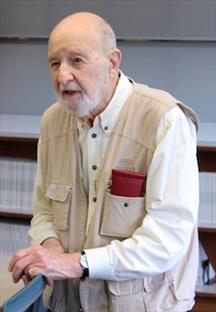

Photo by Karin Kandur

Former dean and academician Dr. Robert Marshak met last month with members of the New Jersey Veterinary Medical Association, asking that they lobby the federal government to crack down on accreditation practices of the Council on Education.

Practitioners gathered last month at Red Bank Veterinary Hospital in New Jersey to hear concerns about how the American Veterinary Medical Association Council on Education (AVMA COE) accredits veterinary medical colleges, including those on foreign soil.

Longtime COE critic Dr. Robert Marshak, professor emeritus of the University of Pennsylvania’s veterinary school, led the discussion. AVMA leaders attended the meeting by phone in the accreditation program’s defense.

Debate concerning how and where the COE accredits veterinary medical colleges is heating up in anticipation of the evaluating body’s re-review this December before the U.S. Department of Education’s National Advisory Committee for Institutional Quality and Integrity (USDE NACIQI).

The COE is the AVMA’s accreditation arm, comprised of 20 or so volunteers, most of whom are veterinarians. The body was tapped by USDE in the 1950s to evaluate U.S. veterinary education but does not oversee its international accreditation efforts. Rather, the AVMA's leadership initiated and drives the COE's evaluations of schools outside of U.S. borders.

NACIQI reconsiders the COE's appointment every five years and soon will again, having ordered the group to improve transparency, weed out conflicts of interest and rework policies, procedures and standards so they’re uniformly applied and less confusing. Those edicts and others were handed down in December 2012, after veterinarians critical of how the COE functions testified before NACIQI, accusing the accrediting body of being overly influenced by AVMA politics and operating outside of federal guidelines and directives.

AVMA officials now say they’ve done all that NACIQI asks, outlining ways in which the COE has changed in an eight-page response to the agency. Regarding NACIQI's order to function with less ambiguity, for example, the AVMA noted several modifications:

“All accreditation decisions, positive and negative (whenever they occur), are now posted on the AVMA website in direct association with the specific decision meeting. Negative decisions are not posted until the due process and appeal process are completed and the decision becomes final.”

Critics argue that the modifications aren't enough to convince them that the COE operates openly and independently of the AVMA's political influence, with the autonomy that federal regulations require of accrediting agencies. The argument underscores a massive philosophical divide within the veterinary profession, pitting AVMA leaders who support the COE's foray into international accreditation against those who say evaluators should sharpen their focus on domestic programs.

Across the country, veterinary colleges are imposing tuitions so high that most graduates are entering the workforce $160,000 or more in debt. Academicians say increases are needed due to cuts in funding from state legislatures.

For these reasons, Marshak and others want NACIQI to suspend the COE’s recognition as the nation’s sole accreditor of veterinary education. It’s the latest in a four-year battle to compel the AVMA to cease foreign accreditation, loosen ties with the COE and tighten standards that permit programs to forgo teaching hospitals in exchange for distributed learning.

AVMA COE Dr. Ron DeHaven welcomes the debate, which he considers to be "old as the AVMA and vital to keeping the association strong."

"It is my hope that each side will listen to the other with respect for their colleagues and tolerance for differences of opinion," he said by email. "Ultimately I am confident that the course of action taken will be what is best for our profession."

That would involve upending how the COE operates, Marshak said. In a letter to state veterinary medical associations across the country, he's asked stakeholders to lobby NACIQI to insist that the COE rigorously abide by its standards when assessing veterinary education — or face suspension.

"This is essential if we are to ensure that veterinary medicine remains a economically viable and science-based profession retaining the respect of fellow health professions, agriculture and the public," Marshak wrote, recognizing the COE's influence on the "nature and quality of veterinary medical education."

“Whenever published standards are weakened, ignored, applied loosely and inconsistently, or are subject to manipulation by political, commercial or other interests, educational quality, the profession and the public we serve are bound to suffer grievous harm,” he added.

Marshak contends that the pathway to U.S. accreditation isn’t paved with serious scrutiny. Rather, he said the COE operates in a defensive manner to stave off lawsuits such as the one filed by Western University of Health Sciences (WesternU) in 2001, which was the nation's first to skip the expense of building a teaching hospital in which to train students and instead rotate them through private practices.

For years, the COE pushed back on the idea that the distributed learning model could replace traditional teaching hospitals — a stance that spurred WesternU to legal action. The lawsuit was dropped when the COE green-lighted the veterinary college nine years later.

Since then, other veterinary programs without teaching hospitals have opened with the COE's blessing.

“It now seems clearly evident that once a new school submits a self-study document, receives a COE site visit and is granted reasonable assurance, it is virtually certain to achieve full accreditation,” Marshak said in his letter.

Going global

Veterinary accreditation hasn’t always been fraught with tension. During the first several decades of its existence, the COE operated amid little fanfare.

It wasn’t until the mid-1990s that AVMA officials resolved to take COE accreditation overseas in an effort to elevate veterinary education internationally. Since then, a surge in overseas approvals has raised eyebrows within the AVMA’s 85,000-plus membership. All but one of the AVMA-accredited foreign programs have earned the distinction since 1998.

Critics point out that for the most part, the COE has only accredited top-notch schools that other respected evaluators already have accredited. The Royal Veterinary College at the University of London, for example, is accredited by the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, European Association of Establishments for Veterinary Education and the Australasian Veterinary Board Council, in addition to the AVMA COE.

Some wonder whether the AVMA’s self-imposed mission to spread U.S. accreditation internationally is more about the group's status as a global leader than "raising the bar" in veterinary education. Concerns also exist that the United States is becoming saturated with veterinarians due to a proliferation of domestic veterinary schools and growing numbers of accredited foreign programs that cater to American students.

AVMA officials repeatedly have stated that workforce issues should play no role in how the COE operates or whether international accreditation continues. Doing otherwise might spur litigation or invite scrutiny from the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC), AVMA attorney Isham Jones has advised.

Legal experts outside of AVMA offices say that's unlikely. According to legal opinion solicited by the Veterinary Information Network (VIN), parent of the VIN News Service, "non-import commerce" that does not have a direct, substantial and reasonably foreseeable anticompetitive effect in the United States was excluded in 1982 from the Sherman Antitrust Act jurisdiction.

News in the July 15 issue of the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association states otherwise, warning that "FTC says it's watching accreditation activities." The story implies that the veterinary profession — and calls for the COE to end overseas accreditation — could attract the agency's scrutiny.

Critics say that's a scare tactic. The FTC article on which the JAVMA story is based never mentions the veterinary profession or trade issues involving international business. It gives as examples a trade group's ban on music professionals soliciting each others' clients and an association of flag manufacturers that attempts to get its members to raise prices.

"The JAVMA story is a complete distortion of what the FTC is actually saying," said Raphael Moore, VIN's legal counsel. "No one has ever argued that associations are not subject to antitrust scrutiny. But the cases they cite deal with associations restricting their own member behavior toward fellow members (e.g., preventing members from offering discounted rates to another member's clients).

"None of that is relevant here," he continued. "The issue with AVMA is very distinct and involves restricting foreign veterinarians, when they already have other ways of entry into the United States market. Even if deemed anticompetitive, such action is excluded from the reach of the Sherman Act."

Whether real or imagined, potential antitrust threats aren't driving all opinions. Many believe the COE's overseas reach is constructive for altruistic reasons.

“There’s no question that through the accreditation of foreign schools, the AVMA has had a positive influence on the standards of veterinary education throughout the world,” said Dr. Link Welborn, an AVMA delegate representing the American Animal Hospital Association. “We should take pride in that.”

Welborn's statement came during the AVMA's biannual meeting last January in Chicago, where the AVMA House of Delegates gathered to debate several resolutions, one of which was a bid to end foreign accreditation.

Like others before it, the resolution failed to pass the House, the AVMA's policymaking body. And when the group meets this week in Denver, another accreditation resolution is unlikely to make the agenda.

That doesn't mean delegates won't be talking. Adding fresh momentum to the cause to rein in accreditation is news that the COE recently ousted one of its own, Dr. Mary Beth Leininger, after she publicly expressed concerns that the volunteer body is overextending itself to accredit international programs — a mission that the AVMA initiated on its own, with no USDE guidance or directive.

“We’re using our volunteer resources ... frittering them away by giving them to the foreign schools," Leininger told delegates in January.

Five of 12 programs assessed by the COE this year are based on foreign soil. In June, the COE conducted a consultative site at Seoul National University in South Korea. Oniris National College of Veterinary Medicine in France is scheduled for a COE visit in November.

“I believe the educational process in the United States is so troubled right now that unless a body that has clout with schools starts addressing some of the problems … we'll be in trouble,” she added.

Leininger, named the AVMA’s first female president in 1996, plans to appeal her dismissal with the AVMA Board of Governors. Until there’s a final outcome, she’s refused to talk about the ordeal.

So has the AVMA.

"Regarding Dr. Leininger's situation, I clearly cannot comment since this is an ongoing personnel issue that is following an established internal process," DeHaven said by email.

In writing

What he can talk about are the COE's merits. Last month, DeHaven sent a three-page letter to every state veterinary medical association in the country, defending the status quo.

“The AVMA COE goes to great lengths to ensure the quality of its accreditation process beyond the stringent requirements of USDE,” he wrote. “The USDE only recognizes accrediting bodies that follow their strict operational guidelines. Through this process, the COE must demonstrate that accreditation decisions are independent of the AVMA …”

Dehaven also has exchanged emails with Marshak, trading jabs amid defense of their perspectives. The Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges also has gotten involved, with Executive Director Dr. Andrew Maccabe joining the letter-writing efforts on the AVMA's behalf.

The correspondence has been widely distributed, copied to dozens of stakeholders throughout the profession.

Back at Red Bank, the New Jersey Veterinary Medical Association’s (NJVMA) leadership weighed whether to write to NACIQI members, asking that they forgo support of the COE program. Executive Director Rick Alampi said the group “recognizes this as an issue of great importance to the profession.”

When asked whether the NJVMA would join Marshak's call to lobby, he stated, “We want to make an informed decision.”

Valerie Fenstermaker, head of the California Veterinary Medical Association, said much of the same: “We’re looking at this pretty closely.”

The Pennsylvania Veterinary Medical Association (PVMA) is on board, distributing letters on Marshak’s behalf that urge others to join their efforts.

"State veterinary medical associations are in a powerful position to influence NACIQI to recommend withholding recognition of the COE pending the adoption of a restructured and wholly autonomous COE," PVMA Executive Director Charlene Wandzilak wrote. "The opportunity to weigh in only comes once every five years so it is incredibly important to take advantage of the written comment period."