Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

Our test subjects

Photos by VIN News Service

Clockwise from top left: Murphy, Wallace, Pearl, Jeeves, Luna and Laddie. At center: Jet the cat.

Suppose someone said they could tell the age of your dog from its slobber. Would you believe it or dismiss it as hocus-pocus?

Several vendors of at-home genetic test kits make exactly that promise. Curious whether it's true, and if so, how the technique works, the VIN News Service put one of the tests to the test.

Our anecdotal results suggest that while the test isn't perfect — and no one claims it is — it's no sham. Details on the animals tested and the outcome follow. But first, some background on the science.

It's not the slobber that's the magic but DNA in a swab of saliva that yields information. Estimates of age are derived through tools from the field of epigenetics, which is concerned with gene expression. Genes can be silent or expressed. The environment and behavior of an organism — whether a dog, a person or any living being — can cause its genes to turn off or on.

Scientists detect evidence of gene expression and repression through the absence or presence of chemical compounds known as methyl groups. When a segment of DNA is "methylated," its expression is changed — usually muted. Over time, patterns of gene methylation change.

The understanding that age affects DNA methylation dates back decades. The development of epigenetic clocks is more recent, born out of pioneering work published in 2011 by a team at the University of California, Los Angeles. Using saliva samples from people, the researchers identified specific methylation markers that significantly correlated with age.

Matt Kaeberlein, a biogerontologist and co-director of a research endeavor called the Dog Aging Project, compares DNA methylation to dings and dents on an aging car.

"You can think of methylation marks as accumulated damage over time," he offered. "Not unlike a car, there are certain parts of the genome that are more likely to get damaged — maybe the windshield or the front fender, where most of the rocks are going to fly up and hit.

"And so," he explained, "scientists, by looking at the changes in these damage patterns over time in lots and lots of different people, have been able to identify the sites that are most often damaged. And it turns out, across the population, there's some predictability about how fast that damage is going to happen."

By looking at hundreds or thousands of such sites, researchers can identify the locations that are most predictive, he said, yielding "fairly high precision for saying this dog or this person or this mouse — you can actually do this in any animal, apparently — has been alive this long. And that's all the test really is."

In short, the study of genetics has delivered a means of estimating someone's age via biochemical markers on their DNA.

Whether a given test uses the technique well, however, is a separate question.

"The devil's in the details," Elaine Ostrander, a geneticist and head of the Dog Genome Project at the National Institutes of Health, told VIN News during an interview in December. Ostrander coauthored a study published in 2022 on DNA methylation clocks for dogs and humans.

As an example of one potentially complicating factor to account for, Ostrander, who studies the genetics of cancer, pointed out that malignant tumors might affect methylation. In dog breeds that are highly predisposed to cancer, this could pose a significant issue.

Murphy_Luna

"If you're a Bernese mountain dog, your chances of getting histiocytic sarcoma are 25%," she said. "If I were designing [an age test], I would want to look at Bernese who are 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, who did and didn't have this cancer, and see if there are methylation changes, and if so, in what tissues?"

Any methylation changes wouldn't necessarily occur uniformly across cell types, she said. "Maybe there's going to be differences in methylation patterns between affected and unaffected dogs in blood but not in saliva," she mused. "I don't know."

The overall question for breeds with strong susceptibility to certain diseases is, are methylation patterns affected "in a way that obscures your ability to say how old your dog is?" she asked.

Dog owners want age information

A search of the internet turns up at least four commercially available tests that are marketed as able to determine a dog's age based on its epigenetic profile. VIN News opted to test a kit sold by the company Embark, which provides relatively detailed information, including citations, about the science behind the test.

Embark was founded by a pair of brothers, Adam and Ryan Boyko. Adam, a biologist, is an associate professor at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. Ryan has a master's in public health.

Adam Boyko joined the Cornell faculty in 2011 as a canine genomics researcher. His goal, he said was getting "big dog datasets for big discoveries."

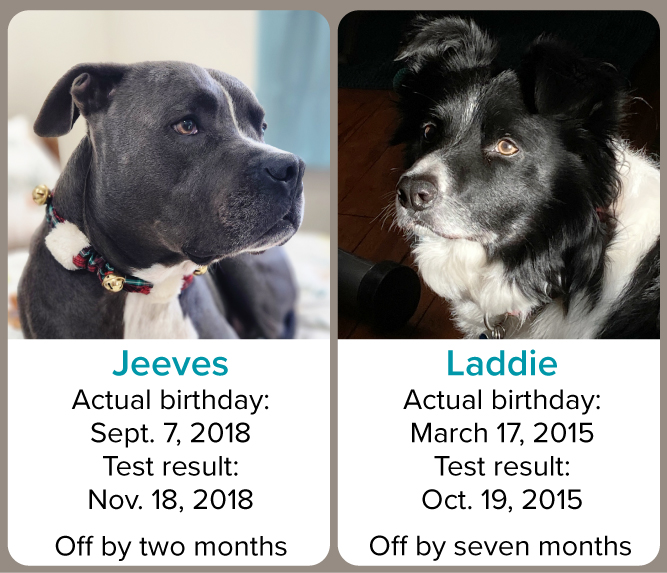

Jeeves_Laddie

With his brother, who was studying disease transmission, Boyko collected DNA from dogs of a variety of breeds, from sick dogs and healthy dogs. They traveled the world to collect samples from street dogs, an underappreciated demographic. "People were trying to use data from purebred dogs and wolves to study origins of dogs — that's like studying the origins of humans by studying European royal families," Boyko said.

Friends and family volunteered their dogs' DNA and asked if the scientists could decipher their breeds. The first consumer kit to determine dog breeds had debuted in 2007; the concept was out there, but the market was young.

Boyko developed a breed test while at Cornell, which later licensed the intellectual property to the business that became Embark. Since mid-2016, the company has run the breed test on upwards of 2.5 million dogs, according to Boyko.

Some customers, apparently confused, complained, "I thought your test would tell me how old my dog is."

But the same genetic test cannot produce both age and breed information. While both types of analyses involve the use of chips and algorithms to find genetic markers, what they look for in the DNA is distinctly different. Breed tests are based on dogs' DNA sequences, which do not change over time. "But there are other aspects of your DNA — epigenetics — that can change," Boyko said. "That got us thinking."

That thinking led to Embark's Dog Age Test.

How accurate is it?

To test the test, we recruited six dogs whose dates of birth are known exactly or within a couple of weeks of their birth. They are:

Wallace_Pearl

- Luna, a Newfoundland, almost age 1 when tested

- Pearl, a Sheltie, nearly 4 when tested

- Jeeves, an American bully, close to 6 when tested

- Laddie, a border collie, 9½ when tested

- Wallace, a corgi, nearly 11 when tested

- Murphy, a Labradoodle, 11 when tested

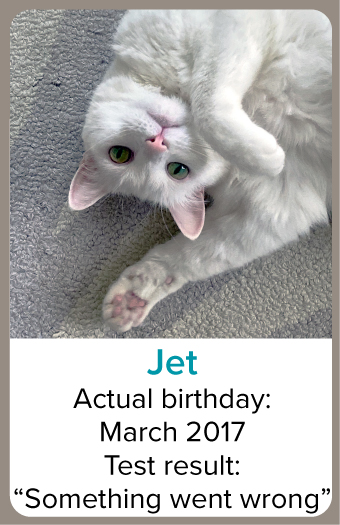

For a twist, we also submitted the saliva of a cat, Jet, who was 7½ at the time of her test.

On its website, Embark describes the test's accuracy this way: "77% of dogs have a true birthday within 12 months of their estimated birthday."

Results on five of the six dogs in our group came within a year of their actual birthday, for an accuracy rate of 83%. In our modest, unscientifically controlled project, Embark hit its mark.

Wallace's results just squeaked into the "accurate" column — his estimated birthdate was off by one day short of a year. Any more, and the accuracy rate of our submissions would have fallen to 67%.

Pearl's result was unquestionably off. Embark said she was two years older than she really is.

As for Jet the cat, Embark wasn't tricked into producing results. "Something went wrong with your Age Test swab," the company said in a message to her owner. It didn't specify what went wrong, exactly. "Unfortunately, test swabs sometimes go missing on their way to our lab, arrive damaged, or don't contain enough saliva to process," it said, offering a fresh kit for a redo. "We apologize for the inconvenience."

Reaching its accuracy target has been a work in progress for Embark. Shortly after it introduced the test in October 2022, the company temporarily withdrew it from the market and issued refunds.

Jet

"We had an initial algorithm that showed most dogs accurate within a year," Boyko recalled. "We felt good, green-lit that and, of course, we're continually acting to improve that." Internal research indicated that early results fell outside the promised range.

"Most of the results were accurate within 18 months, but that wasn't what we were advertising to customers," Boyko said. "We needed more samples to train the algorithm."

After making refinements for the better part of a year, the company re-introduced the kit in late 2023.

Let's look again at the promised accuracy and parse its meaning: "77% of dogs have a true birthday within 12 months of their estimated birthday."

Seventy-seven percent means that 23%, or nearly one out of four, will have a result that is not within a year of their actual birthday.

"A true birthday within 12 months of their estimated birthday." That means, as Boyko himself said when the target was described to him by Embark staff, "Literally, you're telling me any day of the year could be my dog's birthday."

In their test results, kit users are given a single birthdate. It represents the midpoint in the 12-month span of possible dates.

Trying to convey the scientific uncertainty, Embark for a time did not give a specific birthdate, Boyko said, but that did not go over well. "For a significant and vocal proportion of customers, they are looking for a way to have a birthday for their dog that they don't feel like they're just inventing, picking a day at random off the calendar," he said.

Adam Boyko and his 13 yo dog, Penny

Photo by Kelly Boyko

Embark co-founder Adam Boyko, a Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine biologist, has repeated the age test over the years on his dog, Penny, who is nearly 13. Boyko said the test has been consistently accurate on her, give or take six months.

In other words, customers want a date from a scientific authority. Embark now provides not only an exact date but identifies the dog's birthstone, too.

Refinements and further interpretations in the works

Going back to the nearly one out of four dogs whose age test results fall into the error zone, Boyko speculated that in at least some instances, the dog is aging more quickly or slowly than normal. Put another way, the dog's biological age might differ from its chronological age.

Emphasis on the "might." According to Aitor Serres-Armero, a postdoctoral fellow in Ostrander's comparative genetics laboratory, the most effective chronological age DNA methylation markers generally are believed to be uninfluenced by environmental exposures, disease and other such factors that affect biological age. "That's what makes them such good chronological age predictors," he said.

However, because epigenetic clocks use many markers — sometimes hundreds — a clock could be designed that enables it to detect biological age deviations, Serres-Armero said. He noted that the study of biological age is still evolving.

Asked whether Embark's age clock combines chronological and biological markers, Boyko said: "We've deliberately calibrated the age test for chronological age including dogs of diverse breeds and backgrounds to try to average over some of the biological effects. Nevertheless, some signal of biological age probably persists in some dogs, making the calendar age test over- or under-estimate their age."

He added, "This is, of course, really interesting from a scientific standpoint, and we hope by growing our database of dogs and identifying these outliers, we can learn more about healthy aging."

As for Ostrander's hypothesis that genetic predisposition to disease might confound the age results in some breeds, Boyko said the ability to determine whether that's the case, and if so, accounting for it, will require much more data. "It's ... not just the number of samples needed but the amount of information for each sample," he said, noting that it's helpful when owners take the time to fill out health surveys on the website for their dogs.

"Right now, we're working on growing the database for the epigenetic data," Boyko said, "and we're focused on continually seeing, are there improvements to the model that we can make for age?"