Photos courtesy of the University of California, Davis School of Veterinary Medicine

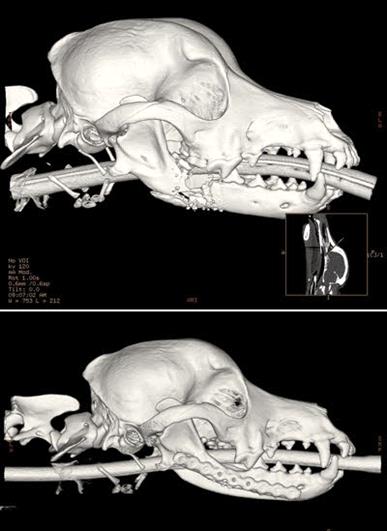

These CT scans feature Frankie, a dog who sustained a gunshot that shattered a large section of his right mandible. Surgeons at UC Davis removed the loose bone fragments and screwed a titanium plate into the remaining bone. A sponge-like chunk of scaffolding material soaked in bone morphogenetic protein, a bone stimulator, was inserted into the space where the bone was removed. That stimulated Frankie's remaining jaw bone to grow new bone cells, eventually filling in the defect and integrating with the native bone.

The preoperative CT scan (top) shows the extent of damage to the jaw while the postoperative CT scan (bottom) shows the new bone growth several months after surgery.

Like most of his colleagues, Dr. Frank Verstraete used to tell owners that their dogs would adapt following a mandibulectomy, a procedure to remove diseased or injured parts of the lower jawbone.

“Your dog will be fine, his jaw will be skewed, but he’ll cope,” the oral surgeon would say, describing how soft tissue would fill in over the missing bone. Until recently, that was the best option for dogs with severe jaw defects.

Nowadays, Verstraete and fellow veterinarian Dr. Boaz Arzi, both on faculty

at the University of California, Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, offer another option for some patients — an attempt to regrow the bone to replace what's excised surgically.

The oral surgeons use an orthopedic plate to bridge the gap in the bone and a compound called bone morphogenetic protein, or BMP, to encourage new bone growth and fill the void.

Twenty or so dogs have been successfully treated since 2011. The technique appears to be the first of its kind.

“Until our work, when people did a mandibulectomy they would just leave the defect," Verstraete said. "Dogs did OK, but not great because they developed malocclusion."

The veterinarians' collaboration began in 2010, when Arzi learned of the novel materials used in bone regrowth and fusion in human medicine as part of his postdoctoral work in UC Davis' biomedical engineering department. He and Verstraete brainstormed with engineers and surgeons from the medical school to design the orthopedic plate and figure out the proper dose of BMP, the bone stimulant.

BMP works by stimulating osteoblasts, the cells that produce new bone. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved its use in human medicine for spinal fusion and some dental work. Verstraete stressed that the technique for jaw reconstruction is novel "so the company and the medical people are very interested in what we are doing because it may contribute to FDA approval.”

The protein, while expensive for its labeled usages in human medicine, is available only on a trial basis for canine jaw reconstruction,

Verstraete explained. Patients must be screened for eligibility to reduce the potential for adverse health effects. The procedure currently costs $7,000 to $8,000, though that cost is likely to vary substantially if BMP enters mainstream use for this procedure.

A potential side-effect of BMP, a protein specifically formulated to stimulate bone growth, would be inadvertent stimulation of the growth of cancer cells in an area where there was once a bone-producing tumor. “The concern would be bone tumors, that you stimulate osteoblasts too much," he said.

That has yet to happen in dogs that have undergone the procedure. Even so, BMP is a potent molecule that should not be used cavalierly, Verstraete said.

“We have only used it in epithelial tumors, and ones that we’ve excised completely," he said. "So the question is: What if you used it in mesenchymal tumors, especially if you leave cancer cells behind?”

Epithelial tumors form from tissues that line cavities and surfaces of structures throughout the body; mesenchymal tumors develop from tissues of the lymphatic and circulatory systems, as well as connective tissues throughout the body such as bone and cartilage.

Verstraete explained that the technique has been performed in three types of cases: segmental mandibulectomies, in which a section of one side of the lower jaw is removed; bilateral rostral mandibulectomies, in which bone that spans the front arch of the lower jaw, encompassing parts of both mandibles, is removed; and fractures that don’t heal by conventional means, usually in small dogs that have had bone compromised due to severe periodontal disease.

Next phaseThe veterinarians and their colleagues recently have taken their technique a step further, using a 3D printer to produce models of the skull from the CT scans.

The model skulls save surgical time and allow for better planning of the surgery. “With the bilateral rostral mandibulectomies, because it takes a lot of time to bend the plate, we bend it on the model (prior to the surgery). That saves us a lot of surgery time,” said Verstraete, noting that the team also has put the models to other uses.

“We use it in teaching and also in client education — very useful, very very useful," he said. "The 3D model is almost a rehearsal."

While the bone regrowth procedures performed thus far have had favorable outcomes, they have been limited to lower jaws in dogs. Verstraete discussed the possibility of expanding the procedure to other species or other areas of the body, acknowledging potential challenges.

“We haven’t done any upper jaw reconstructions,” he said, explaining that the upper jaw connects to sinuses and the nose, a more complicated region.

"We haven’t done cats yet," he added. "Non-healing fractures are rare in the cat, and tumors are usually more extensive.”

Use of the technique in certain orthopedic surgeries might be on the horizon. Verstraete believes it could repair limb fractures, particularly those where the bone fails to knit properly with normal immobilization.

“Long bones are different in the sense that they’re weight bearing," he said. "The mandible is load bearing but not weight bearing. But we’ve started working with non-healing fractures.”

Veterinary surgeons at Cornell University trained at UC Davis to do the procedure, but so far, they are not performing reconstruction and regrowth techniques, Verstraete said. Whether the technique will move beyond UC Davis and become mainstream is unclear.

Verstraete suspects that will depend on the retail price of BMP. Right now, it's expensive, he said.