Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

Five years into her career as a veterinary internal medicine specialist, Dr. Lori Rios could have been feeling at the top of her game. And for the most part, she was. But there was one big hitch.

Rios' job was located 120 miles from her home in Central Virginia. For three years, she rented an apartment in Roanoke, returning on weekends to the house she owned with her husband.

The problem wasn't that Central Virginia didn't have jobs for veterinary internists. There were three specialty hospitals in nearby Richmond. However, while working at one of those practices, Rios signed an agreement that prevented her from taking another position anywhere within 25 miles for three years after leaving. The closest specialty practices outside that radius were in Washington, D.C., or Roanoke, each more than 100 miles away.

At the time she accepted that first job, in 2008, all of the specialty clinics in the area had strict noncompete provisions, Rios recalled. Had she refused to sign, she said, "I don't think I would have had a job."

When she decided to move on after five years, she faced several disagreeable options: She could pay her employer one year's salary to escape the noncompete obligation; do something other than practice medicine for three years; or find a veterinary position outside the radius circumscribed by the noncompete.

Reluctantly, Rios chose the third option. "I missed three years of family life due to the noncompete," she said. "This is a steep price to pay to be an associate."

Rios spoke to the VIN News Service about her experience because she hopes like-minded colleagues will voice their support for a proposal that could help other veterinarians avoid the same dilemma.

The Federal Trade Commission in January proposed banning employers from imposing noncompete agreements on their workers and requiring employers to rescind existing noncompete clauses. The proposal applies to employees only; it does not address noncompetes related to the sale of a business. The public comment period is open through March 20.

As the name indicates, noncompetes are legal agreements designed to stop employees from competing with employers once employment ends — usually by restricting the employee's right to work within a certain radius around the employer's business for a period of time.

The FTC describes the use of noncompete agreements as "a widespread and often exploitive practice that suppresses wages, hampers innovation, and blocks entrepreneurs from starting new businesses."

Noncompete agreements are hotly debated in the veterinary profession, judging from multiple recent message board conversations on the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of VIN News.

Associates have posted about how the clauses trapped them in toxic work situations and hampered their ability to advocate for better pay and workplace improvements. Others say noncompetes are exacerbating veterinarian shortages by keeping practitioners out of the market.

There are also voices in support of noncompetes. Some independent practice owners, for example, argue that these agreements are essential for protecting their investment. They say without them, associates can quit, go to a competing practice the next day and take clients with them.

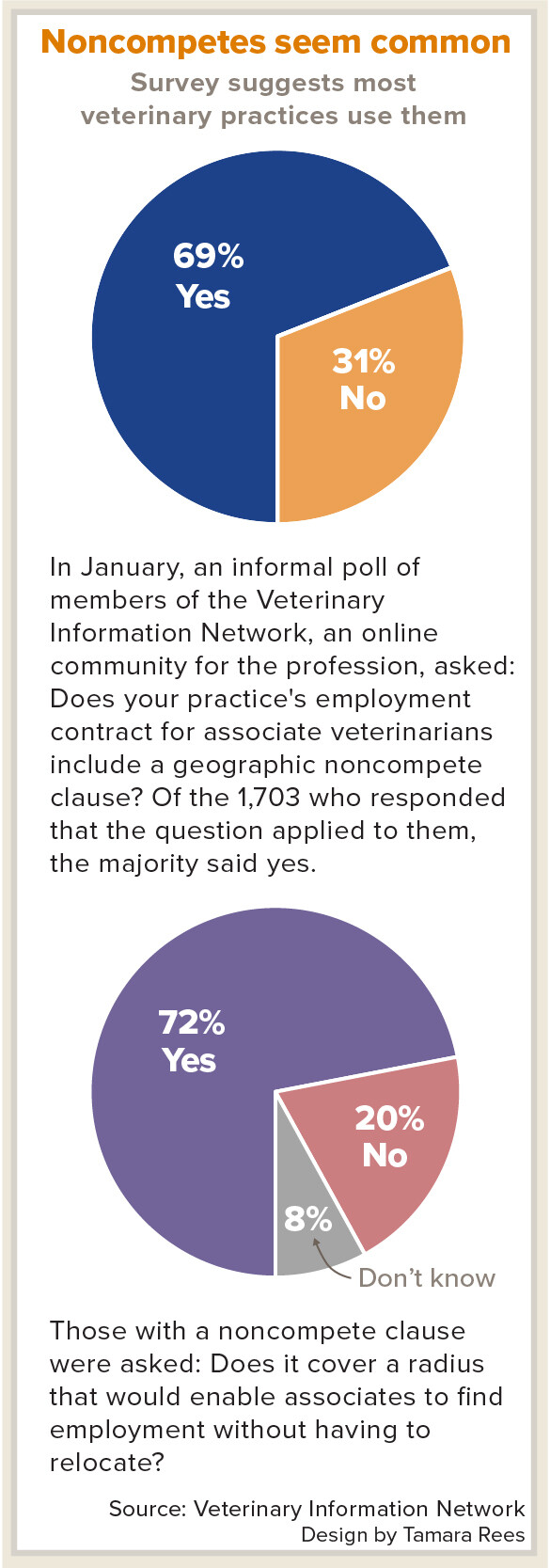

No firm numbers exist on the proportion of practices that use noncompetes. Generally, it is believed they are more common at specialty and emergency hospitals.

A poll of VIN members in January asked veterinarians if their practice had noncompete agreements for associates. Of the 1,703 who responded that the question applied to them, 69% worked at a practice that required noncompetes, while 31% did not. (For some respondents, the question wasn't applicable to them because they were the sole veterinarian in a practice or worked relief, for example.)

The big picture

In some form or other, noncompetes have been around for a long time. They existed in English common law all the way back to the 1400s, according to VIN General Counsel Raphael Moore.

In modern times in the United States, the agreements traditionally have been used for white collar professionals likely to have access to company intellectual property. However, tight labor markets have reportedly driven up the use of agreements for blue collar workers of all types.

The FTC says that one out of five American workers, or about 30 million people, are bound by a noncompete.

In an opinion piece published by the New York Times in January, FTC Chair Lina Kahn wrote: "In theory, noncompete clauses promote investment and innovation by assuring companies that their employees can't run off with valuable secrets. But the reality looks very different."

The FTC argues that nondisclosure agreements and trade secret law are better tools for companies looking to protect proprietary information.

Noncompetes already are banned in California, North Dakota and Oklahoma. A number of other states — among them, Colorado, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, New Hampshire, Oregon, Rhode Island, Virginia and Washington — have restricted noncompetes to higher-salaried positions.

Massachusetts began in 2018 capping time in a noncompete to one year and prohibiting employers from enforcing the agreements against employees who have been fired or laid off. In addition, Massachusetts bans noncompetes for physicians, nurses, psychologists and social workers. A bill introduced in the Massachusetts senate this year would add veterinarians to the list.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce attacked the FTC proposal, calling it "blatantly unlawful." The American Veterinary Medical Association has no position on noncompete agreements, although AVMA spokesperson Mark Rosati recently told VIN News the organization is "looking into the issue."

Veterinarian views

In a VIN message board discussion about the FTC proposal, the majority of posters expressed support for a ban on noncompetes. (VIN message board discussions are confidential; the posters quoted agreed to making their comments public.)

"[Y]ou can make a decent argument that noncompetes are against [the] public interest, especially in veterinary medicine," wrote Dr. William Thomas, a professor of neurology at the University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine and interim hospital director. "By preventing a former associate from working in the region, it restricts the ability of clients to choose their veterinarian."

Thomas also pointed out that when associates can't easily switch jobs, hiring at new or growing practices is more difficult. "Veterinarians are prevented from making optimal use of their talents," he said. "By stifling competition, it benefits the former employer at the expense of economic health of the entire industry."

A noncompete also takes away an employee's "ultimate bargaining chip" — leaving the job, Thomas said.

With a noncompete, "the associate is less empowered to negotiate for higher salaries, other benefits, or changes in practice policy because it may not be economically feasible for the employee to leave," Thomas wrote. "Veterinarians can be forced to continue to work at a job that is no longer a good fit or even worse, in a toxic environment at considerable risk to the employee's mental health."

Dr. Alex McFarland, an associate veterinarian focusing on avian and exotic pets at an emergency and specialty hospital in Grand Rapids, Michigan, said some veterinary clinics realized that a noncompete could keep an employee from quitting and took advantage of it.

"The thing about noncompetes is they're not meant to be used the way this profession is doing it, and [that's] exactly why the FTC is cracking down," he wrote. "It's supposed to protect trade secrets or sensitive information, not prevent someone from going across town and 'taking away business.' "

He added: "If someone wants to leave a clinic for whatever reason, they should be able to pack up and leave. If … clients, without being asked, go to the new practice, then that is the problem of the clinic."

Dr. Chiara Switzer, a part-time small animal veterinarian in Toronto, put it more colorfully. "If an owner can't maintain their business without controlling ex-employees … something's wrong," she wrote." It's trying to kill a fly with a sledgehammer."

In 2021, Switzer's home province of Ontario became the first and so far only Canadian province to ban noncompetes.

Some who oppose noncompetes believe legislation or regulation is not the appropriate remedy. They argue that the tight labor market enables associates to refuse to sign onerous agreements.

Those faced with noncompetes, however, say this is hard to do when all the employers in a given area require them.

According to the FTC, the majority of job seekers feel forced to accept the agreements. "Only a small percentage of workers actually bargain over noncompete clauses," Kahn wrote in her essay. "In fact, employers often spring them on workers after they've accepted a job, when their bargaining power is effectively zero."

Expecting associates to turn the tide on noncompete agreements by refusing to sign is too much to ask, and unlikely to succeed, believes Dr. Megan Tremelling, an emergency practitioner in the Milwaukee area.

"One worker cannot change working conditions by demanding safe working conditions, a fair contract, etc., as long as they can be fired and replaced," Tremelling wrote on the VIN message board. "It only works if they all do it at once or if it is legislated. It is very difficult to get any number of people to all dig their heels in at the same spot at the same time. All you need is a few people to cave, and you're sunk."

Is there a place for 'reasonable' noncompetes?

Dr. Joe Waldman, who owns a clinic in Calgary, Alberta, has used noncompetes over the years for three associates, none of whom balked at the restrictions, he said. The terms were 6 kilometers (3.7 miles) for one year in a city of 825 square kilometers (513 square miles).

Waldman calculated the geographic restriction based on the distance, as shown on Google Maps, to the farthest clinic that drew clients from his same neighborhood. "At the time, there would have been about 50 to 60 clinics outside of that restriction zone," he told VIN News by email. Waldman currently has no associates under contract.

"The problem is that noncompetes are being used as a professional handcuff," he said. "Nobody should ever feel stuck working in a bad job. My 6-kilometer restriction was intended to protect my interest, but it would have had a nearly insignificant effect on an associate looking to move on."

Waldman said that in some instances, noncompetes can benefit prospective employees. For example, they may help employers feel more comfortable hiring inexperienced veterinarians with gaps in their training. "Mentorship comes with a big price tag, and there's no guarantee you're going to see a return on that investment," he said. "There's an element of financial risk when you hire an inexperienced veterinarian. The noncompete can be used as a way to balance that risk, but only where the parameters are reasonable."

Dr. Bruce Henderson, a hospital director at a New Jersey practice that uses noncompetes, said, "I have never had an associate, or potential associate, ask about the noncompete clause," he told VIN News in an email. "I take this to mean it really does not matter to them."

Henderson said he has but one reason for requiring the restriction: "I do not want them to open up a hospital two blocks away from me," he said. "This will hurt my business."

He considers the terms of his noncompete to be reasonable. "It would be about a 15-minute drive from the hospital," he said. "This would accomplish my goal of preventing an associate from opening a business across the street from me. It would also allow the associate to find another job without having to move or make major life changes."

Hospital chains: Some mum, others vocal on the topic

Noncompetes at large hospital groups are more likely to cross the line of reasonableness, according to several people who have seen or been bound by such contracts. In some cases, the noncompete radius is applied to all practices owned by the consolidator. With some consolidators owning hundreds, if not more than a thousand, practices, that restriction can lock out former employees from finding jobs across the country.

Large companies with deep pockets also potentially pose a more intimidating foe for a veterinarian who might want to challenge the terms of a noncompete.

VIN News repeatedly called and/or emailed a dozen medium- to large-sized corporate consolidators to learn whether they use noncompetes for associates and to request their view on the FTC's proposed ban. AmeriVet, National Veterinary Associates, VetCor and Mars — which owns the chains Banfield Pet Hospital, BluePearl Pet Hospital and VCA Animal Hospitals — declined to talk with VIN News about noncompetes.

Blue River PetCare, PetVet Care Centers, Thrive Pet Healthcare and Veritas Veterinary Partners did not respond to multiple messages.

David_Bessler

Photo by Benjamin Muir Bessler

Dr. David Bessler, CEO of Veterinary Emergency Group, expressed his opinion of noncompete agreements in New York City's Times Square in August 2021.

Meanwhile, one practice group that doesn't use the restrictive agreements is outspoken. A public relations company contacted VIN News in January to tout Veterinary Emergency Group's no-noncompete policy. Established in 2014, VEG owns 40 emergency hospitals in 14 states.

Its CEO, Dr. David Bessler, said in an interview that his company did use noncompete agreements in its early days because that was the industry default.

"Then, as we started hiring more doctors … we really looked at this whole noncompete thing," he said. "The main reason we got rid of it is because it didn't do anything for us; it was a blemish in our offer letter."

Bessler offered the example of a veterinarian with hefty student loans who takes a job in good faith and puts down roots. "Then they're like, 'You know what, I don't like my employer. I want to go work somewhere else,' " he said. "And guess what? They can't. They literally have to sell their house, move their kids to a different school … in order to stay in their profession. That's just so unethical and crazy."

When VEG announced in September 2021 that it would stop using noncompetes, staff veterinarians were distrustful. "They were trying to understand like, 'Where's the catch? What are you trying to do?' " Bessler said with a laugh.

Veterinarians at VEG are required to sign a "business protection agreement," the CEO said, which he described as covering really "egregious" things, like using VEG's approach and marketing. "You can't open a place called VEG next door to us. But people can open up their own emergency places right next to us."

Another company that sees its no-noncompete policy as worth promoting is Petco, which operates more than 200 hospitals in its retail stores under the brand Vetco Total Care. In early January, Petco sent emails to some veterinarians with the message:

"You may have seen the topic of noncompete contracts popping up in the news lately. We wanted to remind you that Vetco Total Care never requires noncompete contracts from applicants we hire and we never have.

"You deserve the freedom to take your career in any direction you choose, without limits."

After the noncompete expired for Rios, the internist in Virginia, she returned to working closer to home. But leery of noncompetes, which are still required by local clinics, she hasn't returned to full-time practice.

"I work as a relief veterinarian at this point, because … I don't want to be locked in where I don't have any opportunity to work anywhere else," she said.