Photo by Joyce Carol Oates

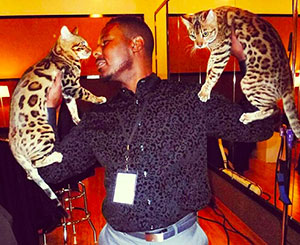

Anthony Hutcherson hoists Flowmaster (left) and Masterstroke during a Cats vs. Dogs contest at the 2014 New Yorker festival. Hutcherson joined the writer Joyce Carol Oates and others on Team Cat. (Dogs won.) A long-time breeder of Bengals, Hutcherson recently submitted a DNA sample from Flowmaster for research on the genetic basis of glittery fur.

When it comes to medical conditions caused by genetic defects, researcher Leslie Lyons would like to render the term “idiopathic” obsolete.

Ending the need to describe a disease as having an unknown cause is a top goal of a project Lyons is leading at the University of Missouri College of Veterinary Medicine. Dubbed 99 Lives, the project involves sequencing and studying the genomes of at least 99 domestic cats to identify the genetic mutations that cause health problems.

Along the way, Lyons and team are looking at unusual traits of all types — odd coat color, say, or curled ears — so their exploration is not limited to unhealthy cats. “We’re interested in the weird and the wacky,” Lyons said.

Healthy cats are candidates for study, too, as are wild cats. “Everybody helps,” said Lyons, who has a doctorate in human genetics and expertise in comparative medicine. “The cats that are healthy tell us where not to look in the genome [for mutations that cause disease].”

To recruit candidates, Lyons has put out a call to veterinarians and the public. Participating cats may be felines that have undiagnosed health conditions, cats with rare coat qualities, or ordinary pets whose owners simply would like to contribute to science.

“They can go to their vets and say, ‘I want to participate in this.’ Show them this article, and say, ‘Will you help me draw this blood sample and send it to Dr. Lyons?’ and we’ll get on the phone with the veterinarian and discuss everything,” Lyons said.

The cost of sequencing one cat’s genome is $2,000, plus another $1,000 for analysis. Owners who would like to submit their cats’ DNA aren’t obligated to pay that amount, but some do; others make a partial contribution. To make up the difference, Lyons' lab has been raising money through the 99 Lives website.

“Some people have just said, ‘Here, sequence my cat. Here’s the money.’ Others say, ‘I can contribute only 25 bucks,’ Lyons said. “That’s fine. As the money adds up [from donations], once we reach $2,000, we say, ‘Hey, who’s the cat at the top of our priority list?’ ”

Since the project began in fall 2013, the lab has obtained DNA samples from 74 domestic cats and nine wild felids, including tigers and lions. So the researchers are close to their goal of 99 participants, but they won’t stop there. “It’s not like we want to end at 99,” Lyons said. “We just gave ourselves a goal.”

Some early results: “We have sequenced cats, Persians and Bengals, that had two different inherited blindnesses, and we’ve been able to find those conditions,” Lyons reported. “We’ve sequenced a Devon Rex with a condition, spasticity, known as congenital myasthenic syndrome in people. We’ve discovered a lymphoproliferative disease, kind of like a cancer, in British shorthairs.”

Genome analysis offers a potential option for veterinarians whose patients have conditions that confound other diagnostics, Lyons said. “We might be able to help that particular cat. Maybe not,” she added, “but at least we can advance the science.”

For example, Lyons said her lab received a call recently from Auburn University about a cat with a neurological disease that resembles a neurological disease seen in dogs. “Can you test the gene?” the caller asked.

“We said it was very unlikely that it would have the same DNA mutation as the dog,” Lyons recounted. “So we have an undiagnosed neurological condition. We can add this cat to the list.”

Lyons said the first goal is to assist with diagnosis. The next step: “Can we use that [information] to give a cat precision medicine, medicine designed for its genetic makeup?”

Just as that approach is becoming state-of-the-art in health care for people, so Lyons would like to see it available for cats. She said, “We want to bring them state-of-the-art, precision health care.”

In conditions found to be associated with a particular breed or breeds, the genetic information can be used to help eradicate the condition from the breed, she added.

Beyond researching the genetics of disease, the project has a lighthearted side.

Among healthy cats in the study, one is a 2-year-old male Bengal named Flowmaster. His owner, Anthony Hutcherson, has been fascinated with exotic, wild-looking domestic cats since he was in high school. “I always wanted a cat that looked like a leopard,” he said.

Now a breeder, Hutcherson frequents genetics conferences. It was at one such conference recently that Hutcherson listened to a speaker criticize breeders for focusing on physical traits, often to the detriment of temperament.

Hutcherson spoke up, countering that breeders do pay attention to temperament and behavior, even if breed standards don’t explicitly recognize personality traits.

“I’ve been a Bengal breeder for 23 years. I don’t want to breed any cats that are mean, because mean cats make mean kittens,” Hutcherson told the VIN News Service. “Nobody wants to deal with a cat that is mean. You want them to look as wild as possible but behave in the exact opposite way. That’s something we select for ... before anything else.”

Another scientist, Dr. Sam Boutin, a veterinarian with a doctorate in molecular and systems bacterial pathogenesis, heard Hutcherson at the conference and was impressed. “Wow, you’re really into this,” he said.

Boutin urged Hutcherson to pick out his sweetest, friendliest and wildest-looking cat, and offered to pay for its genome analysis.

That’s how Flowmaster became one of Lyons’ 99. “He was just rolling over my feet this morning,” Hutcherson said in a telephone interview. “He’s got his first kittens on the ground. They are 4 months old. You just touch them and they roll over. They are very loving cats.”

As beguiling as it sounds to identify the genetics of temperament, though, Lyons said she can’t do it.

“Sweetness — how do you categorize that?” she said. “It would be very complex, too, and need more than one [cat].”

So Flowmaster’s DNA will be put to another purpose: identifying the genetics of a type of coat coloration known as glitter. As the name suggests, glitter imparts an iridescent sheen.

Some things are known about glitter coats. The trait traces back to a street cat from India imported to the United States in 1982 by Jean S. Mill, founder of the Bengal breed, according to Hutcherson, who considers Mill his mentor. Look at a glittered Bengal’s fur under the microscope and you can see air bubbles in the hair shaft that refract light, he said.

But the gene or genes that govern glitter? Unknown. “Dr. Lyons will be the first to pinpoint it,” Hutcherson predicted.

Reached by email, Boutin, a consultant, said he hopes genetic and biomarker studies related to pet behavior will be done in the future. He hopes, as well, that individual genome analysis becomes routine for pets.

“I would love to see the cost of genome sequencing drop to the point where it is standard operating procedure to collect it for every veterinary patient,” Boutin said.