Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

Kansas State student

Kansas State University College of Veterinary Medicine photo

Spaying and castrating shelter animals has become a standard way veterinary students gain experience in live animal surgery. Kansas State University College of Veterinary Medicine adopted that approach and eliminated terminal labs in the early 1990s.

This is the first of two parts. Read part 2.

When she was a veterinary student, Dr. Meghan Shannon was heartsick at the prospect of learning surgery by operating multiple times on a dog that didn't need it, then ending its life intentionally.

Being at a school in the southern United States, Shannon already felt like an outcast as a vegan Northerner sporting a crew cut and nose ring. So she didn't hesitate to openly question the practice.

"I couldn't understand why we were supposed to accept just using an animal and discarding it as part of our learning," she said. "It didn't seem like something we should be doing as veterinarians."

The school excused her from the lab, allowing her to work on a cadaver instead and read some surgery reports.

Shannon graduated 25 years ago. She thought terminal surgeries in veterinary school were a thing of the past by now, considering society's rising regard for animal welfare. She was therefore astonished recently to see the subject raised in a veterinary chat group by a current student who is trying to persuade her school to eliminate what are known variously as live-terminal laboratories, terminal labs, terminal surgeries, nonrecovery surgeries or nonsurvival surgeries.

A historically accepted way of teaching surgical skills, terminal labs have been abandoned by many veterinary schools — decades ago, in some cases. Schools founded in the past 25 years in the U.S. have never used terminal surgery at all. Instead, they've embraced the use of models, whether simple task trainers concocted with materials from a hardware store or lifelike reproductions composed of state-of-the-art materials, to teach students clinical and surgical skills.

From there, students progress to operating on animals who live on after the lesson is over — typically spaying or castrating dogs or cats from nearby shelters and caring for them through recovery like regular patients.

The same approach has become standard at older schools, too. But at least a few programs still offer elective labs in live animal surgery that end with the animal, usually a livestock species, not being awakened from anesthesia.

The practice is one that veterinary educators are, by and large, uneasy discussing publicly because of concerns that the subject will draw notice from animal rights activists or other unwelcome attention, potentially extending to threats and violence. Even those at schools that have disavowed terminal surgeries tend to shy from the topic, some because they don't wish to be perceived as critical of fellow institutions.

The message that caught Shannon's eye was posted by Larrea Cottingham, a student at Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine. During her second year in the four-year DVM program, Cottingham learned about an elective course for third-year students involving terminal procedures on goats and horses.

Dismayed that students would "kill your own patient for your own learning," as she put it, Cottingham sent a survey on the subject to everyone on the school listserv — students, faculty and administration, about 700 people. She asked students whether they knew that the course involved terminal surgeries and invited their thoughts.

The survey generated heat, though not in the way Cottingham anticipated. The administration didn't object to her raising the issue, but many students did. They didn't want the course to be eliminated.

Dr. Leslie Sprunger, an associate dean at the veterinary school, said she respects Cottingham's efforts and called her position "philosophically valid." Sprunger is sympathetic, as well, to those who want the course maintained.

"Students who are objecting to the idea of taking out those remaining terminal labs are doing it from the basis of wanting to feel like they have [learned] the best level of skills and competencies that they can," she said. "Nobody wants to be the person that [after graduating] inadvertently does something bad in surgery that's going to cause harm to another animal."

From an educational standpoint, the purpose of teaching students on live animals "is to help them learn things that are difficult for them to learn or fully appreciate on a cadaver or a model or from a textbook," she said. "That has always been the intent."

Here's the nub: "Our views of what can be effectively taught with a resource other than a live animal have changed dramatically over the last 50 years," Sprunger said.

Evolving thinking

Like many long-timers in academia, Dr. James Roush experienced the change firsthand. He remembers as a veterinary student in the early 1980s operating on one dog three times. He and his classmates first practiced closing wounds, giving the animal a week to recover. Next, they performed an ovariohysterectomy, or spay surgery. Following the dog's second recovery, they performed an invasive procedure — an intestinal anastomosis — after which the animal was euthanized.

No one questioned that method of learning at the time, Roush said.

Later as a board-certified surgeon, Roush joined the faculty at Kansas State University's veterinary school, where a different tack was introduced in the early 1990s: Students spayed and castrated shelter animals that would go up for adoption. To prepare for the live surgeries, the students practiced skills like tissue handling and suturing on inanimate models.

"It was a different teaching approach," Roush said, explaining that, "It was previously thought that, 'Well, you're doing the actual procedure, you'll get it,' as opposed to, 'We're going to go stepwise and work on the surgical techniques of the procedure.' "

To assess their abilities, faculty assigned students to perform an operation they hadn't done before, using a cadaver. They found that the students whose live surgery experience was limited to desexing operations but had focused on technique did better than those who'd done multiple types of operations in terminal labs.

"In other words, doing all those various procedures didn't help them do a new procedure," Roush said. "At that point, there was no going back."

Terminal surgeries at Kansas State became a thing of the past.

Similarly, the veterinary school at Tufts University in Massachusetts eliminated terminal surgeries in 1994, a shift propelled by students, as described on the school's Animal Use in the DVM Program webpage.

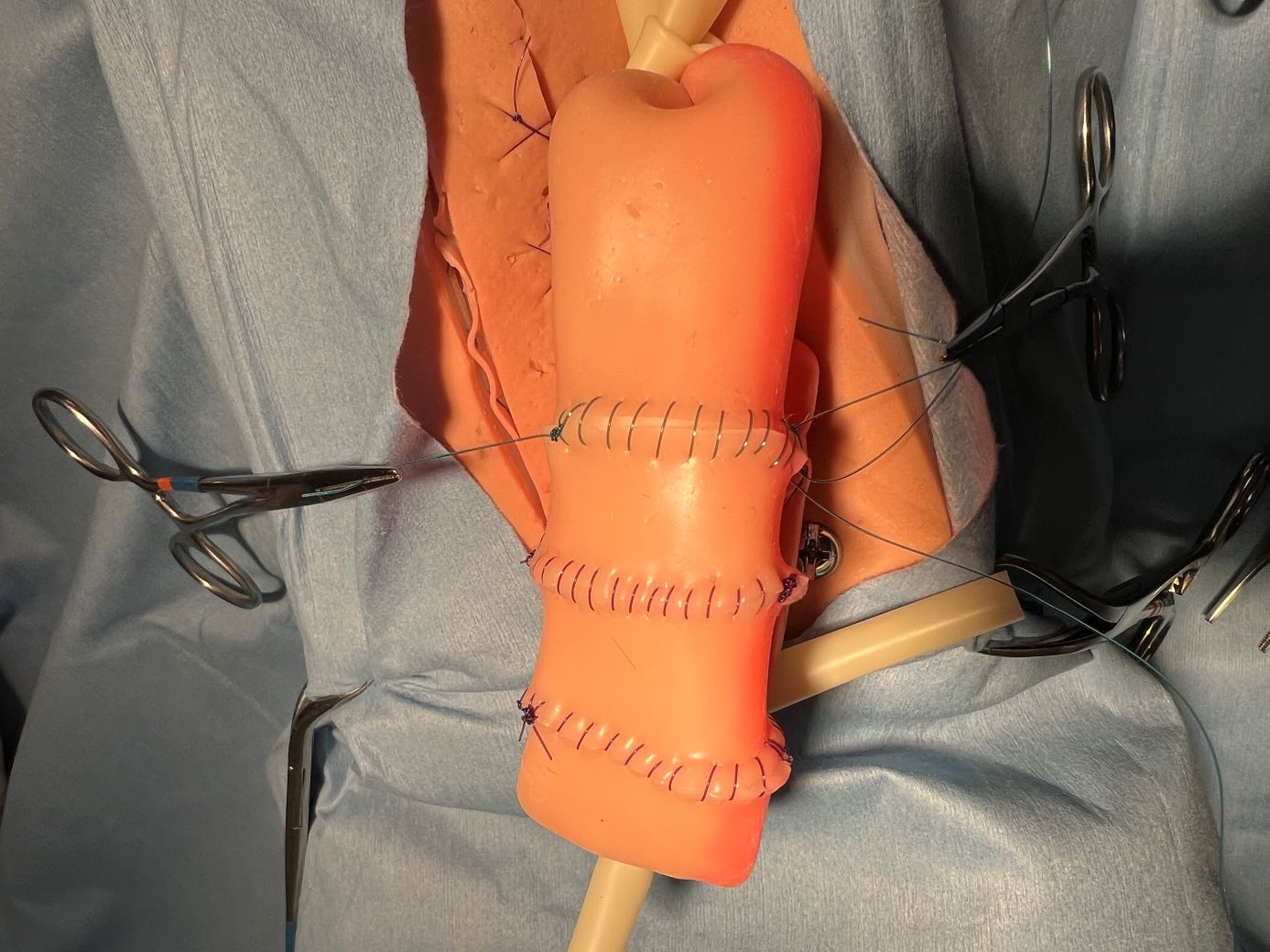

small intestine resection

Photo by Dr. Dean Hendrickson

A silicone-based form provides a model on which students may practice the delicate art of connecting hollow tubular structures, simulating resection and anastomosis of the small intestine.

By then, as public regard rose for animals, especially household pets, the practice had become controversial nationwide, though still entrenched. A survey of veterinary schools in the U.S. and Canada found that terminal labs were used in more than two-thirds of programs, according to a paper published in 1993 in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. In more than a quarter of the schools, animals were not recovered from anesthesia in every teaching laboratory. (The findings were based on the responses of 27 schools out of 31 solicited.)

In the early 2000s, terminal surgeries seemed on the way out. The sense that they might be outdated was captured by the title of a panel discussion at the AVMA convention in 2003: Are Live-Terminal Laboratories Necessary?

The answer was a firm "no" at a school that opened in California that same year.

From its founding, Western University of Health Sciences' veterinary program adopted a "Reverence for Life" philosophy in which it declared that "animals will not be harmed in this curriculum."

Since then, seven more schools have been established in the U.S., none using terminal labs in their curricula.

The VIN News Service obtained information for this report through a combination of direct contacts and a survey that the American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges agreed to distribute to its 59 member institutions around the world, 36 of which are in the U.S. To encourage participation, VIN News informed survey recipients that their responses would be reported only in aggregate and not by individual institution.

The survey, distributed in July, elicited 13 responses. VIN News obtained information on another 11 schools through direct inquiries, for a total of 24, equaling 40% of AAVMC members globally.

Of the 24, seven reported having terminal labs, all elective.

Task force indirectly rejects the practice

In 2021, the AAVMC formed a task force to write guidelines on the use of animals in veterinary education, producing a two-page document in 2022, followed by a 64-page handbook that expands on the guidelines.

While addressing the uses of cadavers and live animals, neither document directly references terminal surgeries.

That omission has meaning, according to the task force chair, Dr. Julie Hunt. Speaking as an individual and not for the task force as a whole, Hunt said, "The guidelines are 'This is what we think you should be doing,' and the handbook explains 'This is how you could meet the guidelines.' "

The guidelines say that schools should "proactively work toward reducing invasive procedures to those that have the potential to benefit the health and welfare of the animal."

At the same time, the task force implicitly acknowledged that eliminating such surgeries might be considered infeasible in some contexts.

Hunt, who is associate dean of clinical sciences at Lincoln Memorial University — a newer school where terminal labs have never been used — said the panel opted not to say that schools should work on eliminating such procedures because "There are potentially some invasive procedures, particularly in large animal work, where there are not models developed to replace those procedures, as yet."

Devising alternatives

Tufts' borrowed heifers

Tufts University photo by Jeff Poole

Heifers borrowed from a regional dairy by Tufts University Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine provide students a way to perform surgery on large animals for the animals' benefit. The school ended its use of terminal labs in 1994.

Programs forgoing terminal labs even in livestock species have found workarounds, though. At Tufts, for example, a dairy provides heifers to the veterinary school for a year, according to the dean, Dr. Alastair Cribb. During that time, students in a large animal surgery elective perform on the heifers a prophylactic omentopexy, a procedure in which a compartment of the stomach called the abomasum is sutured to prevent displacement and twisting, a painful and potentially life-threatening condition.

The school also impregnates the heifers using artificial insemination, enabling students to follow the pregnancies and learn rectal palpation skills, Cribb said.

At St. George's University on the Caribbean island of Grenada, the veterinary school works with area farms, sending students to provide services such as castrations on pigs, sheep and goats, according to the school's head of surgery, Dr. Rodolfo Bruhl Day, who did away with terminal procedures there when he joined the faculty in 2008.

"We organized the labs in a way that we're going to render a service to the community. It's a quid pro quo," Bruhl Day said: Animals in the community get free veterinary attention while students get needed clinical experience.

New Zealand's only veterinary school, at Massey University, ended its terminal labs more recently, in 2022, according to the school's head, Dr. Jon Huxley. Several elements converged to spur the change.

One is that support staff and students alike were voicing discomfort with the practice, Huxley said. Among employees, he explained, "There is a burden carried by everybody involved in a class like that ... from the most senior clinicians through to the support staff. ... It was a big team effort."

Fortuitously, the school was undergoing a major facilities renovation, providing an opening to establish a clinical skills laboratory stocked with a wide range of low- and high-fidelity models.

The prospect of losing surgery experience in livestock wasn't an issue, Huxley said. Being in a country with a large ruminant farming industry, students on their clinical rotations may do cesarean sections on sheep and cattle.

Study tallies animal cadaver and

terminal surgery use in schools

Hunt, who chaired the AAVMC animal use task force, noted that not only have other countries renounced terminal surgeries, some — notably the United Kingdom — effectively prohibit them.

"There's quite a difference internationally, and we're not a leader," she said.

In the U.K., the use of animals for educational purposes, including the use of anesthesia on any animal except for its own benefit, is governed by the Animals Scientific Procedures Act of 1986, according to Christine Nicol, a professor of animal welfare at the Royal Veterinary College.

"Any veterinary school wanting to conduct surgery purely for teaching purposes would have to obtain a license and comply with very extensive conditions and, as far as I know, this has never happened in the context of standard clinical veterinary training," Nicol said.

Medical schools in the U.S. and Canada also no longer use live animals in core or elective courses, according to Dr. John Pippin, director of academic affairs at the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, an advocacy group. He said the last to forgo the practice were Johns Hopkins University and the University of Tennessee-Chattanooga in 2016.

Students defend the labs

At Washington State, more students sign up for the course that involves terminal labs than can be accommodated. Dalton Gibbs, a fourth-year student who took it last spring, called it "the most valuable course" of his veterinary education because it encompasses mock client communications, animal care, anesthesia, surgery and discussion of euthanasia, "which is something we don't do often in school," he said.

Absent the labs, Gibbs said his live surgical experience in school might be limited to a single spay. "I don't feel like it's enough for me to go into practice confident with surgery," he said.

During fourth-year clinical rotations, students may be present for live surgeries but not necessarily handle tissue or even instruments, he said.

Hayden Erickson, another student who took the course last spring, noted that in the labs, "You run the show. You're either the surgeon, you're the assistant or you're the anesthetist."

As for the animals whose lives end in the lab, Erickson, referring to one of the animals he operated on, said, "With what I learned from this pony, I can take that knowledge ... and be able to treat and help so many more patients in the future."

At Colorado State University, it was mostly students who hadn't taken terminal labs but hoped to who objected vigorously when their veterinary school administrators decided to eliminate the labs in 2022.

"Veterinary students don't like to not have the same thing the students had before them," said Dr. Dean Hendrickson, who described the pushback as "a blood bath."

Hendrickson was one of several surgery faculty members who oversaw terminal labs, but long before Colorado State changed direction, he believed there was a better way to teach surgery.

As a student nearly 40 years ago, Hendrickson took many terminal labs himself and accepted the "ends justify the means" view. Then, early in his teaching career, he observed that assigning progressively more complicated and invasive procedures over a few days or weeks did not serve students well.

"They're not prepared," he remembers thinking. "They're going from all-theoretical to very involved surgery."

He mused that a more methodical and effective method of teaching would be to emphasize not procedures but principles, using simulation to introduce concepts and build skills.

While still overseeing terminal labs, Hendrickson began assembling models as teaching tools, for example, using balloons filled with air or water to teach ligation, a procedure to close off a blood vessel or other fluid duct.

By the time Colorado State dropped terminal procedures, Hendrickson was all in. Soon, he said, the students were, too. After day one of the first non-terminal lab series, his students not only were visibly relaxed, he reported, they were grateful — including former skeptics.

"Every single one of them ... said, 'Thank you,' " something Hendrickson said had never happened before because with terminal surgeries, "They were so wrung out after that first day of live-animal work, they just stumbled out of the lab."

'Justifiable' but 'not essential'

Today, learning on models and performing their first live surgeries by desexing shelter animals has become the customary way that students begin acquiring surgery skills, regardless of whether their school maintains terminal labs.

At Washington State, for instance, Sprunger said students are expected to practice on models with supervision and feedback and to demonstrate that they have the basics down before operating on a live animal.

Reflecting on the school's continued use of terminal surgeries, Sprunger said animals obtained for the course are diverted from slaughterhouses and, sometimes, come from research programs in which they would have been euthanized at the study's end.

"If we have animals that are not going to continue living on the planet regardless of what we do, if we can obtain some educational value in a humane way for a brief period of time before those animals are killed, then I am philosophically comfortable with that," she said. "We're not purchasing animals that would otherwise be going back out on the range."

That said, Sprunger noted that the majority of WSU veterinary students don't take the lab and nevertheless "become competent veterinarians."

"Right now, we take the position that it is a justifiable investment and a justifiable use of animals, based on how we take care of them, and that it's a good enough experience for the students who can take the course that it's worth continuing," she said. "It's clearly not essential to the training of a veterinarian, because two-thirds of our class don't have this experience."

Will the school ultimately forgo terminal surgeries altogether? Sprunger, who is retiring this fall, said she could not predict. Whatever happens, she said, it will not be determined solely by the administration nor driven by student sentiment one way or another.

Rather, curriculum decisions are made by faculty consensus and should be based on up-to-date evidence about teaching techniques and learning, she said, noting: "The curriculum is always evolving."

Part 2: Models take an expanding role in veterinary training.