Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

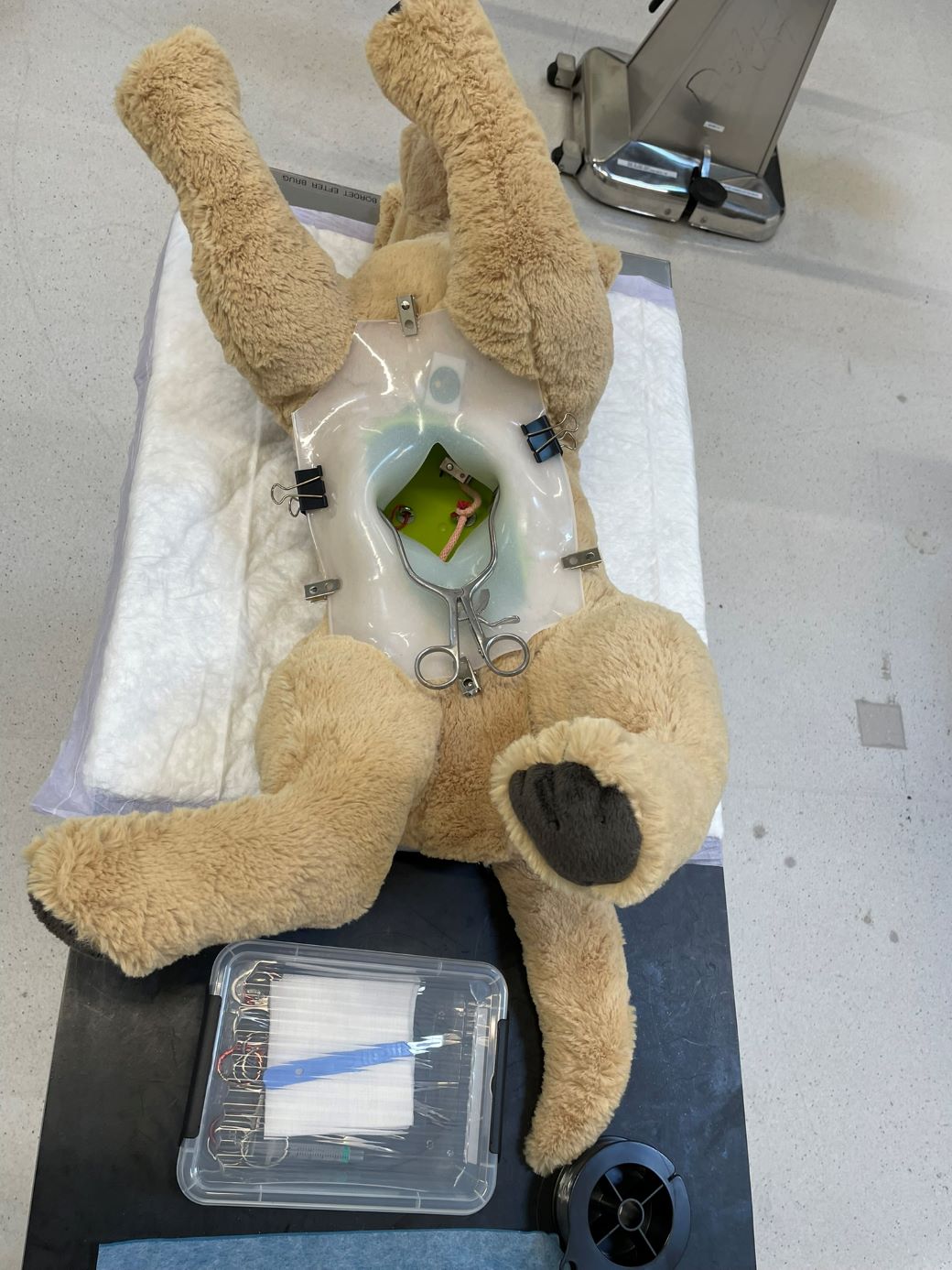

LMU_student_model_maker

Photo by Matthew Irvin

Emily Hale, a veterinary student at Lincoln Memorial University, forms bovine tongues and hard palates out of clay to cast into a silicone mold for veterinary teaching models.

This is the second of two parts. Read part 1.

Dr. Julie Hunt knows how to sew latex fabric, wield a Dremel grinder and mix and pour foam like a practiced crafter. Early in her veterinary career, she did not anticipate these skills would play a role in educating future practitioners.

Today, as the associate dean of clinical sciences at Lincoln Memorial University's veterinary school in Tennessee, Hunt oversees and sometimes joins two full-time makers who transform everyday objects, including knee-high pantyhose and plastic water bottles, into models for teaching clinical and basic surgical skills. (The nylons and bottles are used, with other materials, to create simulated scrotums for teaching bull castration.)

LMU's model-building studio, which Hunt describes as "Santa's workshop" and a "mad scientist's lab," has produced and validated in published studies more than a half-dozen different models, including one for learning how to draw blood from a cat and another for performing a cesarean surgery on ewes.

The use in veterinary education of simulations — models, manikins and task trainers made in-house or commercially — dates to the 1990s and has gained wide adoption in more recent years as established schools phased out and new schools never adopted the use of terminal surgery. Such surgeries are training procedures done by students on animals that end with the animals being euthanized rather than revived from anesthesia. Historically, veterinary surgical training relied on terminal surgeries and cadavers.

Now it is more typical for students to start their training using models of increasing complexity to learn techniques and cultivate dexterity and confidence before performing spay and castration surgeries on shelter dogs and cats. These are the only required surgeries on live animals for LMU students before their clinical rotations.

Even veterinary schools that still offer some terminal surgeries have robust skills laboratories built around hands-on task trainers.

Many of the early in-house model-making programs were developed from the ground up, pushed into being by one or two educators at a school who believed that using models was not a compromise over an animal in a terminal surgery but a means for improving veterinary training overall.

Even as models play a rising role, some educators believe the benefits are oversold and that nothing prepares students for surgery like operating on a living, breathing animal.

Toys R trainers

Early in her tenure teaching basic surgery skills at the University of Copenhagen in the early 2000s, Dr. Rikke Langbæk relied on lectures, textbooks and photos to prepare students for hands-on experience with a cadaver or live animal. She soon realized her students struggled to imagine performing surgery.

"So, I just brought in a toy animal, and then I showed them how to drape and how to prepare the surgical site," she said.

She saw immediately that the stuffed animals put students at ease.

Inspired, Langbæk then sliced the toys open to insert stand-ins for abdominal organs, vessels and other structures that she constructed from rubber bands, silicone tubes, examination gloves, sponges and balloons filled with water, air or flour.

Practicing with models enabled students to attain some proficiency without the emotional pressures of operating on a live animal, which she had seen could cause them to forget important little details, like securing the drape or ligating a blood vessel.

Being better prepared reduced students' anxiety and allowed the lessons to stick. The models had the added benefit of reducing the use of live animals for training overall, Langbæk said.

What surprised her early on was that a simulator didn't need to look "perfectly real" to aid students as intended.

Toy_model_UCopenhagen

Photo by Dr. Rikke Langbæk

For more than two decades, modified toy animals have been used as models for learning veterinary clinical skills at the University of Copenhagen.

"You have to look at the skill that they need to learn and figure out, what are the obstacles?" she said. "Is it difficult because it's slippery or because it's tough or because it's a very limited space? The simulator must be able to illustrate that."

However, she said, "I don't want to put the items into a cardboard box. I still want to place them in a toy animal ... for the narration, for the story and for the student to feel like a vet."

Langbæk also supervised master's degree students who created and validated the effectiveness of individual simulators, including one for canine cesarian sections and another for gastric dilation and volvulus, a life-threatening condition in which the stomach fills with gas and twists, leading to severe complications that require emergency surgery.

"I really wanted to make simulations for [emergency] procedures that the students need to know but they never get a chance to carry out during their education," she said.

By the time Langbæk retired this summer, she had created nearly 20 models for teaching clinical and surgical skills. During her tenure, models were integrated stepwise into a required basic surgery skills class. As of this year, they are available in a clinical skills lab where students can drop in and practice as desired, with guidebooks and videos for support. She is also a co-author of a guide to creating clinical skills laboratories written with educators at veterinary schools in Canada, the Caribbean, Germany and the United Kingdom.

Repetition plus feedback minus stress

On the other side of the globe, Dr. Dean Hendrickson imagined a place for simulations in veterinary medicine training while admiring movie special effects in the early 1990s. He thought, "If they can make it look so real in the movies, could we do something that would also feel and handle [like] real?"

Years later, as a veterinary surgery professor at Colorado State University, he became dissatisfied with the practice of teaching surgery through procedures in terminal labs or using cadavers. (This was many years before the program eliminated terminal surgeries, in 2022.)

"We were teaching procedures, not principles," he said. "We were teaching the students how to do a splenectomy, not how to do an 'ectomy.' And the reality was, in my world, 'ectomies' were the same."

The idea of special effects came back. Models, he believed, would enable instructors to focus on principles and create opportunities for students to practice basic skills, such as suturing and ligation (a procedure to close off a blood vessel or other fluid duct) over and over again.

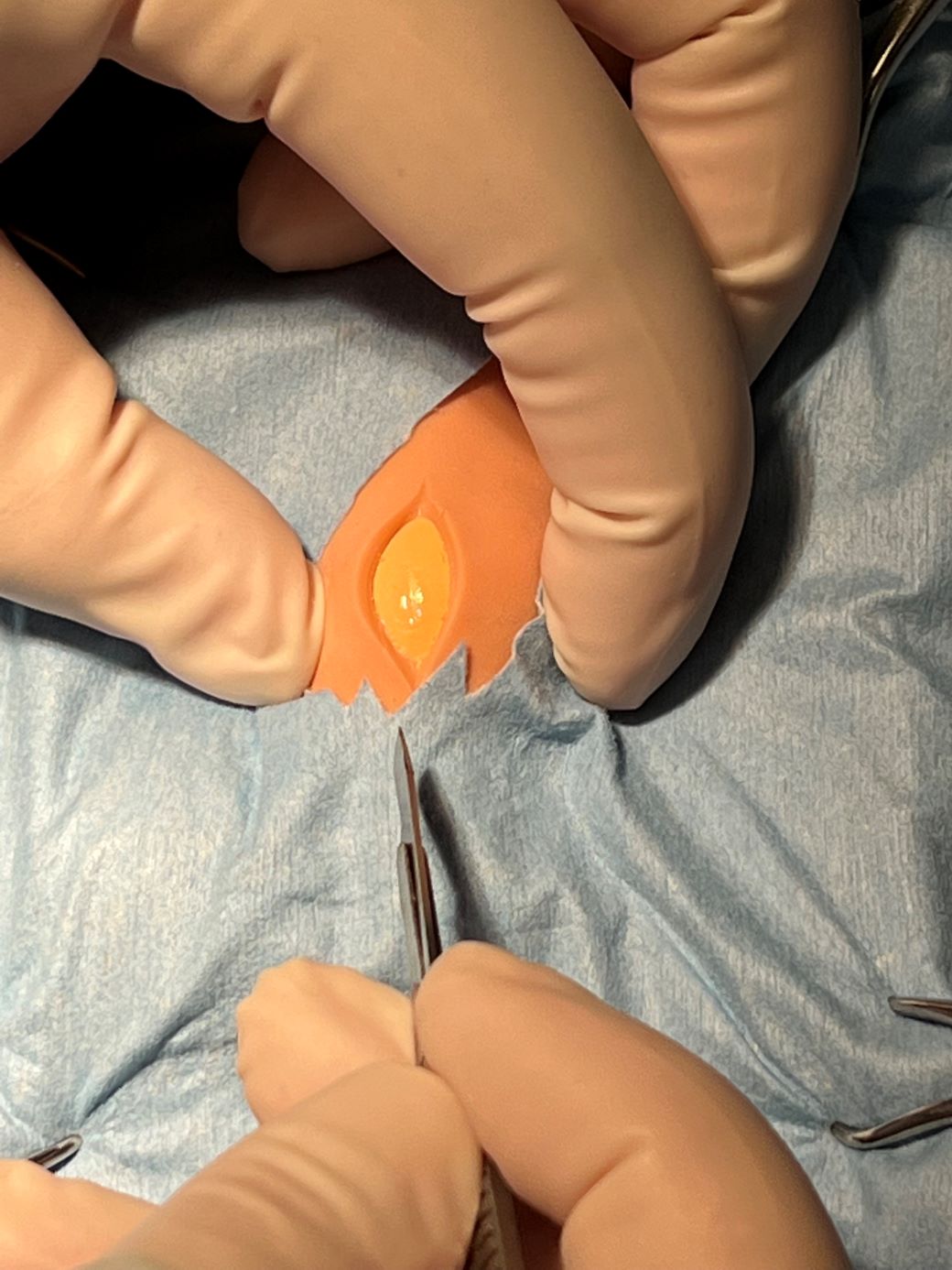

Incision_CSU

Photo by Dr. Dean Hendrickson

Using models made in-house, veterinary students at Colorado State University can practice making incisions for neutering a dog without the stress of cutting into a live patient.

"Students need more repetition with feedback," he said.

Hendrickson also saw that learning on models eliminated the high-stakes pressure of working with a live animal.

With a model, he imagined a student thinking, "Worst-case scenario, the air comes out of the balloon or the suture pulls out, and I take it out and do it over."

"There's so [much] less stress with that," he said, adding that students "can focus on getting great, as opposed to being nervous the whole time."

Hendrickson began assembling models in-house. The sideline caught the attention of the university's technology transfer people, who urged him to patent his inventions.

In 2012, he founded a company, SurgiReal, that makes products for the human medical and veterinary fields. Among its offerings are simulators for neutering a dog, a canine head with vasculature for practicing blood draws and inserting catheters, and a suture practice pad — a rectangular silicone pad that mimics the first five layers of an animal's abdominal wall. Another of its innovations, dubbed RealFlow, is a grid of liquid-filled vessels embedded in suture pads to mimic veins for drawing blood, suturing and ligation.

Hendrickson, who has nine patents now, said technology is expanding what's possible: "What we can do with silicone today versus what we could do 30 years ago is huge."

SurgiReal is one of more than a dozen companies selling scores of veterinary models around the world that range from simple analog trainers to models integrating computer technology, including haptics, which simulate the physical sensations of touch. The Haptic Cow, developed in the 2000s by Dr. Sarah Baillie, a veterinarian in the U.K., is a fiberglass model of a cow's rear end equipped with a robotic arm accessed through the rectum that fits on the student's finger and mimics the feeling of bovine internal anatomy, enabling students to practice virtual examinations and experience a semblance of the real thing.

Probably the highest fidelity models are produced by SynDaver, a Florida company that began selling a synthetic human cadaver in 2012, followed by a canine version in 2016. Made from a proprietary mixture of water, salts and fibers, the models feature replaceable bones, muscles, organs and vessels, can simulate bleeding and breathing, and be customized to mimic multiple diseases and conditions.

However, even as some models move toward ever-greater realism, Hendrickson concedes there is nothing quite like the real thing.

"[A]nimals are so amazingly well put together," he said. "They just are. But we can get close enough."

Moving away from models

Some surgery professors aren't sold on the idea that simulators, particularly more high-fidelity models, should play a major role in training veterinarians.

Dr. James Roush, a professor of small animal surgery at Kansas State University, has seen the use of models wax and wane at his program, where terminal surgeries were discontinued in the early 1990s.

"One of the problems surgeons have with models is that they are never close to real tissue," he said recently.

He pointed to his experience with a commercial bovine uterine prolapse model. "As an old dairy practitioner, I've tried them both myself, and the uterine prolapse [model] is nowhere near doing a real uterine prolapse in a cow," he said, explaining that the friability, or tendency to crumble, of actual tissue and real-world conditions of working with a live animal haven't been recreated.

After Kansas State eliminated terminal surgeries, some instructors incorporated commercial models, including one called the DASIE (Dog Abdominal Surrogate for Instructional Exercises).

Simulation in the spotlight

"They were essentially tubes of terry cloth and foam that the student could incise into, and depending on which model you bought, it was either empty, or it had a little latex uterus in it," Roush recalled.

According to Roush, the DASIE was OK for learning basic surgical hand skills, but "for experiencing what a live abdomen was, that was nowhere close," he said.

For a time, a veterinary technician created models for Kansas State's small animal surgery training program, including a seven-layer abdominal wall and organs for mock spay or neuter surgeries.

The mock surgery was phased out about six years ago, according to Roush. Now, the hands-on preparation that leads to a desexing surgery on shelter animals includes practicing how to drape a pillow, scrub in, suture muslin and latex and tie square knots.

Dr. Leslie Sprunger, an associate dean at Washington State University's veterinary school, which has a robust open skills lab, says models can't do it all.

"There just are some things still that we can't replicate in models," Sprunger said. "A living animal is just different than a model. The tissue feels different. They bleed in a different way than a simulated model can be made to do."

She added that models also generally can't capture variability. "Live animals are all different shapes and sizes," she said, "have more or less fat, are younger or older, even have random variations in things like blood vessel position and branching patterns."

Another limitation with models today is that not every animal is well represented. Several educators told the VIN News Service few large-animal-specific models are available.

A case for low fidelity

Dr. Julie Cary, who directs Washington State University veterinary school's simulation-based education program, was drawn to the field while working as a large animal surgeon and running the emergency rotation at the teaching hospital.

"Our students had some concerns about … whether they were going to be prepared for their live animal surgery labs," she recalled. At the same time, internal and national surveys were showing that veterinary students were struggling with surgery, she said.

In concert with students, Cary began trying new approaches, starting with expanded use of cadavers, then models. By 2011, they had established a voluntary skills lab equipped with various models and overseen by peer instructors. "It just slowly took over a life of its own," Cary said.

To validate the approach, Cary and team looked at the surgery performance of students who had access to the optional skills lab from their first year of study and compared it with the performance of two prior classes that had less and later access. The students who had more access spayed a live dog an average of 41 minutes faster and with fewer complications, as reported in a 2016 study.

With that, the skills lab gained the school administration's solid backing and ultimately became integrated in the core curriculum. "At the time, our dean was a scientist, and so we knew the way to his heart was data," Cary said.

Today, the simulation center occupies 11,000 square feet of space, having just undergone an $8 million renovation. Cary said some of the center's models are commercially made, but most are created in-house by self-taught builders and validated through internal studies.

Cary has drawn inspiration and lessons from the use of simulation in human health care, which she noted is 20 to 30 years ahead of veterinary medicine. In 2019, Washington State became the first, and is still the only, veterinary-specific education program certified by the Society for Simulation in Healthcare, which provides continuing education and certification predominantly for human health care programs, particularly nursing.

WSU_sim_lab

Washington State University photo by Ted S. Warren

Washington State University's simulation-based skills lab includes a variety of task trainers, such as this dog head for practicing intubation.

Lagging in the field has been beneficial to veterinary medicine, Cary said, in that it's been able to learn from human medicine's experience. For example, higher-fidelity models have been found to be not necessarily better than lower-fidelity ones, she said, citing research showing the use of technologically advanced models with fancy electronics caused student practitioners to regress in their skills.

"I looked at that as good news, because I don't know that we'll ever get as advanced as what they have," she said.

Supportive community

Educators involved in making models often use the word "fun" when describing their work. They are also glad to share what they've learned with other programs.

That's what educators at Atlantic Veterinary College (AVC) at the University of Prince Edward Island in Canada found.

AVC is in the early days of developing an open skills lab. It started with commercially produced suture pads and the DASIE model, according to Dr. Stephanie Landry, the school's clinical skills coordinator.

Landry said they found some commercial models weren't always anatomically correct; others were too expensive. So, they've focused on building their own.

Last September, Landry and Melissa Hamel, a veterinary technician and a potter involved in making models, attended the International Veterinary Simulation in Teaching (InVeST) conference to expand their knowledge.

InVeST was founded in 2011. The group hosts semi-annual conferences. The next is at Texas Tech University in October. During conferences, educators and model makers present papers, run workshops and generally share what they've learned.

"What we discovered is that small groups of really creative people spearhead movements to try to develop the model and simulation programs at different colleges, and they just work from the ground up and help build the program," Landry said.

Another source of support for Landry and her team is an online forum where people share their experiences with model creation. It's where AVC got the idea for its current spay model.

Landry said one of AVC's goals is to get input from students and help them eventually create models on their own.

If Hunt's experience at LMU is any measure, they'll have no problem.

She said she's had good luck recruiting students to help build and validate models during summer term.

When she recruits prospective candidates, she says, "If you like arts and crafts, then this is a job for you, but if you like micropipetting and ELISA [lab tests] and that kind of stuff, you need to go to a different job."

Their response? "Most of them are like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is amazing. I love it.' "

Part 1: Terminal labs: Controversial veterinary teaching method ebbs