Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

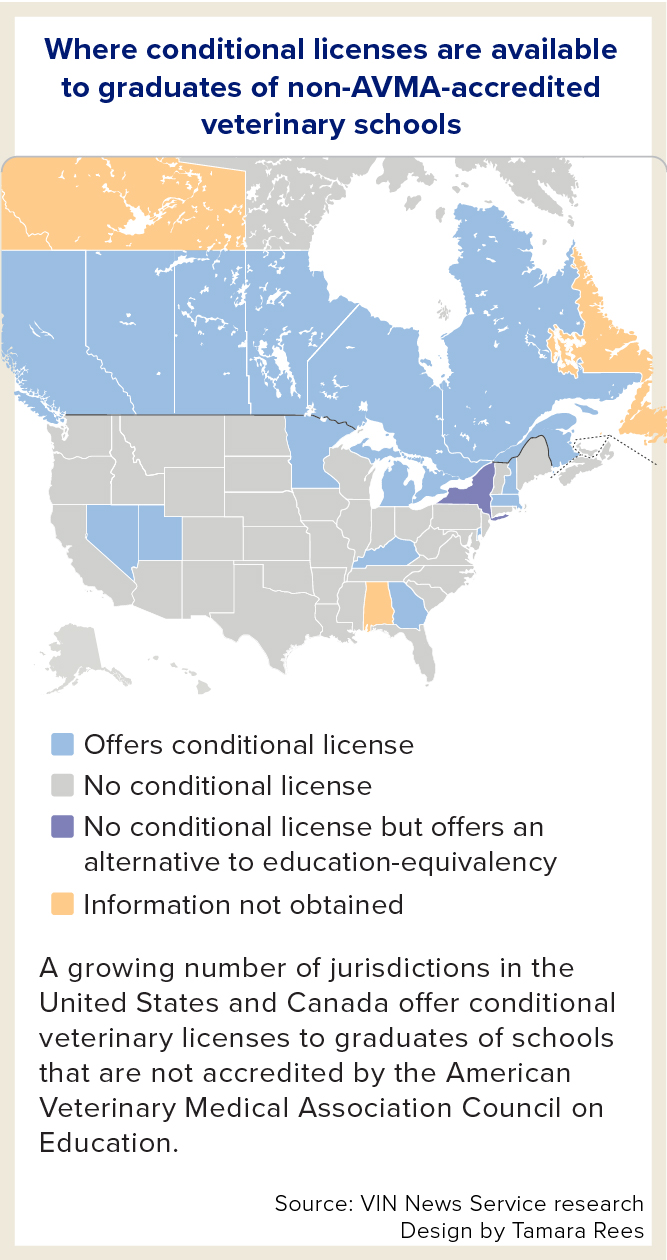

Conditional_licensing_map

Recruiting veterinarians to New Hampshire is tough. It's why state lawmakers last year created a conditional license for foreign-trained veterinarians.

They had two types of practitioners in mind. The first are graduates of schools not accredited by the American Veterinary Medical Association who are in the United States but not able to practice while stuck in an overburdened process for obtaining the needed credentials for licensure. The second are veterinarians trained and practicing outside the U.S. who want to come to and work in the country on an employer-sponsored visa known as H-1B.

"We were hoping to have lots of the former see New Hampshire in a new light and be interested/willing to move here," Dr. Claire Lindo said in an email to the VIN News Service. "That hasn't happened."

So Lindo, who owns a small animal practice in the southern part of the state, focused on the second group. She is in the process of sponsoring three veterinarians — from Ecuador, Nigeria and Pakistan — to work under her supervision while they complete the process of becoming fully licensed.

Creating provisional licenses for foreign-trained veterinarians to address perceived workforce shortages has become something of a trend in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, with eight jurisdictions across the United States and Canada adopting them since 2021.

Graduates of schools not accredited by the AVMA Council on Education need an education equivalency certificate in nearly all states and provinces to qualify for a full license. They can do so by completing a four-step program administered by the AVMA or a three-step program administered by the American Association of Veterinary State Boards (AAVSB).

Both programs can take years to complete — a period that's been lengthened by a post-pandemic surge in applications for certificates, causing particularly long waits to obtain a slot for a key exam in the AVMA program.

In all, 16 jurisdictions — nine of 50 states and at least seven of 10 provinces —allow veterinarians who are well underway in earning their equivalency certificates to obtain a conditional license. While their specifics vary, all require the temporary license-holder to work under the supervision of a fully licensed veterinarian.

Two avenues to full licensure

The older, more established path to full licensure for graduates of non-AVMA-accredited programs is known as the Educational Commission for Foreign Veterinary Graduates (ECFVG). It was created by the AVMA in 1973 and is recognized across the U.S. and Canada.

The program has four steps: credential verification, an English proficiency exam, a test called the Basic and Clinical Veterinary Sciences exam, and the culminating Clinical Proficiency Examination (CPE), a seven-part test that includes performing surgery. The CPE is where the backlog is occurring, in part because most test-takers fail at least one part of it and must get back in line to retake the failed portion.

At one time, the ECFVG allowed participants to do an evaluated year of postgraduate clinical experience in lieu of the CPE, but that option was discontinued in 2007.

According to the AVMA, more than 2,000 candidates are enrolled in the ECFVG program, although not all are actively progressing. Seats for the CPE are available for booking at the beginning of each year. This year, 230 seats were available for the full exam, and 280 were reserved for retakes. Historically, testing dates are released twice a year, so candidates who are unsuccessful in securing a seat will have to wait for the next window to try again.

In 2002, the AAVSB established the Program for the Assessment of Veterinary Education Equivalence (PAVE) as an alternative to the ECFVG. Today, 47 states in the U.S. and all provinces in Canada accept PAVE. Over the past six years, approximately 100 candidates have applied to the program each year.

Under PAVE, applicants must submit a verification of their credentials and English proficiency before taking a test called the Qualifying Science Examination. The next and final step entails completing an "evaluated clinical experience," or ECE. For this step, PAVE applicants enroll in an AVMA-accredited veterinary school to complete the same clinical rotations as regularly enrolled students and achieve passing grades.

PAVE warns on its website that there may be a wait for the ECE. James Penrod, AAVSB chief executive, said that waiting periods depend on qualifications determined by each participating veterinary program.

"Some have more stringent requirements than others, and the volume of candidates to one particular program may be a determining factor for acceptance," Penrod explained in an email. "PAVE candidate applications to the ECE are evaluated by the same criteria for veterinary students, and the school determines acceptance, not the AAVSB. The number of seats available may fluctuate based on the number of veterinary students already enrolled and continuing their program."

States with temporary permits

VIN News reached out to regulators in every U.S. state and Canadian province to ask whether they have provisional licenses or permits for foreign-trained veterinarians. Of the nine states that offer relevant licenses or permits, some, but not all, provided information on the history of their respective program and how many participants it's had or has. Here's a synopsis:

Delaware authorized temporary licenses in 2006, the state's legislation shows.

Update coming on

Clinical Proficiency Exam

The Clinical Proficiency Examination has been in the spotlight in recent years because candidates have been unable to secure one of the limited number of seats for the test due to a backlog. However, an AVMA solicitation for veterinarian volunteer test reviewers does not indicate that how the test is administered might change.

Georgia established limited licensure in 2012. This month, the state began offering a new limited license for graduates of foreign veterinary schools who are board-certified. With this license, veterinarians are permitted only to practice within their certified specialty area.

Kentucky in 2023 extended an existing special permit to ECFVG and PAVE participants. Earlier, that special permit was available only to accredited school grads who hadn't yet passed the North American Veterinary Licensing Examination (NAVLE).

Massachusetts has had a provisional permit since at least 2017. The state has issued 12 permits. There are no current provisional permit holders.

Michigan appears to have the longest-running limited license dating to at least 1982. Eight veterinarians hold the permit.

Minnesota created a temporary license in 2008.

Nevada began a "veterinary graduates awaiting licensure" program in 2021. It may be the most subscribed program in the country, with 51 license holders.

New Hampshire law creating its conditional license took effect as of September 2024, and the first license was granted in April. So far, four have been given — including one to an H-1B visa holder sponsored by Lindo.

Utah began offering a special temporary license in May 2024. So far, seven veterinarians have received the permit, six of whom have been approved for a one-year extension.

New York is an outlier. While it doesn't offer a provisional license, it also doesn't require equivalency certificates for full licensure. For those without a certificate, the state offers a case-by-case evaluation of foreign graduates to determine whether a candidate has received the necessary training to be licensed.

States with provisional licenses or permits generally offer them for one to two years, with an option to renew. Georgia's limited licenses are good for three years. In some programs, candidates must have first passed the NAVLE to qualify.

More recent and widespread in Canada

At least seven of Canada's 10 provinces offer conditional licensing for veterinarians in equivalency programs. More than half instituted their respective programs recently. British Columbia adopted a provisional license in 2021, followed by Quebec in 2023, and Alberta and New Brunswick in 2024. Ontario was first in 2011. Manitoba followed in 2017. VIN News was unable to determine when Saskatchewan began making temporary licenses available.

Conditions for temporary permits in Canada are similar to those in the U.S.

A potentially nationwide program, called the "limited licensure project," is under development in Canada, according to Jan Robinson, the registrar and chief executive officer for the College of Veterinarians of Ontario, a regulatory body.

Robinson told the VIN News through a spokesperson that the organization has been working with veterinary regulators across Canada to develop new competency assessment tools that would allow experienced, internationally educated veterinarians to seek a limited license in equine, production animal or companion animal practice.

"This new licensure pathway, once implemented, will assist in qualifying more veterinarians more quickly," Robinson said in an emailed statement. "These individuals would receive general licenses with limitations enabling them to practice in those areas where they have demonstrated competencies."

In 2024, Ontario and Alberta tried out the competency assessment tools, Robinson said. Results of the pilot projects have since been presented to each provincial veterinary regulator, and they were asked to consider formally adopting the limited licensure program.

Edie Lau and Lena Beck contributed to this report.

July 11 update: Yesterday, the Council of the College of Veterinarians of Ontario (CVO) announced it had approved a new "pathway to licensure" that will allow experienced, internationally educated veterinarians to seek a limited license in equine, production animal or companion animal practice. Ontario regulators will use a newly created North American Essential Competency Profile to evaluate candidates for the special license. The competency profile is based on assessment tools piloted in Alberta and Ontario last year.