vns_spay_and_neuter

An Australian state has adopted some of the strictest animal reproduction rules in the world, reigniting debate over the pros and cons of mandatory spaying and neutering.

Meanwhile, the World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA) is finalizing an animal desexing survey, destined for thousands of practitioners globally, as it works to create guidelines on what is fast reemerging as a hot-button issue in the veterinary community.

Western Australia, which comprises about 10% of Australia's population but a third of its landmass, in December passed a raft of laws that include a requirement that all new dogs be sterilized by age 2.

The state also will establish a central registration system to hold information on dogs, cats and approved breeders. Pet shops will be turned into adoption centers that may sell only stray, abandoned or seized dogs.

The laws were proposed in 2017 during an election campaign by the left-leaning Labor government, touted as a means of stopping puppy farming. "Dogs are an important part of many Western Australian families and we should be doing what we can to make sure they're looked after and treated well," the state's premier, Mark McGowan, said when the legislation passed.

Exemptions from the mandatory desexing requirement will be granted to people with a breeding license or a letter from a veterinarian certifying that sterilization could adversely affect the animal's health.

Those caught breaking the mandatory sterilization rule could be fined AUD$5,000 (US$3,592).

Spaying and castration of house pets broadly is encouraged in many countries to prevent overpopulation and mass euthanizing. The community at large benefits because a proliferation of unwanted animals may pose safety and hygiene risks to humans. Sterilization can provide health benefits to the animals, such as a reduced risk of mammary and reproductive-organ cancers. Owners can benefit from less pet aggression, wandering and unwanted sexual behavior.

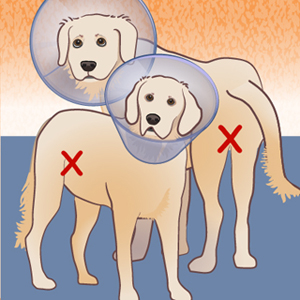

At the same time, the new laws in Australia come as a growing body of research suggests that desexing, especially when animals are prepubertal, might pose health risks, too — such as developing joint disorders and some types of cancer, as well as more well-known risks, such as obesity.

Rhode Island, which mandates desexing cats, is the only state in the United States with a blanket compulsory neutering law, according to the American Veterinary Medical Association. A few local governments in the U.S. also have introduced mandatory desexing — most notably Los Angeles county in 2008, of cats and dogs, according to the AVMA.

Rules often are stricter for animals in shelters: 32 U.S. states, for instance, require sterilization or a promise to sterilize an animal adopted from a shelter or rescue, according to the AVMA. Many jurisdictions throughout the world also impose higher licensing fees for intact animals and mandatory sterilization of breeds considered dangerous, such as pit bulls.

Down Under, the state of Western Australia is not the first to require dog sterilization. The state of South Australia introduced a similar rule for all dogs and cats in 2018, while the Australian Capital Territory, a small jurisdiction that encompasses Australia's capital city of Canberra, introduced the same in 2001.

At the other end of the spectrum, pet sterilization is uncommon in some parts of Europe, such as Norway, Sweden and Switzerland, where the procedures are widely considered to be a form of animal mutilation. Greece, however, reportedly is considering whether to introduce mandatory desexing to address a large problem with strays.

Veterinarians asked to monitor scientific developments

Dr. Jennifer Hood helped formulate the Western Australian rules, having sat on the committee that put them together. In an interview with the VIN News Service, she stressed that veterinarians will have latitude to issue exemptions based on their understanding of the latest science.

"This legislation sounds really tough to a lot of people — they read 'mandatory desexing' and they don't read anything else," Hood said. "But it is up to their veterinarian. A veterinarian is completely capable legally and professionally to come to the conclusion that an animal should be exempt."

Mandatory desexing is the default position, so pet owners in Western Australia will have to argue if they don't want to sterilize their animal.

Hood said the legislative committee reviewed the scientific literature before making recommendations. The review, completed in 2018, references papers that explore the potential negative influence of desexing on a variety of health conditions, including joint problems, cancer, urinary incontinence, autoimmune disease and poor spatial navigation, among others.

Noting that research in the field is ongoing, Hood said the Western Australian legislation is designed to accommodate the emergence of further scientific evidence. "The legislation really does behoove practitioners to keep up-to-date on the science now because the public will be asking more questions," she said. "It's a heated topic, so vets really need to be well-informed and give their clients the right information so they can make informed choices."

Hood said veterinarians may want to consider owners' personal circumstances in addition to potential impacts on pets' health: For instance, a veterinarian presented with a large-breed male dog might ask owners about their capacity to contain the dog if it's left intact. If their house has poor fencing and the dog has been known to roam in the past, a veterinarian might opt to turn down a request for an exemption.

"Everyone who's involved in the decision needs to weigh what's best for the animal and what's best for the community as a whole," Hood said. "We're having to do that with COVID in our everyday lives — so people are now beginning to understand that they have to balance their rights against the common good."

Hood rejects the suggestion that placing so much onus on veterinarians will leave them exposed to unnecessary regulatory risk. "That's already the case for a lot of things — veterinarians are legally responsible for many decisions," she said, "and if they make poor clinical choices owners can and do complain to surgeons boards."

Even so, Hood said she'd welcome efforts by professional associations to help veterinarians stay abreast of relevant scientific and public policy developments.

WSAVA taking global temperature, creating guidelines

Coincidentally, the WSAVA is doing just that, having last year formed a reproduction-control committee with the aim of helping practitioners make science-based choices. The committee, chaired by Padua, Italy-based reproduction specialist Dr. Stefano Romagnoli, comprises specialists based also in Australia, Austria, South Africa, Thailand and the U.S.

Romagnoli said the committee's first task will be to survey veterinarians in the coming months on if, how, when and why they are spaying and castrating pets. The survey will ask, for instance, what techniques they use, be they surgical or nonsurgical, and at what age animals are altered. (Drug-based nonsurgical techniques that provide temporary sterilization have been growing in popularity in recent years but have yet to attain widespread use).

"Attitudes towards spaying and neutering absolutely are changing," Romagnoli told VIN News, acknowledging that scientists are discovering more associated health hazards, though with varying degrees of certainty. "We're trying to come up with a new paradigm, which doesn't mean we won't be spaying and neutering any longer, but recognizes we need to make decisions based on different factors, rather than just the convenience."

Romagnoli said the committee already is working on guidelines that will be informed by the survey results. He said the committee is hoping to present at least some, if not all, of its guidelines at the WSAVA's next annual conference, scheduled in October in Peru.

Taking a broad look at reproduction, the committee will also examine aspects such as surgical intrauterine insemination, where sperm is placed directly in the uterus, and how often females should become pregnant in their lifetimes. The committee's work will help WSAVA come up with official stances on many reproductive issues, including mandatory sterilization, Romagnoli said.

Opinions on mandatory desexing vary markedly in the veterinary community, with detractors often arguing that such decisions are a personal matter for pet owners. Some worry that pet owners may become reluctant to seek medical care for their animals for fear of being reported for failing to desex them.

The American College of Theriogenologists, an organization that certifies animal-reproduction specialists in the U.S., is among groups that oppose mandatory desexing. Its official position is that while animals not intended for breeding should be sterilized, the decision must be made on a case-by-case basis between pet owners and their veterinarians. Factors to take into consideration, it posits, include the pet's age, breed, sex, health status, intended use, household environment and temperament.

"While there are health benefits to spaying and neutering, these must be weighed against the health benefits of the sex steroids," the college states. "Additionally, research has shown that in locations where mandatory spay and neuter programs have been instituted, a decrease in the number of vaccinated and licensed animals has been seen due to poor program compliance from pet owners' fears of seeking veterinary care if their animals are still intact."

Enforcement a potential challenge

Mandating sterilization doesn't necessarily mean much will change, if experience in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) is a guide.

Prepubertal desexing has been a legal requirement in the ACT for more than 20 years: Cats must be desexed by 3 months of age and dogs by 6 months.

Enforcement, however, appears to be lax; many veterinarians don't even know the rules exist, according to research published in the journal Frontiers in Veterinary Science in 2019.

The researchers found that 35% of 52 veterinarians surveyed in the ACT were unaware that prepubertal desexing was mandatory there. Asked whether they thought it should be mandatory, 46% said "definitely not," 21% said "maybe" and only 12% said it "definitely should."

Not a single respondent advised clients to desex their dogs before 4 months of age, with 71% recommending clients do so at 6 months or older. For cats, only 10% recommended clients desex before 3 months of age. Most respondents advised clients to desex their cat before 5 months (38%) or 6 months or older (40%).

How vigorously the ACT has pursued enforcement is unclear. During most of the time the law has been in place, infringement records were paper-based and are unavailable for analysis, the researchers found. Since September 2017, when records became digital, 15 cases were logged of individuals being fined for keeping intact dogs without a permit. No data were available from the government about cats.

"We conclude that prepubertal desexing might be poorly supported by veterinarians in the ACT even though pets are legally required to undergo prepubertal desexing," the researchers said. "As a result, veterinarians may unintentionally be limiting access to this procedure. This has wider policy consequences for Australian and overseas jurisdictions which are considering introducing mandatory prepubertal desexing."

The Western Australian government, by setting its desexing deadline at 2 years old, affords pet owners more flexibility than the ACT. "Two years is really good, I think. It allows bitches to have a season," Hood said, referring to the period when female dogs go into heat, or estrus, and can become pregnant.

Hood accepts that the effectiveness of the rules she helped formulate will, in part, depend on how hard the Western Australian government tries to enforce them.

At the same time, she said, the rules will make it easier for agencies to enforce other laws, such as those designed to prevent cruelty to animals. "It can be difficult to get a warrant to enter a property, but if a neighbor sees puppies running around over the fence and they're not registered, it offers a precursor for other rules to come into play and further protect the animals.

"But even in a worst-case scenario of poor enforcement," she added, "I think if vets are at least made more aware of their responsibilities, it can only be a good thing if they have more informed discussions with their clients about sterilization — the pros and the cons — and help owners understand there isn't a one-fit answer in most cases."