Photo by Laura Sherr

Dr. Shawn Johnson, aided by veterinary technician intern Ben Calvert, listens to the lungs of a sea lion pup at The Marine Mammal Center.

At marine mammal rehabilitation centers along the California coast, March and April usually are elephant-seal season. This year, the facilities are swamped instead with sea lions.

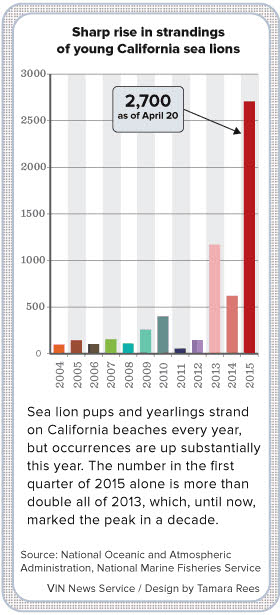

Extraordinarily high numbers of stranded young sea lions have been making headlines across the nation. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) declared the situation an “

unusual mortality event” demanding immediate response, and attributes the problem to a lack of high-quality, close-by food sources for nursing sea lion mothers.

During the first three months of the year, 2,250 sea lion pups and yearlings had stranded, compared with 35 in a normal year, according to NOAA spokesman Jim Milbury. Undersized, starving young animals continue to show up on shore. The

tally reached 2,700 this week.

At the same time, the population of

California sea lions as a whole is robust, numbering approximately 300,000, Milbury said.

In fact, record numbers of adult male sea lions are congregating at the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon this spring to feed on smelt and salmon, according to a recent

report in the

Seattle Times.

The overall population is about 10 times what it was before the Marine Mammal Protection Act came into place in 1972. Does today's boom-and-bust situation suggest that the California sea lion population has reached its maximum? It's an open question; factors driving the bust are complicated and murky.

Asked whether the food shortage for sea lion mothers was due to overpopulation, Milbury replied, “I believe that the carrying capacity of the ocean environment for sea lions may have reached its limit, but when you have a slight change in the environment, the carrying capacity changes.”

This year, warm water caused prey to move away from sea lion mothers' usual foraging grounds. Normally, the mothers nurse their pups for a day or two, then leave the young ashore while they swim to nearby feeding areas. They typically are away for two to five days. This year, there simply isn’t enough food to go around, according to Nate Mantua, a climate research scientist at NOAA's Southwest Fisheries Science Center in Santa Cruz, and so the mothers are gone for longer than usual.

Left without their moms, the pups try to wean themselves. But they are too young, inexperienced and weak to hunt effectively, and quickly starve, Mantua said.

“It’s an issue of supply and demand, and demand now is very high,” Mantua said. “The breeding mothers in the Channel Islands have to have a lot of food within range, in foraging distance. Mothers were feeding on market squid and rockfish but the caloric content is not as high as in sardines or anchovies. In the past few years, the sardine population has declined dramatically. The onset of exceptionally warm ocean conditions in 2014 likely caused a northward shift in the distribution of some of their preferred prey, too.”

The Pacific Ocean currently is in an El Niño, a climate phenomenon in which sea-surface temperatures are anomalously high. El Niños are known to exert huge changes in the ocean and weather, but El Niño doesn’t fully explain the sea lions’ problem, Mantua said. While ocean temperatures off the West Coast are warmer than usual this year, that wasn’t the case in 2013, another year in which high numbers of sea lions stranded on the California coast. That time, the water was colder than usual.

Whatever the cause, veterinary staff at the eight marine mammal rehabilitation facilities in California are exceptionally busy.

“We're seeing (sea lions) that are almost two years old, and they are the exact same size as 9-month-olds,” said Dr. Shawn Johnson, veterinary director of The Marine Mammal Center (TMMC), based in Sausalito. “They've survived but they haven't grown.”

Some pups come in weighing less than they should have weighed at birth, which is 13 to 20 pounds.

TMMC covers 600 miles of coastline, from Mendocino to San Luis Obispo counties.

The situation is worse in Southern California, where sea lions breed in the Channel Islands near Santa Barbara.

To handle the number of sea lion patients, SeaWorld in San Diego built two temporary pools, each capable of housing 20 animals.

Spokesman David Koontz said SeaWorld brought in staff from SeaWorld and Busch Gardens parks around the country to help. It also closed a sea-lion show for nearly three weeks to free trainers to assist in rescue. In an average year, SeaWorld rescues between 150 and 200 sea lions; the number this year exceeds 700.

At TMMC, the count on sea lion patients treated so far is 854.

Normally, pups nurse for 10 to 11 months — far longer than other pinnipeds — and wean around May or June. Every year, some number of newly weaned pups strand, but usually not until June or July.

"That's when we normally see them — those groups that haven't figured it out," Johnson said. "This year … we started the year with over 50 animals.”

The first pups began showing up on beaches in December. Many of those were just above normal birth weight. SeaWorld’s Koontz said a greater percentage of those died. The animals being rescued now are older and heartier and have slightly better body conditions.

The volume also is beginning to diminish. At the peak, SeaWorld rescued 20 pups in one day. They’re down now to three to six per day.

Other marine mammal species, meanwhile, appear not to be struggling in the same way. For example, strandings of Northern elephant seals, some of which become orphaned between mid-February through June when they’re washed from their rookeries by storms, are not greater than usual.

The rescue processOnce a facility is notified about a stranded mammal, the animal is removed from the beach by trained personnel — staff or volunteers, depending on the organization.

The TMMC approach is to send two or three people armed with a net and herding boards, which are wooden or plastic shields about 3½ feet high. The animal is carried or guided into a dog travel kennel.

The animal gets a tube-feeding at the Sausalito center or, if farther away, a TMMC triage center, before transport to Sausalito for its first veterinary examinations.

At intake in Sausalito, each animal gets a physical examination; a blood draw for a complete blood-chemistry and biochemical analysis; fecal analysis for parasites; and a prescription for individual treatment. Like other pinnipeds at the centers, sea lion pups are rehabilitated for four to six weeks, then returned to the wild. Any deemed unable to survive in the wild for health or behavioral reasons are moved to an aquarium or zoo for permanent care.

All rescued animals are tagged, and their ID numbers entered in a database shared by all the facilities on the West Coast, so that they’re identifiable if they wash ashore again.

The biggest health problem Johnson sees in the sea lions is starvation; pups that shouldn’t be weaned yet are emaciated and dehydrated. They’re so young that they have trouble digesting food given to them. Some have gastric ulcers. Many also have severe open ulcers on their flippers caused by a calicivirus called San Miguel sea lion virus.

The first focus is to hydrate the pups. After an injection of antibiotics, subcutaneous fluids are given with an electrolyte solution. Intravenous fluids aren't used because the animals’ peripheral veins are not easily accessible. As members of a species that lives in cold water, their blood vessels are deep; only the jugular is accessible.

Once the patients are hydrated and stable, tube feeding begins with a fish slurry – basically, a herring milkshake. Vitamin B is added for the first three days, followed by a daily multivitamin designed for marine mammals.

Parasites aren’t found in pups that haven't eaten solid food yet, but older animals tend to have a heavy burden of tapeworms. Yearlings generally have a lot more parasites than pups. During El Niño years such as this one, more sea lions have pneumonia from lungworms (

Parafilaroides decorus). Opaleye fish are an intermediate host for lungworm. Dr. Laurie Gage, a former veterinary director of TMMC, guesses sea lions are eating more opaleye than usual.

“My suspicion is that, for some reason, perhaps the opaleye aren't as inclined to go out to deeper ocean,” Gage said — making opaleye the one fish that pups are able to catch.

Sea lions afflicted with lungworm pneumonia are treated with ivermectin and fenbendazole, along with steroids or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as carprofen.

Bacterial pneumonia involving

Pseudomonas or

Salmonella is another common condition, mostly secondary to immune suppression stemming from starvation.

“Because we have so many (animals) now, we are following herd-health protocol,” Johnson said. “We start with ceftiofur, which is used in cattle and lasts for seven days. We give one injection. These are wild animals and it’s difficult to give oral medication. When you have 200, it's too hard to give oral meds twice a day. It’s hard enough just to feed them, let alone give meds. We focus on long-acting meds, and if they don't respond, we switch to a different one.”

Beyond starvation and pneumonia, patients may have fractures; bite wounds and resulting abscesses; or corneal ulcers. Surgery is called for regularly. Sometimes amputation of a hind flipper is necessary; sometimes fractured jaws require repair; sometimes debris stuck around necks must be removed surgically.

See a beached animal? Let experts handle it

- Northcoast Marine Mammal Center, Humboldt and Del Norte counties, 707-465-6265

- The Marine Mammal Center, Mendocino, Sonoma, Marin, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Cruz, Monterey and San Luis Obispo counties, 415-289-7325

- Santa Barbara Marine Mammal Center, 808-687-3255

- Channel Islands Marine & Wildlife Institute, Ventura County, 805-567-1506

- California Wildlife Center, Malibu, 818-222-2658

- Marine Animal Rescue, Los Angeles County, 800-399-4253

- Pacific Marine Mammal Center, Orange County, 949-494-3050

- SeaWorld, San Diego County, 800-541-7325

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, West Coast Region Stranding Hotline, 866-767-6114

Dangers to come

As summer approaches and water temperature rises, sea lions will face other threats.

The first case of domoic acid toxicosis in marine mammals was diagnosed in 1998, and now hundreds of sea lions are diagnosed every year. The condition is caused by a toxin produced by single-celled organisms called diatoms (Pseudonitzschia australis), a type of algae, which blooms in warm water. The diatoms are eaten by fish, which in turn are eaten by sea lions. Domoic acid affects the hippocampus.

"You'll have a big, fat, healthy sea lion with seizures as a result," Gage said, "and about all you can do is support them. If they ate too much fish with this domoic acid in it ... there is damage to their brains. If they recover, they may be more docile than unaffected sea lions, and there are concerns they won’t be able to navigate. If they are stable, they may be placed in a captive situation, versus being released back to the wild.”

(Humans and birds, too, are susceptible to domoic acid poisoning. Fish and shellfish seem unaffected.)

Leptospirosis is another disease veterinarians see more often in warm-water years. The bacterial infection, which may affect the kidneys, is treated with penicillin or sometimes tetracyclines.

At TMMC, which is a research center, every animal that dies undergoes a necropsy to determine cause of death.

Johnson is studying whether some sea lions have a condition known as refeeding syndrome, a potentially fatal condition that may develop in starved mammals that eat too quickly. He is finding signs of lipemia (excess fats in the blood) and electrolyte imbalances, which can lead to seizures and death. The condition has not been documented before in rescued marine mammals, as no center has ever tended such a large population of starving animals at once.

Despite the medical attention, saving every animal is not possible, of course.

“Some have conditions so dire, so grave, they cannot respond to medical treatment and their organs will fail,” said SeaWorld’s Koontz. “They might only be with us for a day. It's ... tough on our rescue team. (But) they also know that without the care they provide, none of them would survive.”

At SeaWorld, Koontz said, about 65 percent of rescued pups are saved each year. Johnson gave a comparable estimate for TMMC — 60 percent.

Johnson considers those percentages remarkable, considering that many of the animals are near death when they’re picked up.

Gage said sea lions are the friendliest of pinnepeds and most amenable to training. That temperament helps them adapt to being captive, enabling them to survive starvation and recover to be released.

Their caregivers know they’ve succeeded when the pups become feisty, showing they can fight for food and take care of themselves.

“That’s what we want,” Koontz says. “When they come in, they are a bag of bones on death's door, and in about six to 10 weeks, they are plump, healthy and feisty.”

Once freed, the fate of the animals largely is a mystery.

“We have no way to determine how many survive once released, but very few, less than 10 percent, restrand,” Johnson said.

The percentage of those that recover following rescue this year won’t be known until the season is over, but Johnson anticipates it will be similar to last year.