!This story has an important update.

Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

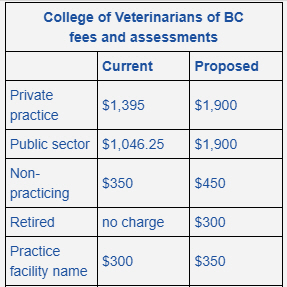

College of Veterinarians of BC

fees and assessments |

| |

Current |

Proposed |

| Private practice |

$1,395 |

$1,900 |

| Public sector |

$1,046.25 |

$1,900 |

| Non-practicing |

$350 |

$450 |

| Retired |

no charge |

$300 |

| Practice facility name |

$300 |

$350 |

| Accreditation inspection (initial) |

$850 |

$1,100 |

|

Prices are in Canadian dollars and exclude general sales tax. The fees shown are a selection. For a full rundown, see existing fees and proposed fees.

|

Veterinarians in British Columbia have a tough decision to make by the end of this week about the regulatory fees they must pay to practice in the Canadian province.

The provincial regulatory body for the profession, the College of Veterinarians of British Columbia (CVBC), is asking them to approve a 36% hike in their annual registration fee to CA$1,900 (US$1,374), among a raft of other fee increases. If the increases are rejected, the college says it will become insolvent, potentially prompting the government to step in and allow the college to raise fees without veterinarians' blessing.

In an unusual protocol among Canada's provincial veterinary boards, British Columbia gives its more than 2,000 practitioners authority over proposed fee changes. The last fee increase occurred in 2011; the annual registration fee has remained at CA$1,395 for the past 14 years. (All fee figures quoted in this story exclude applicable taxes such as Canada's 5% general sales tax, or GST).

British Columbia's government already has demonstrated a willingness to intervene. In April, it mandated that veterinarians in the province each pay a one-time CA$500 special levy (plus GST) to help keep the CVBC financially afloat.

Now the CVBC is asking to raise fees overall. In addition to the annual registration fee, for example, it would raise the fee for the provincial entry exam that all new graduates must take — to CA$450 from CA$350. Other fees affected include those for registering a new practice name or having a practice inspected for accreditation. A complete list of proposed fees is posted online.

The proposal was announced on July 28, and veterinarians have until Friday (Aug. 29) to cast their vote. If approved, the new fees take effect Oct. 1.

The CVBC's push comes after it accumulated a deficit of about CA$1.2 million over two years, which, it said, puts it on track to become insolvent by May 2026. The college has blamed the red ink on the prolonged lack of fee increases combined with a surge in demand for its services.

"The demands of the college in the past fiscal year broke various records …." its registrar and CEO, Christine Arnold, said in the organization's 2024 annual report. Arnold cited an unprecedented number of complaints about veterinarians and associated disciplinary hearings. She also cited a rise in "emergency responses required to address immediate risks to public health or safety," without elaborating.

The CVBC maintains that veterinarians have rejected proposed fee increases three times since 2011 — in 2012, 2019 and 2023 — and that Canada's total inflation rate (based on its consumer price index) has risen 38% since that time.

CVBC annual reports show it booked a deficit in the year ending June 30, 2024, of CA$680,600, adding to a deficit in the 2023 financial year of CA$495,600. During each of the four previous financial years, it booked a surplus, amounting over that time to CA$1.086 million in total.

The CVBC doesn't say in its annual reports why it thinks complaints against veterinarians have risen, and it didn't respond to questions from the VIN News Service.

In an official response to the fee proposal, the Society of British Columbia Veterinarians (SBCV) — a chapter of the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association, which represents practitioners — is critical of the CVBC's financial management. However, the SBCV is urging its members to vote in favor of the fee hikes because it worries the government will intervene if they reject them.

The SBCV maintains that the CBVC wants the government to eliminate veterinarians' sway over fee decisions, which it contends will leave the CBVC to raise fees carte blanche. "The SBCV feels that without sound governance and strong financial management, such unfettered discretion could be disastrous for the profession, farm animal production, and the animal-owning public," it says in the official response.

The SBCV takes issue with the CBVC's assertion that veterinarians have rejected a fee increase three times since 2011, noting that in 2023, the CBVC didn't hold a vote but polled registrants to determine how they would vote. And when the CVBC asked for a fee increase in 2019, it maintains, the college's finances were in far better shape.

Corey Van't Haaff, the SBCV executive director, said the organization was taken off guard by the sudden deterioration in the college's financial position.

"We would have preferred to have had a really strong grasp of what their situation was before it got to this point," she said in an interview. "The threat of insolvency requires immediate action, and it doesn't give people a chance to discuss and to try to develop other solutions."

Van't Haaff said the SBCV would have preferred to see fee increases every one or few years based on the inflation rate. She acknowledged she couldn't predict whether veterinarians would approve such increases. "What I can tell you is that veterinarians are very sensible, science-based people, and if you educate them why you need the money, you certainly improve the likelihood of them saying yes."

The SBCV has expressed concern about how the CVBC approaches complaints against veterinarians and is working on possible solutions to the college's funding crisis that it plans to present to the British Columbia government.

"Why are there more complaints?" Van't Haaff asked. "Is there something the regulator can do to educate veterinarians so they don't attract certain types of complaints or to ensure that the public understands the complaint process? More importantly, is there a way of handling complaints and their investigation procedures that doesn't cost quite as much?"

The CBVC's reputation for handling complaints took a hit in 2015, when British Columbia's Human Rights Tribunal found that it had racially discriminated against Indo-Canadian veterinarians by unfairly accusing them of providing substandard care.

A report by an independent consultant, Harry Cayton, that was commissioned by the CBVC and published in June found the ruling in 2015 still haunts the college because it has "struggled to restore its credibility and effectiveness as a regulator" and "seems to have been paralysed by uncertainty and self-doubt."

In 2021, the CBVC commissioned a review of its complaints process and is still working through the recommendations in that review. Related improvements to the college's complaints-handling process "came expectedly at a material cost," its treasurer, Gian Sihota, says in its 2024 annual report.

The CBVC maintains — as does Cayton — that British Columbia's Veterinarians Act limits the college's ability to regulate practitioners effectively and efficiently in the public interest.

"The act requires almost every decision of any materiality to the mandate of the CVBC to be approved by a majority of voting registrants," it said in a memorandum sent last year to British Columbia's agriculture minister. "This framework is antithetical to the core responsibility of a professional regulator, being the protection of the public even where, and arguably especially where, the carrying out of that objective is contrary to the registrants' self-interest."

Van't Haaff said if veterinarians were to lose their oversight of pricing decisions, the SBCV would like to see an alternative check placed on CVBC pricing proposals, such as the appointment of an independent administrator or superintendent. "We currently have a good check and balance here, and if it's lost, we need an equally effective one," she said.

Update: The proposed fee increases were approved, with 55.4% voting in favor and 44.6% against, the CVBC said in a statement on Sept. 2. Of 2,595 eligible registrants, 36% voted.