Notable treatments target pancreatitis in dogs, diabetes in cats, osteoarthritis in horses

vns_pancreas_canine

Art by Tamara Rees

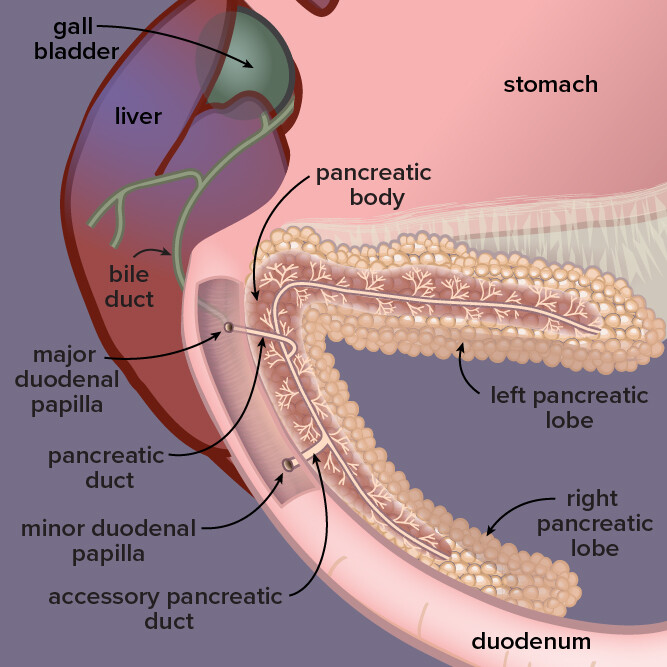

Located by the stomach and liver in dogs, the pancreas is a gland that secretes digestive enzymes and fluids as well as hormones that regulate blood sugar. In pancreatitis, or inflammation of the pancreas, digestive enzymes attack the pancreas itself.

Veterinarians in the United States are entering 2023 with three noteworthy new drugs in the tool chest, courtesy of recent regulatory nods.

For the first time, veterinarians will be able to access a drug that directly treats pancreatitis in dogs, now that a novel medicine developed in Japan has gained provisional approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

In addition, the regulator has approved the first orally administered medication for treating diabetes mellitus in cats, removing the need for insulin injections in some — though not all — patients.

Horses suffering from osteoarthritis, meanwhile, now have access to the first FDA-approved pentosan injection to control lameness.

Each drug comes with idiosyncrasies, and one with substantial risks: The drug for diabetes mellitus in cats comes with a black box warning about the potential for a fatal side effect.

Here is a lowdown on the three medications, each of which will reach the market later this year.

An injection for treating canine pancreatitis

Pancreatitis, an inflammation of an abdominal organ that produces digestive enzymes and hormones such as insulin, is fairly common in dogs.

Yet treatment options until recently have been limited to supportive care encompassing the administration of painkillers, fluids, anti-vomiting agents and a low-fat diet.

Now, an injectable product, branded Panoquell-CA1, can directly combat clinical signs of acute onset pancreatitis while dogs are hospitalized, the FDA says.

The disease involves the premature activation of digestive enzymes while they still are in the pancreas, causing the organ to digest itself. Risk factors include obesity, having diabetes, unusual or high-fat diets and exposure to toxicants such as zinc.

Clinical signs include dehydration, anorexia, vomiting, abdominal pain and lethargy. Fever, collapse and death can occur with severe acute pancreatitis.

Panoquell-CA1's active ingredient, fuzapladib sodium, blocks certain molecules on the surface of inflammatory cells, thereby preventing them from adhering to cells in the pancreas.

Fuzapladib sodium has been approved in Japan since 2018 for use in dogs, sold under the brand name Brenda Z. The same company behind that product, Ishihara Sangyo Kaisha, has developed Panoquell-CA1 for the U.S. market.

By granting conditional approval, the FDA has deemed the treatment to be safe, with a "reasonable expectation" of effectiveness. Conditional approval is valid for one year, with the potential for four annual renewals, during which time the developer must provide substantial evidence of effectiveness to achieve full approval.

A clinical trial conducted in the U.S. to test efficacy found that of 36 dogs afflicted with acute pancreatitis, 17 treated with fuzapladib sodium had a statistically significant reduction in clinical signs compared with 19 control dogs, according to a Freedom of Information Summary posted by the FDA. A separate safety study conducted on 32 beagles concluded that fuzapladib sodium did not produce systemic toxicity and had an "acceptable margin" of safety.

Still, the FDA said veterinarians should advise owners about possible side effects, including loss of appetite, digestive tract disorders, respiratory tract disorders, liver disease and jaundice.

Dr. Sherri Wilson, a canine internal medicine and endocrinology consultant for the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of VIN News, is cautiously upbeat, noting that veterinarians to date have been limited to providing supportive care.

In an interview, she said the drug's mode of action implies it will work better the sooner it is administered. Consequently, an initial challenge for veterinarians might be how quickly they can diagnose a severe bout of the disease.

Clues that could point to severe pancreatitis are signs of shock, low platelets, prolonged clotting times and low blood glucose. "But we could definitely use more markers that would help us predict severity," Wilson said.

The veterinarian cautioned that bigger studies will be needed to fully determine the drug's effectiveness. In the pilot study cited by the FDA, for instance, seven of 61 dogs enrolled died during the study or were euthanized shortly after its completion. Of the three deaths that could be attributed to severe acute pancreatitis, two of the affected dogs had received fuzapladib sodium.

"So on the face of it, it wasn't a miracle in this study," Wilson said. "But the findings were promising enough to want to use it in more dogs and see if it makes a difference."

As for adverse effects, Wilson said it's too early to get a complete picture based on safety data released so far in both the U.S. and Japan.

"At this point, it's exciting to have any new drug for acute severe pancreatitis," she said. "Who is the best candidate, at what point in the disease process this drug will provide the most benefit, who shouldn't have it (or when is it too late to expect it to work), and a better understanding of the incidence of adverse effects — we could use more data on all of this."

For diabetic cats, a pill instead of a shot

For many pet owners leery of having to inject insulin in their diabetic cat every 12 hours, relief may be at hand.

A new treatment for diabetes mellitus has been approved by the FDA that entails feeding the patient a single tablet daily.

Bexagliflozin, the active ingredient of the drug brand-named Bexacat, is a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, a class of drugs that have been found to be effective in treating type 2 diabetes in humans. Bexcat's approval marks the first time an SGLT2-inhibiting drug has been approved by the FDA for a nonhuman species.

Diabetes mellitus occurs when the body is unable to process glucose into energy, owing to an inability to respond to, or produce, enough insulin, a hormone that helps cells use glucose. The condition causes an unwanted buildup of glucose in the blood that can do serious damage to body systems such as nerves and blood vessels.

SGLT2 inhibitors like bexagliflozin work by preventing the kidneys from reabsorbing glucose into the blood, instead causing excess glucose to be excreted in urine, resulting in lowered blood glucose.

The FDA advises that Bexacat should not be used in cats that have been treated previously with insulin, or that have a manifestation of diabetes mellitus that requires insulin treatment.

The regulator didn't specify which patients would need insulin injections, or why Bexacat isn't appropriate for patients that have received insulin before. It is broadly understood, though, that SGLT2 inhibitors are effective as a sole treatment only when patients' bodies are able to make their own insulin — which most diabetic cats do.

The FDA added that Bexacat should not be initiated in cats that are not eating well, dehydrated, or lethargic when diagnosed with diabetes.

Serious adverse reactions can include diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), a potentially fatal condition associated with a high blood level of ketones, a type of acid. Risks can be mitigated, the FDA said, by carefully screening cats before and during treatment, and knowing how to quickly recognize and treat serious adverse reactions.

In each of two studies evaluating effectiveness of the drug — an eight-week pilot and six-month field study — more than 80% of patients were deemed to be "treatment successes," indicated by better control of blood-glucose levels, according to the FDA Freedom of Information Summary.

The pilot study, for which 89 cats were enrolled, identified "significant safety concerns" that prompted the researchers to screen more stringently for pancreatitis and DKA, and confirm that cats had a good appetite leading up to treatment. Six cats died naturally or were euthanized during the pilot study.

In the subsequent six-month field study in which 84 cats were enrolled, the number of deaths dropped to three. But in an additional extended-use study that monitored 125 patients that had received Bexacat in previous studies, 49 experienced adverse reactions, 20 of which resulted in natural death or euthanasia.

Determining which patients are suitable for Bexacat and which ones still need insulin isn't necessarily easy to do immediately, according to Dr. Stijn Niessen, who thusly recommends that patients receiving the treatment undergo careful monitoring.

Niessen, an endocrinology consultant for VIN, has been advising on the development of a SGLT2 inhibitor product similar to Bexacat for about a decade. He is excited about Bexacat's approval, pointing out that, judging from research in which he was involved, up to three in 10 diabetic pets are euthanized within a year of diagnosis because their owners can't cope with the insulin-injection regime.

At the same time, Niessen is cognizant of the risks posed by Bexacat.

"Having been involved in developing drugs of this category, we indeed need to acknowledge we are still learning," he said in an interview. "Therefore, we need to keep being open-minded about which patient type is best suited."

An "ill diabetic" patient with poor appetite would seem a bad choice for Bexacat, Niessen observes, whereas a "healthy diabetic" patient would seem a valid candidate. "The risk for DKA seems limited when choosing your patient right, though DKA is certainly something I would advocate owners and attending clinicians to screen for on a regular basis — especially when a cat suddenly becomes unwell."

Equine osteoarthritis injection to replace compounded preparations

Veterinarians long have had access to pentosan injections to tackle osteoarthritis in horses — only the injections are either imported from overseas or compounded.

Now, the FDA has approved a pentosan injection for the painful condition, which involves a slow breakdown of joint cartilage that can cause stiffness, joint swelling and lameness.

Branded as Zycosan, the pentosan polysulfate sodium injection was given to 109 horses during a U.S. field study that also involved 113 control horses injected with a saline solution. The treatment success rate was 57% for horses in the Zycosan group and 36% in the negative control group.

Although the difference in the success rates was not statistically significant, the results of the study varied considerably, depending on the inclusion of three particular cases, and the FDA concluded the study "demonstrated substantial evidence" of effectiveness.

Its approval for Zycosan means veterinarians using compounded products must be wary. Compounding is the practice of creating medications tailored to the needs of an individual patient or a small group of animals by altering the dosage, form and/or flavor of drugs. Use of compounded formulations is not permitted if an FDA-approved drug is available and suitable for the patient.

The FDA has accordingly written a letter to veterinarians reminding them that in order to gain approval, drugs must be rigorously evaluated and their efficacy and safety consistently monitored.

"Unlike FDA-approved Zycosan, compounded and other unapproved formulations of pentosan polysulfate sodium have not been evaluated by the FDA for safety or effectiveness, and may vary in quality, potency, and bioavailability," the letter says.

"Additionally, due to the route of administration of injectable pentosan polysulfate sodium, it is important that it be a sterile formulation to ensure patient safety. The FDA cannot verify the sterility of the compounded products."

The most common adverse reactions associated with Zycosan, the FDA said, were injection-site reactions such as pain, heat and swelling, and prolonged clotting times.