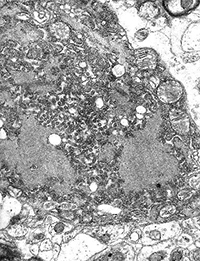

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention image

This electron micrograph created in 1975 shows the rabies virus as well as Negri bodies, hallmarks of rabies encephalomyelitis in certain nerve cells of the brain.

Dogs and cats in rabies quarantine in Massachusetts may be released after four months rather than six months under state regulations updated to align with new national guidelines.

In addition, dogs and cats with proof of vaccination at some point in their lives are now considered up-to-date as soon as they receive a booster, even if the booster is overdue. The new rules replace a rigid vaccination protocol that had resulted in some pets receiving shots annually of vaccines that are labeled for three years, or being placed in a months-long quarantine even if they had a history of vaccination.

In a letter notifying veterinarians of the changes that took effect July 29, Michael Cahill, director of the Division of Animal Health in the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources, called the new rules “far simpler and less burdensome for animals and their owners.”

Practitioners say the same.

“It is hugely beneficial all around, and is based on science rather than a legislative rule,” said Dr. Amanda Cronin, a veterinarian in Uxbridge, Massachusetts. “More pets will be considered up-to-date, fewer pets and families will be under the stress of prolonged isolation/quarantines [and] animal control officers can focus on more urgent problems.”

The change in Massachusetts — and coming to other states, as well — follows changes in the Compendium of Animal Rabies Prevention and Control, a guide for state and local jurisdictions in handling rabies, a fearsome, untreatable, deadly disease of mammals, typically spread by the bite of an infected animal.

The latest compendium, published March 1 in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, (JAVMA) reflects recent research led by the Kansas State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory that rabies booster shots in dogs and cats overdue for them are as effective as — and perhaps more effective than — booster shots given on time.

That information enabled Massachusetts to do away with a complicated vaccination scheme known as “primary series.” The primary series was an animal’s first rabies vaccination and first booster. The booster had to be administered between nine and 12 months of the first shot — “not a day early, not a day late,” a state information sheet specified. Unless the primary series was completed on schedule and documented, an animal’s successive boosters would be good legally for one year only, even if the vaccine used was good biologically for three years.

“It was a pain trying to explain to people why their 14-year-old dog with a three-year rabies certificate who had been getting its rabies vaccination every three years since it was a year old now needed a new one-year vaccination because the client did not have the proper primary-series documentation, or that the rabies vaccination about to be given could only be good for one year because the pet was one day late for its vaccination,” said Dr. Adam Arzt, a veterinarian in Milford, Massachusetts, in a post on the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession. Arzt called the revised rules “great.”

Cronin echoed the sentiment. “I am so happy to not have to worry about the ‘primary series" timing anymore,” she posted. “Telling someone they were one day late or one day to early to qualify for a three-year rabies vaccine was a pain.”

While the old rules may have seemed unnecessarily rigid, Dr. Catherine Brown, Massachusetts’ public health veterinarian, said they made sense at the time.

“Imagine you work for the government in any state. And you’re responsible for making sure that you’re preventing and controlling rabies in your area,” Brown posited. “Your primary goal is, you don’t want people to get rabies. You get a phone call from a veterinarian one day about a dog bitten by a raccoon, and it was only a day overdue [for its booster]. One day? You say OK. The next call, it’s an animal five days overdue. You’re like, ‘Well, does five days make a difference? Does 14 days make a difference?’

“There has been a significant lack of data on which to make better recommendations,” Brown said. “That is why the paper from Kansas State was so significant. It actually provided the data.”

In the study, researchers measured rabies titers — the concentration of rabies antibodies in blood serum — in 74 overdue dogs and 33 overdue cats. Some dogs were overdue by as much as three years, and some cats up to nearly four years. But all developed a strong immune response within 15 days of receiving boosters.

The research was led by Dr. Mike Moore, a veterinarian and project manager in the Rabies Laboratory of the Kansas State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, and published Jan. 15, 2015, in JAVMA.

The publication garnered much attention and excitement, said Brown, who also serves as co-chair of the committee that produces the rabies compendium. “I got a lot of questions after that paper came out, people asking, ‘Can we start thinking about rabies control differently?’ ” Brown said.

She is pleased with the recommendations that resulted, saying, “I think it’s a nice balance between treating the animals a little more appropriately based on science and still protecting the public.”

Two weeks in, the revamped rules in Massachusetts already have benefited two of Cronin’s patients. In her semi-rural community, she explained, “We get a lot of bite wounds in the summer.” Bite wounds of unknown origin are regarded as a potential rabies exposure.

A dog brought in last weekend had been due about 10 days earlier for his rabies booster. “He would have needed the six-month quarantine” under the old rules, Cronin said. Instead, he was given a booster and his owner was instructed to monitor him for 45 days.

The second animal, an indoor-outdoor cat, was overdue for his rabies shot by six to eight months, Cronin recounted. “Instead of quarantine, I boostered him and said, ‘Please keep him in for 45 days.’

“People still complain about 45 days,” Cronin added, “but now I can raise an eyebrow and say, ‘Do you know what the law used to be?’

Cronin said she also has patients, mostly cats, that are in the midst of a six-month quarantine, a big deal for pets accustomed to spending time outside. “It’s extreme stress on the cat and on the owners,” she said.

Under the old protocol, dogs and cats in quarantine would not receive booster shots until the fifth month. Now they can be boostered immediately and quarantined for only four months. The shorter quarantine is one of the new recommendations in the 2016 rabies compendium. Cahill, the state Division of Animal Health director, said in an interview that the shorter period follows evidence that rabies incubation in dogs and cats is four months or less. In Massachusetts’ experience, he said, “The longest incubation period we had for an animal under quarantine that did become rabid was three months and two weeks.”

Brown said Massachusetts’ quick action on updating its approach to rabies was due in part to an initiative by Gov. Charlie Baker asking state departments to review their regulations with an eye toward streamlining procedures and eliminating outdated rules.

“The timing ended up being essentially perfect, with the [subsequent] publication of the 2016 rabies compendium, compounded by the fact that I’ve been working in public health with our Department of Agriculture [which oversees rabies control in the state] for 10 years so that we have developed a really good relationship,” Brown said. “The combination of all those things allowed us to react very quickly.”

Implementation of the new rules was sped up further when the state put them forth as emergency regulations, effective immediately.

Cahill said he pushed for a speedy adoption because of the wide impact of the changes. “We said, ‘Look, this is going to affect a lot of animals under quarantine. It’s going to be a huge benefit for people who are being burdened by existing regulations.’ ”

He estimated that 750 to 1,000 dogs and cats will benefit from the shortened quarantine period alone.

Massachusetts’ hustle notwithstanding, it was not the first jurisdiction to update its rabies regulations. Tri-County Health Department in Colorado, serving Adams, Arapahoe and Douglas counties, adopted the compendium’s new recommendations as soon as they came out in March.

Officials had been aware that changes in the national recommendations were coming and prepared to follow the updated advice as soon as possible, said Jennifer Chase, manager of the department’s Disease Intervention Program. “We were excited,” Chase said. “We were right on it.”

Brown said that some states, such as Texas and Oklahoma, already had more permissive rules than the compendium recommended. “It’s working for them, so they’re not needing to make changes,” she said.

She added, “Rabies regulations vary quite widely across the country, appropriately, because I think rabies epidemiology varies.” For example: “You don’t have raccoon rabies in Oregon, like you do in Massachusetts, which is a game-changer. Oregon has bat rabies. It’s very, very different.”

States also vary in the speed in which they adopt or revise regulations. Louisiana, for example, is in the process of changing its public health sanitary code to reflect the compendium’s latest recommendations, said Dr. Gary Balsamo, the state public health veterinarian. “These changes were submitted immediately after publication of the compendium,” he said. “However, the changes will likely not be in the code until December.”