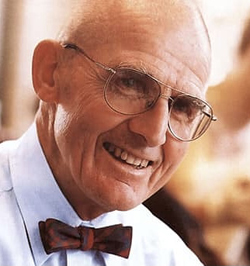

The veterinary legend known affectionately as Dr. D

Famed neurologist, anatomist Dr. Alexander de Lahunta remembered

Dr. Alexander de Lahunta

Facebook photo

Dr. Alexander "Sandy" de Lahunta died on Aug. 17. He is survived by his family, friends, former colleagues and countless students to whom he imparted knowledge, wisdom and enthusiasm for veterinary medicine.

Dr. Susan Wylegala recalls waking well before sunrise as a student, determined to get to Cornell University's veterinary teaching hospital in time for daily 3 a.m. neurological exams with Dr. Alexander de Lahunta.

Neurology wasn't a special interest for Wylegala, but like the venerated neurology and anatomy professor himself, rounds with de Lahunta — known by most as Dr. D — were legendary. The professor's enthusiasm for veterinary medicine was infectious, she said, and she didn't want to miss a moment. Neither did her classmates, some of whom slept in school hallways to ensure that they'd be there.

"There was just an aura around him," Wylegala recounted to the VIN News Service. "He had such a passion for education and a passion for neurology, and he loved sharing that. It was incredible to see him work with animals. You just wanted to be there to witness it. Those mornings are really some of my fondest memories."

De Lahunta died Aug. 17 at age 88. His wife of 56 years, Patricia, died in 2011, and he is survived by their children Scott, Harry, Brian and Leslie and their families, which include nine grandchildren. He also leaves behind his partner, Shirley Reed Dutton.

When not in the office, de Lahunta enjoyed spending time outdoors with loved ones, cycling, backpacking, playing ice hockey and running marathons, which he often trained for around campus, even during harsh Ithaca winters.

Wylegala, who now owns a practice in Buffalo, New York, is one of many mourning the loss of de Lahunta, whose online obituary is heavy with tributes. Former students from all over the world have shared stories of Dr. D on social media forums and listservs, marveling that they were educated by a pioneer in veterinary neurology considered one of the profession's greatest mentors and teachers.

"Such an inspiring teacher with such incredible energy. I am so glad I was lucky enough to experience rounds with Dr. D!" Dr. Emma O'Neill, a veterinarian at University College of Dublin, wrote in a recent Facebook post.

"His towering mind was intimidating, but I'll never forget how he calmed my fear during his oral exams to get to the right answer," added Dr. Elisa Salas, an anatomic pathologist in Lincoln, Nebraska. "I'll always remember the suspensory ligament and the succulent nucleus pulposus."

Advancing the profession

Born and raised in Concord, New Hampshire, de Lahunta graduated in 1958 from what then was known as the New York State College of Veterinary Medicine at Cornell University, and settled in his hometown as a mixed animal practitioner. He returned to Cornell for graduate study in 1960.

De Lahunta is described by many as humble, but his achievements during 42 years on Cornell's faculty are anything but. Before earning a doctorate in neurology in 1963, he was hired by Cornell as an anatomy instructor and later, an assistant professor. In the ensuing years, he became a full professor, chief of the medical and surgical section of the veterinary teaching hospital, and later, its director. He chaired the veterinary program's anatomy and neurology departments, and in 1992, he was named the James Law Professor of Anatomy.

De Lahunta started Cornell's program in clinical neurology and was among a group who established the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine and neurology as a specialty. Alone and in collaboration with colleagues, he published five text books and authored 266 peer-reviewed articles.

Throughout his career, de Lahunta identified and studied many neurological diseases afflicting animals. One he found most exciting was coonhound paralysis, a condition that had been recognized for years in hunting dogs but for which a cause was unknown, according to an interview with de Lahunta published in 2015 in Connections, the New York State Veterinary Medical Society magazine.

Widely suspected causes at the time made little sense, he said: "They wanted to make it a spinal cord lesion from the dog leaping on the tree after a raccoon," but the clinical signs in patients pointed to a lesion affecting the neuromuscular system. De Lahunta and his colleagues hypothesized that the cause was inflammation, of unknown origin, of the nerve roots. They were right. The diagnosis: acute canine idiopathic polyradiculoneuritis, a creeping paralysis due to acute nerve inflammation.

"It is an animal model for a human disorder — Guillain-Barré Syndrome," de Lahunta said in the interview. "Fortunately, most of the dogs and people recover in time, but some do have to be put on a respirator for a period of time in order to recover."

De Lahunta's college, university and national accolades are so numerous, they're difficult to summarize. Last year, he received the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine Lifetime Speciality Achievement Award for neurology. "Those of us who had the great fortune of working with Dr. de Lahunta easily conclude that he was the single greatest and most dedicated teacher we have ever known," reads a nomination letter signed by his colleagues.

The letter described the professor as so committed to the program, the Cornell University Registrar's office once calculated that he had more contact hours with students than anyone else at the institution. "To accomplish so much, a person would need to be remarkably efficient, and Dr. D is efficiency personified," the letter reads. "We can honestly state that he was the most dedicated, focused, efficient veterinarian with whom we have ever worked."

De Lahunta has also received the Daniel Elmer Salmon Award for Distinguished Alumni Service (2008) and the ACVIM Robert Kirk Award for Professional Excellence (2000). He earned honorary memberships from the American College of Veterinary Pathologists and the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons.

In 2016, a group of Cornell alumni honored de Lahunta with an endowed scholarship in his name. "I certainly never regretted a moment of the 45 years that I was on the faculty of Cornell," de Lahunta said during a recorded response expressing his appreciation.

Drs. Marc Kent, Alexander de Lahunta, Eric Glass

Photo courtesy of Dr. Eric Glass

Drs. Marc Kent, Alexander de Lahunta and Eric Glass (left to right) collaborated on cases involving neuroanatomy, embryology and neuropathology, which resulted in numerous publications. "Whoever said anatomy is a dead subject? Only the cadaver is dead!" de Lahunta quipped.

A lasting impact

De Lahunta retired in 2005, having spent much of his career teaching veterinary neuroanatomy and clinical neurology to first-year students. On and off, he also taught gross anatomy, embryology and applied anatomy and neuropathology, ensuring that four decades-worth of Cornell graduates were educated under his tutelage.

Of all his accomplishments, he considered teaching to be the greatest. He got to know his students, mentoring them and staying in touch until his final days.

Dr. Eric Glass, a veterinary neurologist in Tinton Falls, New Jersey, is one of them. A 1995 graduate of the veterinary program who completed his residency in 1999, Glass says de Lahunta helped him realize the profession was his calling. Post graduation, he collaborated with de Lahunta and another veterinary neurologist, Dr. Marc Kent, on cases that led to numerous publications correlating neuroanatomy and clinical neurology.

From his student days, Glass remembers de Lahunta leaving his office door open so his textbooks and teaching materials could be accessed at all hours — typical of a man who spent his career thinking of better ways to educate his students.

"Dr. D was a simple person who had no airs," Glass wrote in his dedication to the fifth edition textbook, de Lahunta's Veterinary Neuroanatomy and Clinical Neurology, which he and Kent co-authored with de Lahunta, published last year. "Perhaps this is why he likes being called simply 'Dr. D.' … Every time a student asked him a question, he would answer as though he were talking to a friend.

"… Above all else, Dr. D was humble and modest with his ideas and scientific discoveries, always giving credit to others who participated in any and all products," Glass continued. "He really did not care who received credit as long as the work was done and discovery was made and, most importantly, shared."

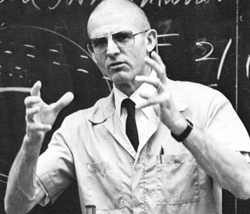

Dr. D

Cornell University photo

Dr. D drew on the blackboard with such speed that some struggled keep up. "I was in awe of his ability to illustrate, in colored chalk and drawing with both hands simultaneously, embryonic structures and spinal anatomy," Dr. Doug Aspros of New York wrote on a memorial page.

Dr. Paul Pion, a veterinary cardiologist who graduated from Cornell in 1983, recalls running into de Lahunta while studying anatomy between 2 a.m. and 4 a.m. "I didn't sleep much then, and I needed to touch the specimens myself and visualize them, and that didn't happen easily in a group during the day sessions," he said. "Dr. D would usually arrive on campus on his bicycle between 3 and 4 a.m. ... He'd come in and find me at my cadaver and say, 'It's mighty late, Mr. Pion,' to which I'd respond, 'It's mighty early Dr. D,' and then he'd move on."

Pion, cofounder of the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and VIN News parent, said one of his fondest memories of his time at Cornell was taking clinical anatomy. "Dr. D taught the class in third year. He would take one full week of his days to give the exams. Each of us (80 in the class) would spend 30 minutes taking an oral exam from Dr. D, one on one."

As part of one exam, de Lahunta asked Pion to palpate the greater trochanter on a cow. "I pointed to the ischial tuberosity," he said. "Dr. D gently took ahold of my wrist and slowly slid my hand over to the greater trochanter and said, 'Riiiight.' My nervousness immediately melted away."

With admiration and reverence

De Lahunta showed sensitivity to his students' diverse needs. On the online obituary page, there is a reflection by Dr. Robert Efron, a 1975 Cornell graduate, in which he shared how de Lahunta — "a very busy, famous and brilliant professor" — went out of his way to act in deference to students' Jewish faith and heritage.

Most Jewish students didn't attend classes during Yom Kippur, the holiest day in Judaism, Efron wrote, so professors typically did not introduce new material that day. But Dr. D wouldn't waste a day of study. Instead, he'd reteach his lessons to Jewish students at sundown, when the holy day ended.

"He donated his time for the benefit of his students. He was truly one of a kind," wrote Efron, who practices in Cromwell, Connecticut.

In an online tribute, Dr. Craig Williams, a 1977 Cornell graduate from New Hampshire, recounted a memory from 1983, as he sat on a rock overlooking Rye Beach on New Hampshire's coast.

Dr. Alexander de Lahunta - 1988

Cornell University photo

"Nobody called him Dr. de Lahunta. Everyone called him Dr. D," said Dr. Susan Wylegala, a 1988 graduate of the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. Wylegala is on the left, holding a book, in this 1980s image.

"I noticed a man walking up the shoreline about 400 yards away, not just walking but devouring and observing every detail as he walked," Williams wrote. "Immediately my mind said 'de Lahunta!' I walked down to the sand to intercept, 10 feet away, and he pointed to me. 'Williams 77,' he said. Unforgettable, amazing man and teacher."

Dr. Chris Boshart-Adamson, a 1996 Cornell graduate who practices in New York, wrote that she thinks about de Lahunta every time she examines a pet with possible neurological disease, thanks, in part, to the vast array of neurological exams he shared with his students.

Two such cases have stuck with her, including the pathognomonic gait of a dog with contracture of the infraspinatus tendon, as well as the appearance of a dog with tetanus. "Thanks to Dr. D," Boshart-Adamson wrote, she could observe the dogs from a distance and immediately say, "Oh! I know what he has!"

Boshart-Adamson concluded, "You will live on, Dr. D."