Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

Photo courtesy of Randall Ruble

A veterinarian for nearly 50 years, Dr. Randall Ruble only recently began to reflect on the adaptations he made in his work to navigate colorblindness.

When Dr. Randall Ruble attended veterinary school in the 1970s, being colorblind wasn't at the forefront of his mind. He pursued his studies with the merest of help and adapted as needed to visual challenges in his clinical practice.

Only now, late in his career, is the small animal practitioner in Central California beginning to appreciate how color vision deficiency — not seeing colors in the same way others do — influenced his life.

Ruble has red-green color vision deficiency, which makes it difficult to distinguish between red and green hues. Usually genetic and affecting males more than females, it is the most common form of colorblindness, according to the National Eye Institute. A less common form is blue-yellow deficiency. Those with the rarest form see no colors at all. People who are colorblind lack some or all of the cone cells in their retina that enable them to perceive color.

There always have been veterinarians with colorblindness, but for those like Ruble, it has been a mostly private affair.

Ruble graduated from the University of California, Davis, in 1976 and completed an internship in small animal medicine at Oklahoma State University. He owned a companion animal practice in the San Francisco Bay Area from 1983 to 1994. After selling the practice, Ruble earned a master's in preventive medicine and a doctorate in comparative pathology and worked in laboratory animal medicine for a decade. He has since returned to clinical practice.

He talked to the VIN News Service about his experiences to raise awareness and spur support for aspiring veterinarians and practitioners with color vision deficiency.

The following interview is edited for length and clarity.

Let's start with terminology. I understand people use different words to describe color vision deficiency. What word or words would you use to describe how you see colors?

As I was born in the United States and grew up in the U.S., I use the term "colorblindness," but if you go to South America, it's more commonly referred to as Daltonism. There was a guy, I think it was in the 1700s, that wrote about red-green colorblindness, and so Daltonism specifically [refers to] red-green colorblindness. My grandson has a colorblindness that is more focused on yellow colors.

When and how did you first discover you perceived color differently from others?

When my mother put a plate of noodles on the table, and I said, "I don't wanna eat green noodles." My father and my mother looked at each other and said, "They're not green, they're brown." [I was] probably about 8 or 9 years old.

Did being colorblind influence your choice of a career?

Absolutely. My father was an electrician, and I probably would have followed in his footsteps except that I can't tell a red wire from a black wire, and I can't tell an orange wire from a green wire, and that's a really big drawback for an electrician.

I ended up getting a job in a veterinary hospital cleaning up in the afternoons, and it kind of stuck.

You've said being colorblind in veterinary school wasn't easy for you. What subjects posed an obstacle and why?

Histopathology and hematology were the two biggest problems. In histopathology, you're using a stain called H&E, hematoxylin and eosin. It colors things red, and it colors things purple and blue. If you can't tell blue from purple, you're at a big disadvantage. So, yeah, histopathology was a real bear, and I got no extra help there.

But when it came to hematology, Oscar Schalm was absolutely fantastic. He would spend, I'm going to say, at least half an hour to two hours per week personally tutoring me. If it weren't for his help, I doubt I would have passed the course.

This was a professor you had?

Yeah, he's world-renowned. He wrote one of the seminal textbooks on hematology.

Were there any other accommodations or supports for you in veterinary school?

Nope. His personal tutoring was about it.

What was it about hematology that was challenging?

What was and still is challenging about hematology is that much of it relies on subtleties of color. As an example, there are different types of white blood cells — neutrophils, eosinophils [and] basophils — which are different types of granulocytes. They are differentiated by the color of their granules within their cytoplasm. Basophils have blue granules. Eosinophils have red granules and neutrophils have pink granules. For a person with Daltonism the difference between red and pink is very subtle. This is true for dogs and cats, and then you get into other species such as rabbits, which have granulocytes called heterophils which can be shaded red to pink. In birds, the granulocyte colors vary by species, thus, they can be pink, orange, red or brown — or so I have been told.

After graduating, what aspects of practice were most affected by your colorblindness?

In clinical practice, it's kind of hard to tell what color the skin is if it's inflamed. Oftentimes, I miss the pinks and the reds of skin inflammation, whether it is on a belly or down an ear canal. Looking down inside the ear canal of a dog with an otoscope to evaluate an ear infection is challenging.

If a dog has inflammation on the abdomen from allergies, most of the time I miss that pink color.

None of this did I realize in the first decade of practice. I realized it more looking back: I missed this and I missed that. It would be, I think, advantageous if the profession could find out who has it, and then work with them to find ways around it. But I don't think that they should be prohibited from joining the profession.

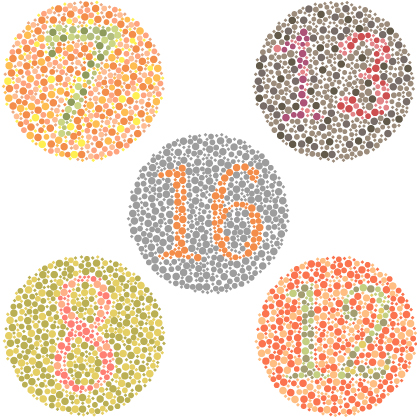

Ishihara Test

Adobe Stock image by eveleen007

The image shows examples of Ishihara plates, which comprise a classic test for red-green colorblindness. The plates feature a foreground figure in one color against a background of another color. The colors are chosen specifically to have enough contrast for someone without color vision deficiency to identify the foreground figure, but an insufficient amount of contrast for those with red-green colorblindness. Starting in the top left of this image, the numbers featured are 7, 13, 16, 8 and 12.

With those conditions that were harder for you to detect, how did you adapt?

Currently, I practice with a younger graduate ... and she relies a lot on cytology of the ear. I don't use it because I can't see it. So, you learn to not do things that don't have a benefit and they become, I don't want to say a waste, but they're not a good expenditure of your time.

Same thing on aspiration of lumps. Most people will use H&E stain, Wright's, Diff-Quik. I tend to use new methylene blue, which just gives you a monochromatic coloring of various shades of blue. A way for a histopathologist to get around the problem would be to use silver stains, which are various shades of gray.

In an email, you mentioned one particular advantage that you found. Can you tell me about that?

It seems that I can pick up icterus or the yellow color [in skin, gums and in the whites of the eyes] when animals have either liver problems or red blood cell hemolysis. In my personal life, where I found that to be an advantage was with my oldest daughter. When she was born, soon after birth, she developed icterus from a red blood cell issue, and I was able to see the color before her mother or before anybody else could spot it.

During your career, were you aware of other veterinarians who also had colorblindness?

Yeah, there was at least one other guy in my class who was colorblind, and Dr. Schalm used to spend time with him also. I can't say that we ever chatted about it, though. It's one of those things where you don't end up talking to people about it [in general], because if you don't have it, you can't understand it.

You have said that after nearly five decades as a practitioner, you only recently began to appreciate how much colorblindness challenged you in veterinary school and later in practice. Why do you think it took so long to sink in?

I think it was a matter of, when I got out of veterinary school, I was married, soon after there were children, and so life was always a scramble just to keep up with things. And now at this point in life, I've got time to sit back and reflect.

Now that you've had some time for reflection, what can veterinary medicine as a profession do to ease the challenges for veterinarians with colorblindness?

One thing that I think would be a help is asking after admission — not before admission, but after admission — "Are you colorblind? Do you need some extra help?"

What advice do you have for those who have colorblindness and aspire to become veterinarians?

Don't let it inhibit you from choosing the profession. And then ask for help.

When I went to veterinary school, I didn't know who to ask, and they were throwing stuff at you so fast, I never even thought about asking for help.

Are there any presumptions you encounter about colorblindness that are incorrect?

If you tell people you are colorblind, then they start wanting to hold up, "Well, what color is this? What color do you see?"

People don't really realize what an individual thing color perception is. Maybe it's a model for everything in life: Everything is individual perception.