If a starry-eyed, wannabe veterinarian approached Dr. Andrew Mackin with news of acceptance at the prospective student’s top-choice school — and the school happened to be the student's most expensive choice — Mackin would have this pithy response:

“Don’t do it.”

A professor and interim department head of clinical sciences at Mississippi State University College of Veterinary Medicine (MSU), Mackin has watched nearly two decades’ worth of students, including members of his own family, graduate and step into their careers.

In that time, Mackin has observed an enormous dichotomy between students who leave with a manageable debt load and students who don’t.

“Each year, I see students with a high debt load that have to choose a job that pays well, instead of following their ‘dream’ career path,” Mackin said in an email. “It is debt, and debt alone, that severely limits their choices.”

He added: “Veterinary students are too motivated and smart and talented, and have given up too many years of their life in education, to then be forced to have to settle at the very moment they achieve their degree. Or to ‘settle’ by, for example, further deferring life choices, like starting a family.”

Mackin’s recommendation to pay close attention to finances when choosing a school is common advice nowadays.

Lauren Pangburn, who will be attending the University of California, Davis, in the fall, said she encountered it frequently during her decision-making process. Dr. Shweta Trivedi, a member of the American Pre-Veterinary Medical Association advisory board, said she believes most advisers want students to make cost “factor number one.” In online forums, the same guidance often sweeps the boards.

On the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession, a discussion thread titled “How should students pick a veterinary school?” includes these responses:

- “Honestly, I recommend to all pre-vet students that they make cost their number-one deciding factor.”

- “Get into the least expensive school you possibly can ...”

- “Price is paramount.”

For prospective students who have dreamed of becoming veterinarians since tending to stuffed animals, that advice might seem draconian, and not everyone agrees with it. But the advice is not given lightly by those who believe it — it’s rooted in the reality of a profession that has changed dramatically, and in the sometimes painful experience of those who now endure a heavy burden of student debt with salaries that don’t keep up.

According to the American Veterinary Medical Association, the gap between average debt and average income has widened quickly. By AVMA calculations, the debt-to-income ratio has increased from about 1.2-to-1 in 2001 to about 2-to-1 in 2015.

That is thanks to the rapidly increasing cost of veterinary education, which has more than doubled over the past 16 years at U.S.-accredited schools. Meanwhile, starting salaries have not kept pace, even decreasing between 2008 and 2012.

The 2016 AVMA and Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges Report on the Market for Veterinary Education lays out telling numbers derived from results of a survey of graduating seniors in 2015. That year, the average starting salary was $70,117 for those going into private full-time practice. Including those who accepted residencies, internships, advanced education training or public practice, average starting salary was $55,000.

The average debt of new veterinary school graduates who borrowed money for their schooling was $160,435. The average debt of all new graduates, including those with no debt, was $142,394. The range was zero to more than $450,000. As in most years, the vast majority of new graduates — more than 88 percent in 2015 — reported having educational debt.

How new-graduate debt should be calculated is a point of debate in the profession, and some maintain that the AVMA figures are on the rosy side. Among critics' questions are: Should the average include students without debt? Should it include the debt of U.S. graduates from Caribbean programs and other U.S.-accredited foreign schools? Should it include educational debt acquired before veterinary school? How accurate is self-reported debt?

But regardless of the formula used, the figure is well into the $100,000. The amount that takes a serious toll, resulting under traditional repayment plans in mortgage-size monthly student loan payments.

“The rapid and persistent expansion of this gap between debt and income for new veterinarians represents a major problem for the profession and a current focus of research efforts,” reads the 2016 AVMA Report on Veterinary Markets.

Not the good old days

The veterinary profession is mired in concern about the surging cost of school, dismal debt-to-income ratios, and mental health and suicide rates. A 2013 New York Times article titled “High debt and falling demand trap vets” drew national attention to the financial issues.

Mackin argues that by making an early decision based on finances, future decisions don’t have to be.

“Veterinary school is four years of a veterinarian’s life,” Mackin wrote on the VIN message board. “In contrast, debt load, if it is high enough, affects the rest of the veterinarian’s 30 to 40 year working life, and perhaps beyond, and severely impacts life choices for decades.”

Dr. Ariana Anderson, who attended Michigan State University, is well aware of how debt can restrict veterinarians who need or want to do something other than full-time clinical work. She graduated about $150,000 in debt and will pay $800 monthly for 30 years on her current plan, she said.

When her husband, an officer in the U.S. Coast Guard, got stationed in Alaska, Anderson found herself in a town with narrow job opportunities at three clinics. She said she worked at two of them and was let go from both without notice.

At the first clinic, she was never put back on the schedule after she requested time off to have a baby. At the second, she was laid off when the clinic reduced its weekend hours. By that time, she was a mother of three.

“There was this sense of ‘Oh my gosh. I’m stuck here, and I have this debt to pay and I don’t know how I’m going to work,” she said. “If I had been the sole support, we would have had to move.”

There were a couple of saving graces: Her husband was financially stable and her youngest child was a year old at the time — old enough to allow her to travel to do relief work and continue making her payments. “Thank goodness it didn’t happen when I had a newborn,” she said.

She realizes not everyone is as fortunate. “I know vets who absolutely just feel trapped,” Anderson said. “They don’t like the profession, and they feel trapped by their debt, and they feel tricked.”

Photo by Warren Mattox

Tony Wynne, director of admissions and recruitment affairs for the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges, advocates considering campus location, culture and climate, as well as cost.

More than money

Not everyone believes that choosing a veterinary college should be so black-and-white.

Tony Wynne, director of admissions and recruitment affairs for the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges and director of the Veterinary Medical College Application Service, touts a holistic approach when he gives lectures and creates webinars for prospective students.

“Yes, cost is critical, and yes, cost is oftentimes prohibitive,” Wynne said. “But I would never condone going to the cheapest school just because it’s the cheapest school.”

He advises looking at a combination of location, the culture and climate of the school, and cost.

If an applicant is interested in equine medicine, for example, areas with large horse populations may offer more opportunity, and some schools boast more options for equine tracks and residencies. Wynne also believes campus culture — diversity, student satisfaction, learning environment — shouldn’t be ignored because it can have a significant effect on student wellness.

“If you go somewhere just to save money and you become terribly unhappy, it’s going to be a miserable four years,” Wynne said.

Dr. Megan Tremelling did just that. For cost reasons, she chose to attend her in-state school at the University of Wisconsin. But Tremelling said the program, which during her time there in the late 1990s focused largely on dairy and required many rotations on large animals, left her ill-prepared for the area in which she was truly interested: small animal emergency care.

“ ‘Miserable’ is not too strong a word to describe working 80 hours a week in the barn, doing mindlessly repetitive treatments on inpatients — not to mention freezing my backside off in the required apparel of coveralls and barn boots — when boards were coming up fast and I had no time to study for them,” she said.

By devoting all of her electives to small animal medicine, Tremelling said, she learned enough to go into practice. But for emergency medicine, she felt underprepared, especially in surgical skills. “I’m afraid I was a bit of a disappointment to my employer,” she said.

Tremelling learned on the job at her first emergency clinic. Now she works in Milwaukee in emergency and critical care, a field she’s been in for 16 years.

To this day, she wonders if a different school, perhaps one that had allowed more personalized education, would have been better for her.

“So many hours wasted in the barn that I will never get back,” she wrote in the VIN forum. “So much cool emergency room stuff that I never even knew existed until I was out and people expected me to already know how to do it! I have worked hard to correct those training deficits over the years, but will never feel like I am quite caught up.”

She added in an interview by email, “How much cheaper does a school have to be to make it worth going there, rather than the one that’s a good fit for you?”

But some advocates of choosing based solely on cost argue that while other issues can be worked around — students can seek outside experience if a school doesn’t offer a specialization, for example — burnout from debt is inescapable.

Photo Courtesy of Dr. Andrew Mackin

Dr. Andrew Mackin advocates selecting a veterinary college based on affordability. A professor and interim department head of clinical sciences at Mississippi State University College of Veterinary Medicine, Mackin observes that the more debt a student amasses, the narrower his or her career options become.

Mackin holds that other factors should come into play only if costs are comparable.

“No U.S. veterinary school is so good, or so bad, to justify that kind of tuition difference,” he said.

Wynne acknowledged that as long as the school is accredited by the AVMA, he believes students will get a quality education. He said he believes employers don’t typically care where a student went to school, and the AAVMC actively discourages students from getting hung up on rankings.

“They think they’ve gotta go to the number-one ranked school,” he said. “We say [whether] you go to Florida or Iowa or Cornell, you get the same education.”

Where to go, how to go

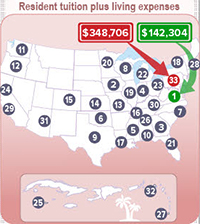

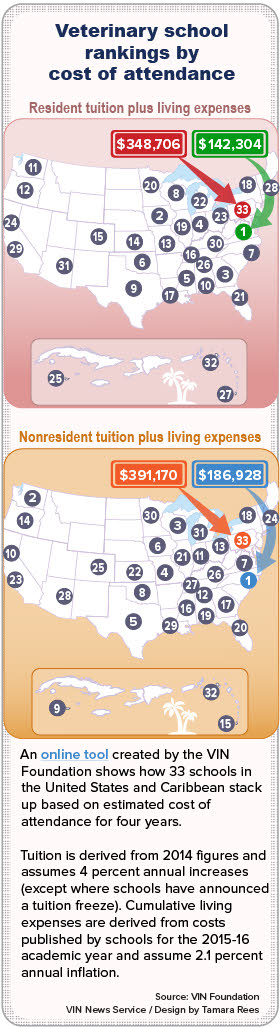

The cheapest option will often, but not always, be an applicant’s in-state school, because resident tuition, if available, typically is much lower than nonresident tuition. The VIN Foundation offers an online tool with which users can rank the cost of veterinary colleges based on their home state.

A few colleges allow students to establish residency after the first year and convert to in-state tuition, and many states without veterinary programs contract with colleges in other states to offer in-state tuition, all of which are factored into the tool.

Considering four-year cumulative cost including living expenses for 2015, the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine offers the lowest in-state price (available to residents of Virginia and Maryland) at $142,304, while North Carolina State University provides the cheapest option for out-of-state students at $186,928.

Students and prospective students employ a variety of creative techniques to save money. Some veterinarians said they have colleagues who deferred college for a couple years to move and establish residency in the state where they planned to attend school, or lived with their parents to reduce expenses. MSU offers an early-entry program in which students can do their undergraduate degree and be eligible for in-state rates by the time they reach veterinary school.

Students who end up with heavy student loans and incomes not up to the task may find relief in an income-driven repayment plan. Several programs are available to borrowers of federal education loans.

For Pangburn, the student headed to UC Davis, selecting a school was relatively easy. UC Davis is the highest-ranked school, her cheapest option among schools that accepted her, and her first choice. Even still, she will likely graduate with hefty debt. The four-year cumulative cost, including living expenses, for in-state students who entered the program in 2015 was $249,394. (Estimates for the class entering this fall aren't available yet.)

“It scares me to a certain extent, now that I’ve committed,” Pangburn said. “I’m a really optimistic person, and I would like to think I can be smart about my money and try to pay it off in a reasonable amount of time. I don’t know exactly how much my loans will turn out to be in the next few years or how it will affect my lifestyle. We’ll see how scared I am then.”

Although fortunate in many ways, Pangburn is nowhere near as lucky as Mackin. Her biggest disadvantage, perhaps, was not being born in a different place and time.

When Mackin graduated from veterinary school in Australia in the early 1980s, it was free.