Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

Option 1 omits Oct 2024 poll, giving more consistent intervals and trend line

Business has been unusually bumpy at Dr. Andy Anderson's single-doctor practice in the affluent city of Westlake Village, California. Some days this year, the veterinarian has had just two or three appointments, the phones silent all day. In recent weeks, demand has picked up to the point that Anderson's schedule is almost full again. Still, visitors are being more careful with their money.

"A large number of my clients come from very high socioeconomic backgrounds, and I am still hearing a lot more concerns regarding finances than I have in the past," said Anderson, who has been at the practice for three years. "A lot of clients who have always done recommended diagnostics are now declining them, and we are getting many more cost-shopping phone calls than before."

Anderson's experiences are echoed by more than a dozen veterinarians who posted recently to a discussion board of the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of the VIN News Service, to lament that demand is heading south.

Visits to veterinarians had already begun moderating around three years ago as a pandemic pet boom faded and runaway inflation weighed on household income. Now, even as inflation appears to have come off the boil, the outlook is getting gloomier, as the administration of the United States President Donald Trump tests consumer confidence with trade tariffs that threaten to drive prices higher. Deep job cuts in the public sector are contributing to a mood of insecurity.

"I have several clients who work in the government, and many of them have either already lost their job or are worried they are about to lose their jobs," a veterinarian in Virginia posted in April.

Business isn't slower for everyone, but financial pressure is rising all the same. As Dr. Bruce Henderson in Clifton, New Jersey, posted recently: "We remain very busy with open appointments a rarity unless there is a last-minute cancellation. Despite this, and the fact that the hospital is grossing more per month than ever, everything (especially staffing) is more expensive than ever, and just as much goes out as comes in."

Pooled practice data shows downward trend

On average, veterinary visits are falling, according to information collected from thousands of clinics by three unrelated entities — data provider Animalytix, pet drugs and supplies distributor Vetsource and diagnostic laboratory company Idexx. Practice revenue, meanwhile, appears to be flattening out. For the 12 months to May 24, for instance, revenue rose 0.5% year-on-year, down from a rise of 4.2% recorded the same time last year, according to figures collected from more than 3,000 practices in the U.S. by Animalytix.

An indication that prices might be rising too high for consumers to absorb came in March, when BluePearl, a chain of emergency and specialty clinics owned by Mars Inc., the world's biggest owner of veterinary practices, announced it was lowering prices by 20% to 30% on a number of procedures.

In an email sent to primary care practices across the U.S., BluePearl wrote: "As your partner in veterinary medicine, we are sensitive to the economic stress many pet owners face. By making these procedures more affordable, we aim to increase access to specialized veterinary care as an extension of your practice."

The procedures listed by BluePearl pertain to surgery involving the intestines (enterotomies), stomach (gastrotomies), uterus (pyometras) and spleen (splenectomies). Surgery to clear feline urethral obstruction also is on the list.

Nationwide, veterinary prices are still rising faster than overall inflation, which in April was 2.3%. During the same month, the consumer price index for veterinary services was up 4.6% year-on-year, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

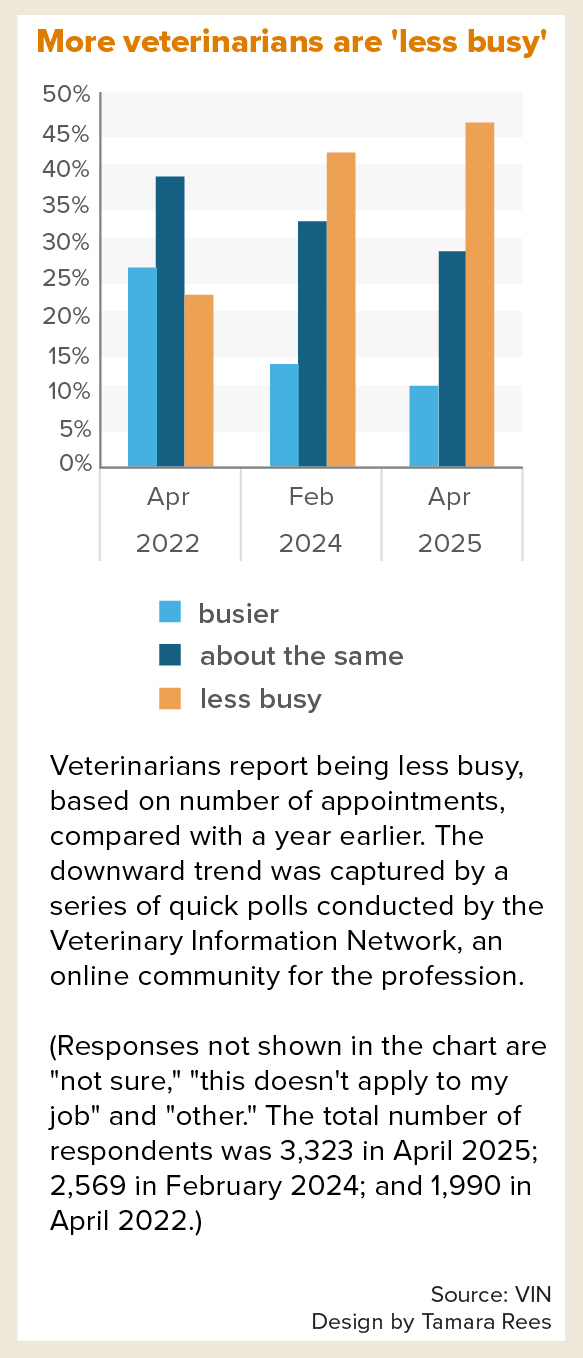

A series of surveys of veterinarians show a trend in moderating demand. In a one-question poll on VIN in late April that drew 3,323 respondents, 46% reported being "less busy" than they were a year ago. Only 11% were "busier" and 29% were "about the same." (The remaining responses were split among "not sure," "this doesn't apply to my job situation" and "other.") VIN quick polls asking the same question in February 2024 and April 2022 capture the progression: In April 2022, 23% of respondents said they were "less busy" — half the proportion of those this April.

Similarly, a sentiment gauge compiled by Veterinary Management Groups (VMG), a consultancy for independent clinics owned by practice management firm Covetrus, indicates veterinarians are markedly downbeat. Its economic barometer, an index created from a monthly survey of its around 800 members, came in at 73.7 for May, putting it well into negative territory. Any reading below 95 indicates that "veterinary economic conditions are worsening and do not have a positive outlook in the next year."

VMG's chief economist, Matt Salois, recently said the outlook has become "very gloomy," noting April's barometer reading of 65.0 was the lowest since the gauge was created in September 2023. "In March, we did a deeper dive on what our members are concerned about in terms of the economy, and the top responses were related to inflation, reduced visits, tariffs and trade policy, and political instability and volatility," he said.

'On again, off again tariffs' hit demand

Clinton Neill, an economist at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, said pressure on practices is twofold: "On one hand, pet owners are stretched pretty thin. People are putting off visits," he said. "And on the other side of that, inflation for veterinary services is still well above inflation for the rest of the economy."

Neill said uncertainty alone about what tariffs will stick could be causing households to spend less. Trump has frequently chopped and changed the details of his tariff plans. Last week, a U.S. trade court blocked tariffs he'd put into effect, arguing an emergency-powers law he used to justify the changes didn't apply. A day later, an appeals court temporarily reinstated them, pending an appeal hearing.

Because many goods used by veterinarians in the U.S., such as equipment and pharmaceuticals, are manufactured overseas, higher tariffs could push up veterinary prices even in the face of falling demand, Neill said.

Overall, Neill doesn't see demand for veterinary care in a tailspin. "We haven't crashed and burned," he said. "We had a big increase in demand partly brought about by Covid," he said, referring to the coronavirus pandemic, "but the market corrects itself."

Others see a more ominous future.

"I think an economic earthquake is on the horizon," said Jon Dittrich, a VIN practice management adviser. Based in Knoxville, Tennessee, Dittrich ran his own consultancy for decades.

He maintains that the U.S. economy is being severely disrupted by the Trump administration's "on again, off again" tariff threats and public spending cuts. "People are understandably nervous, and when people are nervous, they cut down on discretionary spending, which is where veterinary goods and services fall," he said.

Should the economy tip into recession, the impact on veterinary practices may not be immediately apparent. That's because, Neill said, there tends to be a time lag between the economy wilting and a drop off in veterinary visits. "People go to a veterinarian for a wellness check typically once a year," he said, compared with their much more frequent purchases of food, gasoline and the like.

A long-term societal shift toward viewing pets as family members could support continued demand for veterinary care regardless of how the economy is faring, as might advances in care that enable pets to live longer. Nevertheless, the veterinary profession is not recession-proof, Dittrich and Neill agree.

Dr. Karen Felsted, a veterinarian who runs a management consultancy in Dallas, once thought the profession was, more or less, impervious to recession. She changed her mind following the Great Recession of 2007 to 2009, which clearly hurt demand for veterinary care.

No recession is necessarily the same as another — the brief one during the pandemic boosted demand for care. Now, Felsted worries a more severe downturn could be afoot. "This one, if it comes, concerns me because I think some things are different," she said. "The price increases have been so high and consumer confidence is down dramatically here in the U.S."

Corporate consolidators go easier on acquisitions

Besides tariffs, Dittrich said another factor that could fuel continued high prices for veterinary services is the market power of large corporate consolidators, many of which paid extraordinary sums for veterinary practices during the high-demand period of the pandemic. "The consolidators are finding out they are not making money from all their very generous practice purchases," he said.

Corporate consolidators own about 30% of general practices and about 75% to 80% of specialty practices in the U.S., together accounting for at least 50% of industrywide revenue, according to an estimate last year by Brakke Consulting, an animal health group based in North Carolina.

The rate at which big companies acquired practices slowed substantially in 2023 as interest rates rose — making it more expensive to borrow money for purchases — and veterinary visits declined. Sales apparently remain relatively subdued today, and prices, too.

The number of purchases made by private equity firms of veterinary businesses in the U.S. rose to 91 in 2024, up from 63 in 2023 but still down from 182 and 231 in 2022 and 2021, respectively, according to consulting firm KPMG.

Felsted said she sees independent practices sold to consolidators fetching sums equaling eight to 12 times their annual earnings, down from multiples in the high teens and low 20s paid in 2021.

"There can be some outliers," she said. "But if it's going to be more, like, over 12, those are going to have to be exceptional practices."

The decrease in valuations, she said, presents an opportunity for smaller buyers to explore practice ownership.

"If you're an individual veterinarian and you want to own a practice, either you could do a startup or you could buy one that might not be the greatest practice ever but at least doesn't have a fatal flaw," she said. "You could do a lot with that, particularly if you focus on what I would call affordable pet care."

Signs that some large hospital chains are under pressure have arisen at Thrive Pet Healthcare, which owns more than 360 veterinary practices in the U.S. In March, Thrive restructured its debt in what the ratings agency Standard & Poor's described as a "de facto default." The company was able to extend its debt due date to June 2028.

A smaller company, My Pets Wellness, which an archived version of its website shows owned 10 practices in the U.S., abruptly went out of business in April, citing "an unexpected and overwhelming financial situation that left us with no other option but to shut down operations right away." On a larger scale, pet medication distributor PetIQ shuttered 282 practices over 2023 and 2024 that were located inside the stores of partners such as Walmart and Meijer. In its case, PetIQ blamed rising costs caused by a tight labor market for veterinary professionals.

Could demand for veterinarians fall, too?

Even before the onset of the pandemic in 2020 and especially since then, demand for veterinarians has been high. That's changing, but not dramatically, Neill and Felsted said.

"We have seen a loosening in the labor market," Neill said. "It's still tight, there's still a need for veterinarians, but it's not as bad as it was. And part of that, I think, is just because demand for veterinary care has gone down."

Felsted said, "I still have practices that I work with that are finding it a nightmare to hire. Sometimes I worry, 'Is the problem with your practice or the labor market?' I think it's a little easier now, but you're still going to have to pay what it takes to get people."

Down the line, the workforce demand dynamic could change substantially, with two new veterinary schools opening this fall, eight projected to open in 2026 and one in 2027, potentially bringing the total number of U.S. schools to 45.

Dittrich anticipates that the completion of new veterinary schools, coupled with falling demand, will turn a labor shortage into a labor glut, putting downward pressure on veterinarians' salaries. "Associates are in for a rude awakening," he said. "I think it will happen in the next five years."

In Westlake Village, Anderson has a more immediate concern: that a slew of empty slots don't start reappearing in his schedule.

"Overall," he said, "it seems that there is a lot of uncertainty regarding just about everything right now."