But five veterinary schools fell below accreditation standard on national licensing exam

Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

NAVLE_pass_7year

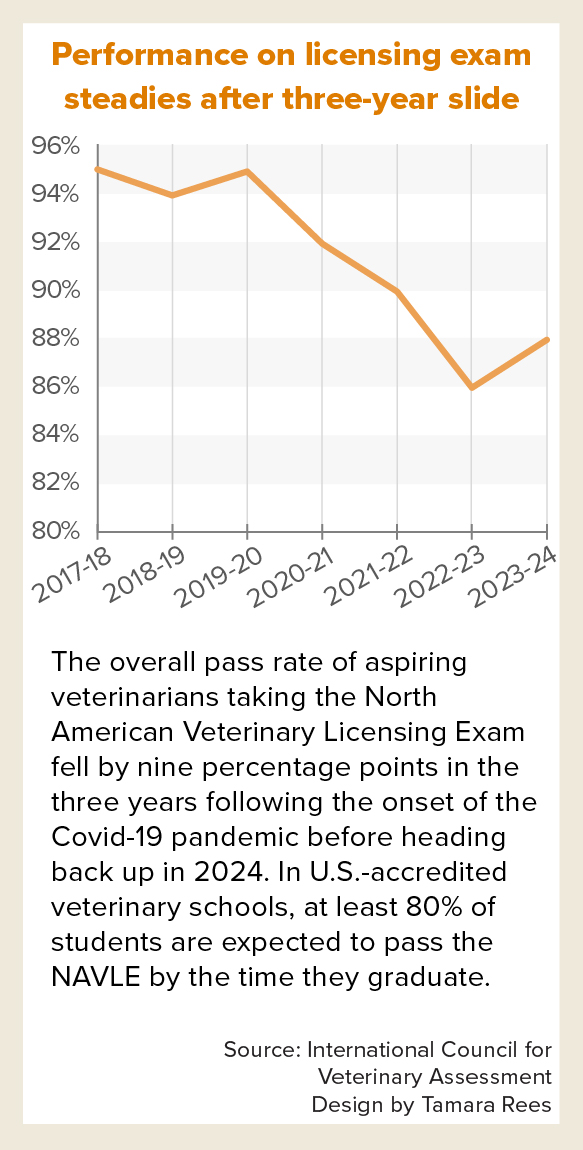

After three straight years of decline, the percentage of students who passed the North American Veterinary Licensing Examination ticked up in 2024 to 88%, albeit still significantly below the 2020 pass rate of 95%.

The incremental improvement could be a sign that upheaval from the Covid-19 pandemic, which began in 2020, is abating. Remote instruction and related factors have been cited as significant — though not exclusive — contributors to the performance slump. The national licensing exam pass rate bottomed out at 86% in 2023.

Amid the upturn, however, is a troubling trend: Five programs posted pass rates below 80%, a minimum criterion from the accreditor of veterinary education in the United States and Canada, the American Veterinary Medical Association Council on Education. The expected pass rate is part of the outcomes assessment, one of 11 accreditation standards set by the COE.

The schools are Michigan State University; St. George's University in the Caribbean country of Grenada; Tuskegee University in Alabama; the University of Arizona; and Western University of Health Sciences in California. They are five of 39 accredited schools with students eligible for the exam in Canada, the Caribbean and the U.S.

Deans at three of the programs told VIN News they view the declines as a serious concern. In their experience, they said, the pandemic still exerted a drag on the performance of the class of 2024, and they described extensive actions to better prepare students at their institutions for the test.

How pass rates are calculated and affect accreditation

Aspiring veterinarians must pass the 360-question NAVLE before they can be licensed to practice in Canada or the U.S. — and most students of veterinary schools in the two countries take the exam. The only other accredited programs with a majority of students taking the exam are St. George's and Ross University on St. Kitts. Many of their students are from Canada and the U.S. and plan to return home to practice.

Pass rates reported by the International Council for Veterinary Assessment (ICVA), which creates and administers the exam, are referred to as "ultimate performance" rates that reflect the top scores derived during either of two testing windows — one in late fall and the second in the following spring. Students may take the test twice during a 10-month period before graduation. If they fail the first try but pass on the second attempt, the second score is the one factored into their school's performance. (Starting with the 2025-26 testing cycle, ICVA will offer the exam in three windows.)

Dr. Heather Case, chief executive of the ICVA, told VIN News in an email that roughly 14% of students who took the NAVLE for the first time in November-December 2023 retook the test in April 2024. The test is pass/fail. Presumably, those students did not pass on the first try.

In its accreditation standards, the AVMA COE says it "expects that 80% or more of each college's graduating senior students sitting for the NAVLE will have passed at the time of graduation."

While a school may operate without accreditation, approval by an accreditor authorized by the U.S. Department of Education is needed for its students to access federal financial aid, including loans. There are no unaccredited veterinary colleges in Canada or the U.S. There are numerous unaccredited programs in the Caribbean.

Colleges that fail to meet the minimum pass rate for two consecutive years could be placed on probationary accreditation. Programs that fall short for four consecutive years could lose their accreditation, according to the standards.

However, for programs with pass rates below 80%, the AVMA COE applies a probability calculation called the "exact binomial confidence interval" to determine whether the pass rate constitutes a true deficiency that should impact accreditation. Dr. Julie Funk, dean of the University of Arizona College of Veterinary Medicine, told VIN News that with the confidence interval analysis, the school's 79.4% pass rate in 2024 meets the standard. UA is a new program with provisional accreditation.

St. George's School of Veterinary Medicine is in its second consecutive year of falling below the 80% standard, after 79% of its students passed the exam in 2023. The program dean, Dr. Neil Olson, said St. George's has not been notified by AVMA COE of any accreditation deficiencies.

Tuskegee University College of Veterinary Medicine is in its fifth year of falling below the standard. In 2020, 79% of its students passed the exam. That percentage dropped steadily each year to 51% in 2024. Tuskegee is on probationary accreditation in part because of its test scores. University representatives did not comment for the article.

When asked about schools that have fallen below the criteria for more than one year, the AVMA responded that it doesn't comment on individual colleges and referred VIN News to its accreditation standards.

School accreditation and graduate employability as a practicing veterinarian are not the only areas of concern.

"Student loan repayment is an insidious complication of not passing the NAVLE," said Dr. Tony Bartels, a student loan consultant for VIN and the VIN Foundation. "Repayment begins after graduation even if you're not yet a licensed veterinarian. Ignoring or deferring student loans leads to higher repayment costs and a longer repayment time."

Western University applies mentoring

Dr. John Tegzes, dean of Western U's College of Veterinary Medicine in Pomona, California, doesn't sugarcoat the program's plunge from an 89% pass rate in 2023 to 72.1% in 2024.

"We had a sharp decline," he acknowledged in an interview. "It wasn't a subtle one. The [overall] average went up, and we went down by a lot."

Tegzes said Western U had been seeing a downward trajectory for a few years and had begun interventions, so he did not expect such a deep dip.

When he came in as interim dean 2½ years ago, he created a NAVLE Success Task Force. (Tegzes became dean in 2024.) The task force, made up of faculty, collected data over two years including from focus groups of alumni who had successfully and unsuccessfully completed the exam. The task force submitted a variety of recommendations to the faculty in early 2024.

"We began implementing the recommendations with the class that had this terrible pass rate, but that class, in particular, was our pandemic class," he said, referring to the class of 2024, which had entered veterinary school in 2020, the year the pandemic struck.

He quickly added: "I don't want to use the pandemic as an excuse, because it's not, but our curriculum really relies on small group interactions." He explained that because Los Angeles County, where the school is located, had very strict guidelines for return to in-person activity, the class of 2024 "literally had eight weeks on campus total in their first two years of the curriculum."

He suggested that programs built around large group lectures likely adapted to online education more easily.

The task force found "that the most critical determinant of whether a student passes or not is mentoring, and each student requires different mentoring," Tegzes said. Western U offers students a selection of mentors. All students are required to create a written NAVLE study plan, followed by NAVLE self-assessments (short versions of the test created by ICVA) at the end of their third year of veterinary school and again early in their fourth and final year.

The multipronged strategy includes providing more third-party exams, including an assessment of critical thinking. The test is administered in the first month of the first semester to identify students at risk of struggling with critical thinking skills and taking standardized tests. "When we can identify them, we can provide extra counseling and support for them through all four years," he said.

Task force recommendations will be fully implemented this year.

"Data suggests that we're already improving," Tegzes said, "but it's going to take a few years to recover."

Michigan State holds evening prep sessions

Dr. Kimberly Dodd became dean of Michigan State University College of Veterinary Medicine in August, shortly after learning that only 76% of the students who just graduated passed the NAVLE. In her email to students about the results, she included an admission.

"I told them I failed the first time," she recounted. Her point was that failing doesn't make someone a failure. She also offered her case as a cautionary example: "I failed because I didn't prepare."

Dodd said MSU had started increasing focus on NAVLE preparation a few years ago but immediately implemented additional measures in the fall of 2024. The school purchased the VIN NAVLE Review course, provided funding for VetPrep or Zuku Review, encouraged students to utilize VetPrep BootCamp, and purchased NAVLE self-assessments from ICVA.

Last fall, the program also added end-of-the-semester and end-of-the-year exams aimed at enhancing knowledge retention and integration. This spring, the ICVA Veterinary Educational Assessment was implemented to help identify areas that require additional focus in the preclinical curriculum. Faculty were also tapped to lead evening NAVLE review sessions.

"The students loved it," she said, adding that it was an opportunity for faculty to see questions outside their respective areas of expertise — a reminder of how hard the exam is.

MSU also hosted panels of recent graduates talking about personal experiences and best practices.

"We've recognized students learn differently — coming out of Covid [and] generationally," she said. "I think our students recognized their responsibility in preparing. But I think as a field, we need to better prepare them."

She also added that she is optimistic about the performance of this year's crop of graduates. "Based on all information we have to date (we won't get official info from NAVLE for months), but based on student self-reporting through NAVLE and feedback from students, it appears that our students did much better this fall," she said in an email.

St. George's mandating exam preparation

St. George's University of Grenada is one of two Caribbean veterinary schools accredited by the AVMA COE. During a recent interview, the dean, Dr. Neil Olson, led with what he considers an important point.

"Our primary focus is for day one competency, which we do very well," he said. "The NAVLE has virtually nothing to do with day one competency. How do you test on the NAVLE whether they are good at doing a lameness exam on a horse … [or] whether they can suture properly on a spay?"

He conceded that passing the NAVLE is essential for graduates who want to be licensed in North America and said it's a priority for St. George's to help them succeed on the test in greater numbers.

Olson said there are some aspects of St. George's student body, in contrast with U.S.-based schools, that put downward pressure on NAVLE pass rates in general.

He said 10% to 15% of students transfer to schools in the U.S. in the second and third terms. They leave St. George's for a variety of reasons, he said, including trouble adjusting to "island life" and to save money. After earning good grades at St. George's, some students are able to transfer to their in-state school at significant savings after initially being turned away.

"They don't accept them unless they are in the top quartile," Olson said about transfer schools. "That means we lost many students who are more likely to pass the NAVLE."

That St. George's pass rates have dipped below the accreditation standard is something Olson attributes to the pandemic.

"Overnight, we became a virtual institution," he said, "doing sutures on teddy bears. It's a void in their education."

To try to reverse the trend, St. George's last year brought on a full-time director of student success to spearhead efforts. The school has added a raft of programs, including underwriting VetPrep, a third-party preparatory service, and ICVA practice tests, and following up with students to be sure they are using the resources.

In addition, the program launched noontime sessions for students in their very first term to familiarize them with the NAVLE. "So, by the time they are juniors, they aren't asking questions about what it is," Olson said.

Last fall, St. George's began focusing on students in the lower quartile of fourth-year classes to increase support. These students are mandated to take NAVLE prep sessions eight weeks prior to the NAVLE window. At the same time, the program began offering a board-success seminar in the evenings that is mandatory for fourth-year students who fail their first attempt or don't take the test at the first opportunity.

Students who sat for the NAVLE last fall belong to the first class that didn't experience Covid upheaval while in veterinary school and benefited from some of the new programs, Olson said. He is taking heart from the early results, saying the percentage that passed on the first take was better than in recent years.

"We're hoping that we turned a corner," he said.

In an upcoming story, VIN News will take a closer look at the probability calculation known as the exact binomial confidence interval that AVMA COE applies to NAVLE pass rates.