vns_faces_art

There are 121,461 veterinarians in the United States, according to the profession's biggest association. But ask the U.S. government, and it will tell you there are either 73,710 or 104,000, depending on how they are counted.

Separately, an organization representing state veterinary regulatory boards tries to keep tabs on who's practicing where. But it doesn't have an accurate tally of the veterinary population nationwide.

So how many veterinarians are there, anyway? And does it even matter?

The second question is easier to answer than the first.

Knowing the size of the profession provides valuable information for making big decisions affecting veterinarians, animals and their owners. Is there really, as many people say, a shortage of veterinarians? Are there enough veterinary schools? Are people leaving the profession in droves because they're overworked?

Figuring out the answers to those questions is difficult and involves considering many moving parts, such as the type of veterinarian in demand (companion animal, food animal, equine or the like), how many hours a week they work and how efficiently they do their jobs. Even so, knowing the total number of veterinarians that exist is a fundamental factor to consider, according to economists.

"You need multiple data points to understand what's going on, but you have to start somewhere," said Ryan Williams, associate professor of economics and public policy at the Texas Tech School of Veterinary Medicine. "Ideally, as a researcher, it would be wonderful if we knew everything about every vet in the country. But an aggregate of data is a good first step."

The pandemic arguably has made it even more important for decision makers to arm themselves with accurate data. Anecdotal reports of burned-out veterinary teams, and patients dying because owners can't find emergency care, have brought a greater sense of urgency to conversations about the state of the profession.

The VIN News Service took a long look at how practitioner numbers are calculated, why they might differ by source and how they are counted in some other countries.

It all starts with the states

In order to practice as a veterinarian in the U.S., qualified individuals must obtain a license from their state veterinary board. Licensing is not done at the federal level, which makes taking a national tally tricky from the outset.

The American Association of Veterinary State Boards, which represents all state and provincial boards in the U.S. and Canada, keeps a proprietary database of licensed veterinarians. But it faces challenges keeping that database up-to-date.

"We don't really have a number [of practicing veterinarians] to provide from the database," said AAVSB Executive Director Jim Penrod. "If we don't have information that they're deceased or chosen to let the license lapse, it's not going to be accurate."

State-based veterinary medical boards, Penrod explains, often rely, imperfectly, on employers or family members telling them when veterinarians retire or pass away.

The ability of veterinarians to practice in more than one jurisdiction further muddies the picture. A licensee in one state could be licensed in other states simultaneously, creating the possibility of being counted more than once.

Veterinarians in the U.S. typically must renew their license every one to three years, depending on the state. Although the AAVSB's central database excludes veterinarians whose licenses have expired, it doesn't always receive timely updates, Penrod said.

The AAVSB is working with California's board to create a database connection that would allow it to receive daily updates. "This will serve as a model for other state boards to ensure our centralized licensure database is accurate and current," Penrod said. "The AAVSB board of directors has authorized funding for us to assist state boards with the IT [information technology] costs associated with making these connections."

Challenges collating state-based numbers haven't stopped some organizations from giving figures for the number of veterinarians nationwide.

The AVMA and its bigger number

The American Veterinary Medical Association was established more than a century ago to represent the interests of the U.S. veterinary profession. Membership in the AVMA isn't mandatory in order to practice; many veterinarians join to access benefits including insurance products, career services and practice-management tools.

Every year, the AVMA estimates how many veterinarians there are in the U.S., including those who aren't members of the organization. Its latest number is 121,461, as of Dec. 31, 2021, according to AVMA spokesperson Mark Rosati.

The AVMA's annual updates are based primarily on graduation data provided by veterinary schools. Its method for tracking individuals' movement in and out of the profession at other points in their lives is less definitive.

Asked for details about the method, Rosati would say only: "We periodically ask our members to update their employment information so we can provide more personalized service to our members and study the continuously changing demographics of the profession." The number of AVMA members, he said, is "more than 99,500," which is about 82% of the total number of veterinarians in the association's tally.

A former senior employee of the AVMA maintains that the association's methodology is far from perfect. Michael Dicks, the organization's chief economist between 2013 and 2018, said that during his tenure there, veterinarians may have been overcounted.

"A large percentage of members provide no information to the AVMA or incomplete information specifically on the type of practice they are involved in, or if they are still actively practicing," Dicks said in an interview. "Some may end AVMA membership as a result of retirement, disability, death or simply leave the profession, and this person would still be on the list of veterinarians."

At one point, he probed the age distribution of AVMA members and discovered that some were over 100 years old, he said.

On the plus side, Dicks said, "The nice thing is that they know every single veterinarian that has gotten a degree in the United States and abroad or has gotten a certification here. They do have a very good idea of the total number of veterinarians that is possible to be here, but they don't have much else."

Before he left the organization, Dicks said, the AVMA was working on a modeling system to assess the number of practicing veterinarian. Collecting and validating data to feed into the model each year would be an expensive undertaking, he added.

Responding to Dicks' observations, Rosati said AVMA estimates are calculated "by a team of AVMA staff, including colleagues from our membership and economics division, all of whom are committed to accuracy, as is the leadership of the organization."

The AVMA takes great care in collecting and maintaining its data and does not inflate numbers, Rosati said.

He confirmed that the membership figure includes retired practitioners, explaining that the organization is dedicated to serving veterinarians at all stages of their professional lives, including retirement. "The AVMA does its best to keep our membership numbers and members' information up to date, meaning that we are just as careful about removing individuals from our member roster when we learn they are deceased as we are about identifying new veterinarians who join the profession."

Rosati said a review of its records shows that the oldest veterinarian it currently has listed as actively engaging in practice is 95 years old. "There is a very small number of retired veterinarians who are older," he said.

The BLS and its smaller numbers

Another source of veterinarian population figures is the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The federal agency is responsible for producing official economic data such as unemployment and inflation figures that influence crucial monetary policy decisions made by the Federal Reserve.

According to one commonly referenced section of its website, the BLS says 73,710 veterinarians were employed in the U.S. as of May 2020, earning a mean annual wage of $108,350. That's 47,751 veterinarians fewer than in the AVMA count for 2021.

The BLS figure is derived from the Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS) survey, an annual poll of around 1.1 million businesses. The survey involves respondents submitting data online, and the results are extrapolated to produce national estimates of the number of people in given occupations and earnings.

BLS economist John Jones told VIN News that the 73,710 figure excludes "self-employed" veterinarians. By that, he means locum practitioners who offer their services as freelancers. Owner-operated businesses that employ solo veterinarians are counted in the survey.

Using the OEWS data, the BLS also estimates the distribution of employed veterinarians across each state. California, for instance, has more veterinarians than any other, with 7,490, according to its latest figures.

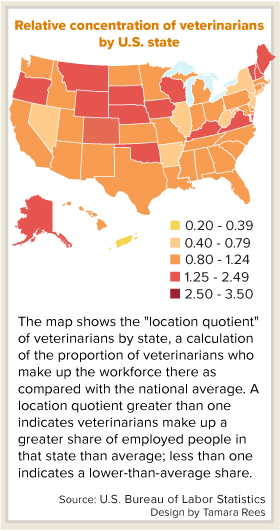

To assess whether some places have a greater need for more veterinarians than others, the agency calculates for each state a "location quotient" — a ratio expressing relative concentration of veterinarians. A location quotient greater than one indicates an occupation has a higher share of employment than average; less than one, a lower-than-average share.

U.S. states with the highest concentrations of veterinarians are South Dakota, Montana and New Hampshire, with ratios of 1.97, 1.92 and 1.88, respectively. Those with the lowest include New Jersey, Arkansas and Illinois, with ratios of 0.65, 0.69 and 0.74, respectively.

The OEWS isn't the only way the BLS counts veterinarians. Separately, it carries out a Current Population Survey (CPS), which Jones said is a monthly poll of 60,000 households conducted via telephone and in-person interviews. Unlike the OEWS, the CPS counts "self-employed" veterinarians and those on leave without pay. That survey's number for the nation in 2021, also based on an extrapolation of survey results, comes in at 104,000 veterinarians — which Jones notes is closer to the AVMA's 121,461.

It's difficult to tell why the BLS and AVMA numbers differ, Jones said, because the AVMA doesn't publish its methodology.

For his part, Rosati at the AVMA said the BLS approach is "more prone to measurement error" because it's based on extrapolated survey data, as opposed to the AVMA approach, which he called "transactional."

How it's done overseas

More precise methods for measuring the size of the veterinary workforce are used in the United Kingdom, where a national tally is done annually by the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, the country's official regulator of the profession. Only veterinarians registered with the RCVS are allowed to practice in the U.K., and they must pay to renew their membership every year, making their status relatively easy to track.

The RCVS's latest annual "Facts" report, released in July 2020, provides numbers from the 2018 calendar year, when 31,338 veterinarians were registered with the organization.

RCVS spokesperson Zoe Dowsett said the college's numbers are regularly reviewed, and account for various change factors, such as people dying or leaving the profession. "We can get an immediate up-to-date figure on all our members' registration movements with reasons," Dowsett said by email. "For example: Numbers that left the register, changed their practising status — on a particular date and why." Tracking is carried out, she added, by a team of RCVS officers, who log changes as they occur on a central database.

Other countries are similar to the U.S. in having less centralized registration protocols. In Canada, for instance, licensing occurs at the provincial level. The Canadian Veterinary Medical Association estimates there are currently 15,118 practitioners in Canada.

CVMA member services manager Denise Charron said the association calculates the number by asking each provincial regulatory body in Canada how many licensed veterinarians existed in their province or territory at the end of each year. It then adds those numbers. "However, we do state that it is approximate because [numbers] can change quickly in each province," Charron said. "We do have some veterinarians licensed in more than one province, and we don't get updates from the provincial regulatory bodies every time someone has a change in their license status."

Australia's chief professional lobby group, the Australian Veterinary Association, conducts a biennial survey of veterinarians. Participation is voluntary. The association largely relies on state-based information to estimate national numbers.

The latest available data indicates that registered veterinarians in Australia totaled 13,993 on Aug. 3, 2021. The AVA sourced that number from a tally provided by the Australasian Veterinary Boards Council, a representative body of the country's state veterinary boards. The AVA received 3,770 responses to its latest survey, an estimated response rate of 26.9%, judging from the number provided by the AVBC.

Dr. Cristy Secombe, the AVA head of veterinary and public affairs, said that like in the U.S., registration data may not always take accurate account of people leaving the profession, be that via a career change, retirement or death. "Getting accurate data of the size of the workforce is very difficult with the current reporting mechanisms," she said.

The upshot

In sum, countries such as the U.K. that have national registration systems for veterinarians appear able to count their veterinary population more exactly than those that license practitioners state by state or province by province, such as Australia, Canada and the U.S.

Williams, the veterinary economist at Texas Tech, believes that in the absence of a more cohesive and centralized licensing system in the U.S., the federal government's count of the veterinary population is the best source. "The BLS numbers are probably as good of an estimate as there is, but they're probably on the low side in terms of practicing veterinarians," he said.

"The trouble with data like that is that it takes an agency having the desire to know the actual number at any given time and a willingness of people to inform that agency of their participation in that market."

By contrast, Clinton Neill, assistant professor of veterinary economics at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, tends to reference the AVMA data, though he recognizes that those figures are flawed, too. "The barriers are largely getting people to respond to surveys," he said. "There's a lot of survey fatigue around veterinarians."

Multiple sources stressed that calculating overall veterinarian numbers is just one piece of the puzzle. Dicks, the former AVMA chief economist, would prefer the supply side of the supply/demand equation was measured not by veterinarian numbers, but by the hours of service veterinary teams can provide.

Then there's the demand side to consider, such as how many animals need veterinary attention and how often, which is a different story altogether.

Williams sees limits to how much more organizations can do to count things without the whole endeavor creating more trouble than it's worth. "Could we do better? Does anyone have an incentive to spend the money and time to do better? I don't know," he said.

Nobody doubts, though, that trying harder to answer the simple question of how many veterinarians there are is a worthy cause. "If we can get better numbers, we can answer some of these big questions that are really plaguing the industry," Neill said:

"Do we have enough veterinarians? And are they in the right places?"