University. "Skip was greatly admired and beloved by his many students and trainees."

Early years

Skip was born July 15, 1930, in Huntington Park, California. Soon after, his family settled in Arcadia, home to Santa Anita Park, a prestigious thoroughbred racetrack. After school, Skip walked horses in need of a post-workout cool down, and he developed an interest in animals. "I think he got a dollar a horse. His nickname back then was 'Slim,' and probably because he wasn't," said his son, Daniel.

Skip — or Slim — didn't mind the ribbing. Known for his gregarious personality, he's remembered as warm and self-effacing. "When your name is 'Leland Eugene,' a nickname is essential," Daniel said. "Dad told me it was after a cartoon character in the funny pages from back in the '30s who wore a big, baggy sweater. He always went by Skip."

Skip graduated in 1956 from the University of California Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine before arriving at Cornell, where he earned a doctorate in virology.

"His real love was the research," Daniel said. "I think he came to Cornell to be a pathologist but when he got to school there, they had no more vacancies in the pathology department, so they said, 'How about microbiology?' So he said, 'OK.' This was during the early days, when pioneering work on many of the important infectious diseases of dogs was done there."

In his first semester, he met Mary Margaret, who was working toward a doctorate in home economics. When Skip graduated in 1959, Cornell immediately hired him as a faculty member, where he stayed until his retirement in 1997.

Carmichael, Baker, Stephenson 288

Photo courtesy of the Baker Institute for Animal Health

Dr. Skip Carmichael (left) is pictured in 1954, in front of the newly established Cornell University Laboratory for Diseases of Dogs. Next to him are colleagues Drs. James A. Baker (middle) and C. Hadley Stephenson (right). The facility now is part of the Baker Institute for Animal Health.

Mary Margaret, too, was hired by the university to teach but resigned once the couple married and started a family. They had three sons: Daniel, Paul and John.

"They stayed Ithacans their whole lives," Daniel said, reflecting on his idyllic childhood.

"He was a genius in one sense, but in the other, he was just Dad," he continued. "We knew he was this scientist guy, because he'd get up and go to the lab and come home for dinner every day at 5 o'clock. Looking back on it, you hardly even knew you were growing up with this great veterinary virologist."

Canine parvovirus emerges

It wasn't until the summer of 1978, when the family cut short a two-week vacation in Cape Cod to return to Ithaca, that Daniel said he got a sense of his father's professional importance. "I didn't know what real veterinarians did, but I knew at that moment, my dad was needed," he said.

The threat was canine parvovirus, a relatively new and deadly disease that eventually reached pandemic proportions. Skip had spent two years studying the virus and searching for a long-term vaccine. Working with virologist Max Appel, a colleague at the Baker Institute, Skip created and perfected a modified live virus vaccine that still is used today.

That finding and his expertise landed him in a 1980 issue of People Magazine. Characteristically, Skip made light of it. In that same issue, Daniel recalled, "they had a story about Miss America or Miss Universe or something. So when my dad distributed the article to his friends, they got a copy with her face cut out and pasted on his body.

"He was just very extroverted and funny," Daniel continued. "Everyone knew him as just Skip, and he always had time to tell some story about something."

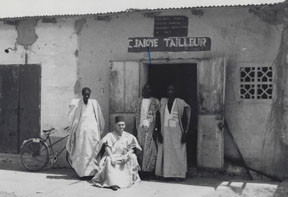

Carmichael in Africa 288

Photo courtesy of Dr. Daniel Carmichael

Dr. Skip Carmichael spent several months in 1965 in Mali, Africa, where he helped start a laboratory to produce a vaccine for rinderpest, a viral infectious disease that affects cattle and domestic buffalo. He is pictured seated with an unidentified group of men outside what appears to be a tailor shop, all wearing boubous. "He loved that traditional robe so much, I think he pretty much wore it every night in Africa, and then at home," recalled his son, Dr. Daniel Carmichael.

One such story involved Turkish coffee, which Skip grew fond of during his parvovirus research. "Since they used radioisotopes in the research, there were strict protocols on what could be stored in the refrigerator," Daniel said. When asked how he got away with storing his coffee there, Skip showed that the jar was labeled "Infected Dog Feces."

"No one ever found his coffee," Daniel said.

Brucellosis and beyond

In 1966, Skip was first to isolate canine brucellosis, a bacterial infection of the reproductive system that began appearing in beagles. The finding distinguished the bacterium from the Brucella species that infects cattle, sheep, pigs and other species, and led to a rapid slide agglutination test (a blood antibody test that detects infection) to diagnose B. canis.

Distinguishing between the Brucella pathogens was a matter of life and death for dogs. "If your dog had bovine brucellosis, it would have to be destroyed, because it set off alarms for agriculture," Daniel explained. Discovery of the newly recognized species saved the lives of dogs that might otherwise have been misdiagnosed with bovine brucellosis and euthanized.

"I think my father was very proud of that work," Daniel said.

Skip also did foundational work on canine herpesvirus and canine adenovirus types 1 and 2 (type 1 causes infectious canine hepatitis; type 2 is associated with canine infectious tracheobronchitis, or kennel cough) that led to declines of those diseases, as well.

Highlights from his long list of honors and accolades include the 1975 Gaines Award, conferred by the American Veterinary Medical Association for contributions to animal health, and the 1980 Gaines Fido Award, conferred by the American Animal Hospital Association for his parvovirus research. He received an honorary doctorate degree in 1994 from the University of Liège in Belgium, and in 2012, was granted the Mark L. Morris Lifetime Achievement Award from Hill's Pet Nutrition in recognition of his efforts to eradicate canine diseases. Throughout his professional life, he sat on the editorial boards of 10 scientific journals and co-authored more than 100 research articles.

Daniel, who is board certified in veterinary dentistry and practicing on Long Island, said he never felt pressured by his father's success. "My decision to become a veterinarian didn't really occur until after I got into undergraduate college and found out I probably wasn't going to be a marine scientist ... and my rock-star career wasn't going anywhere."

Early on, Daniel said, "I didn't really know what real veterinarians did, because Dad's version of veterinary medicine was spending a lot of time at the laboratory and vetting our own dogs on the kitchen table."

His brothers work in unrelated fields: Paul owns an investment company and John works as a drug and alcohol counselor.

Their father, Daniel said, "never really expected or wanted any of us boys to become veterinarians. He always just wanted us to find something in life that we loved. To us, that was his message."