Listen to this story.

Listen to this story.

Leadership

Photos courtesy of subjects

Top row from left: Dr. Tangela Williams-Hill, Dr. Mary Beth Leininger (Stephen Smith Images photo), Dr. Joan Hendricks

Second row: Dr. Jennifer Welser (Talin Propes photo), AK Mitchell (Joy Nabors photo)

Third row: Tara Barron (Katelyn Wilbanks photo), Dr. Karen McCormick

Bottom row: Dr. Janis Shinkawa (Karianne Munstedt photo), Dr. Eleanor Green (David Larned photo)

The panel of men who interviewed Mary Beth Leininger for admission to veterinary school were blunt about their doubts. Why should they admit her and deny a man a seat, they asked, when she was likely to drop out of the profession to get married and have children?

Leininger was unruffled. "I told them that I was very committed to being part of this profession," she recalled, "and I felt that I was capable of doing the work that was being asked of me."

The firm answer apparently persuaded the admissions team at Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine. Leininger was accepted, along with six other women, to the class of 1967. And she kept her word to stick with the career. For 29 years, Leininger co-ran a practice she owned with her husband, then went on to become the first female president of the American Veterinary Medical Association.

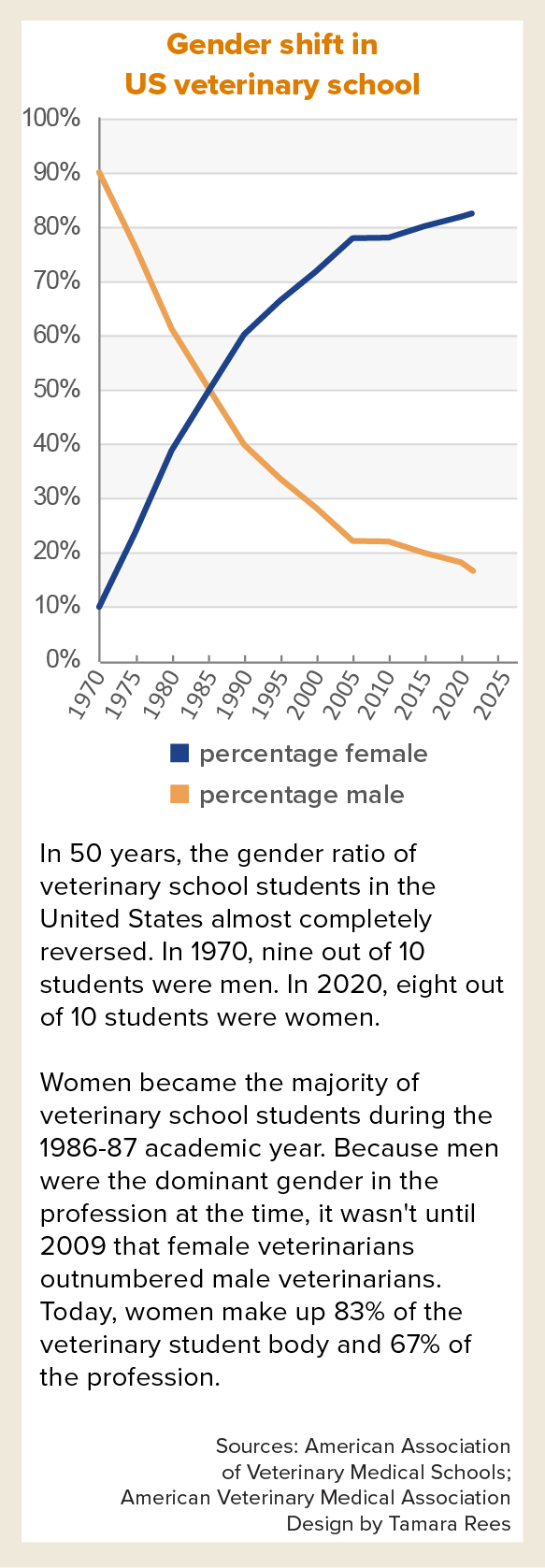

This was in 1996, during a period when the mix of men and women going into veterinary medicine in the United States was changing markedly. No longer unwelcomed by veterinary schools, female students began outnumbering male students in 1986, a trend that continues to this day.

Still, it took more than 20 years for the influx of female students to change the face of the U.S. profession as a whole — women became the majority in 2009. Today, they comprise 67% of the nation's veterinarians and 83% of veterinary school students, according to the most recent figures from the AVMA and the American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges. (Those who identify as nonbinary make up fewer than 1%.)

Being in a profession and guiding it are two different things, of course. Only recently have female veterinarians attained positions of leadership in appreciable numbers and still not necessarily in proportion to their population. The proverbial glass ceiling seemed so unyielding, in fact, that a group of advocates formed the Women's Veterinary Leadership Development Initiative (WVLDI) in 2013 to address the issue head-on. They called attention to the gender disparity, encouraged women to step up and provided assistance to enable them to do so.

A little over a decade since the initiative spotlighted the issue, here's a snapshot of where things stand:

- Women appear to have made significant progress in professional associations. For example, the ratio of women to men on the AVMA executive leadership team today is 10 to 3. Women comprise 61% of the AVMA House of Delegates; it was 29% when WVLDI formed.

- Veterinary schools' top leaders are nearly balanced among men and women, with slightly more men. At the 34 established schools in the U.S. and Puerto Rico, 15 deans are women. Among 10 programs in the pipeline, deans of five are women.

- The corporate world has been more difficult to penetrate. Almost no large animal health-related companies have a woman in the top post, much less a woman who's a veterinarian. An exception is the veterinary pharmaceutical company Zoetis, whose CEO is Kristin Peck. In addition, while the executive team is mostly men at Mars Inc., an international conglomerate that owns the most veterinary practices in the world, Mars Veterinary Health specifically is led by a woman, Nefertiti Green.

The VIN News Service spoke with more than a dozen leaders in the veterinary community to assess the progress female veterinarians have made in achieving positions of leadership. All agreed that women have come a long way. Most believe there's further to go.

In addition to identifying corporate leadership as still largely male-dominated, interviewees spoke of insidious barriers, including subtle double standards, entrenched cultural assumptions that women are followers, and self-doubt.

Measuring progress by the line to the restroom

For the pioneers who entered the profession as firsts among their sex, a supportive family was a common thread. "There was never a thought from my parents that I wouldn't be able to do this," said Leininger, who grew up in the 1940s and '50s.

Thick skin was a prerequisite. Asked whether she was treated equally once she got into veterinary school, Leininger exclaimed, "Oh, hell no!

"Certainly, the men in our classes were absolutely brutal as far as teasing us," she recalled. "All of these guys came from farms, so they were pretty rough when it came to sexual jokes and that kind of stuff. I had 12 years of Catholic education. I went to an all-girls high school. I think I spent most of veterinary school blushing."

She didn't let the crude remarks deter her and remembers female classmates being similarly resolute. "[We] were determined we were going to do this, and it didn't make a difference what anybody else said."

Institutional resistance to accepting women continued even after the landmark law Title IX, which prohibits sex discrimination by education programs that receive federal funding, passed in 1972. Dr. Joan Hendricks applied to veterinary school one year later. She distinctly recalls receiving a rejection letter from Cornell University that said, in effect, "We only admit six women; sorry," meaning that there was a quota, and it was filled.

Hendricks was, however, accepted into veterinary school by the University of Pennsylvania, a school that she later learned had a goal of admitting women in the proportions by which they applied. She was hired onto the faculty there after graduating with a VMD and PhD in 1980. Over time, she was promoted to various leadership positions, culminating with the role of dean in 2006. By then, the U.S. veterinary student body was about 78% women, although Hendricks was only the third female dean in the country.

The first was Dr. Shirley Johnston, named founding dean of Western University of Health Sciences in California in 1998. The second was Dr. Sheila Allen, in 2005, at the University of Georgia.

Hendricks said the shift was slow. "Here's our benchmark," she offered, describing a gathering of deans in Florida every winter. The indicator that women were present in significant numbers was "when it got to the point that there was a line at the women's bathroom," she said. "It was a long time before that happened."

Openly sexist attitudes still prevailed. "When I became dean," Hendricks recalled, "I had several male alumni say to me, 'You have to do something about all these women!' "

They were, as the saying goes, barking up the wrong tree. "We can't be biased against women who are competitive," Hendricks said, indignant at the memory. "We went thousands of years of men dominating. I think women dominating is just fine."

She didn't put it quite that way at the time. Especially earlier in her career, she was mindful of coming across as a good sport. "Being an angry, humorless woman is not a good look," Hendricks said. She also felt that "appearing to be ambitious was a bad idea" so did not pursue leadership jobs. It was her husband, also an academic, who raised the idea that she should be dean. This happened years before she applied. "I needed to be encouraged," she said.

Leininger, for her part, wasn't focused on breaking barriers for women when she became the AVMA's first female president. Her goal, she said, was making what she perceived as an insular organization more accessible to and communicative with its membership. Nevertheless, her election was historic for an association whose first 117 presidents were men. In the 18 years since Leininger was in the role, five more women have served in the AVMA's highest elected office, including the current president, Dr. Sandra Faeh. Its CEO is also a woman. Dr. Janet Donlin became the AVMA's first female top executive in 2016.

Another veterinarian with many "firsts" to her name is Dr. Eleanor Green. First female dean of Texas A&M University's veterinary school. First female president of the American Association of Equine Practitioners, the American Board of Veterinary Practitioners, the American Association of Veterinary Clinicians and other such roles.

Like Leininger and Hendricks, Green attended veterinary school when few women did, graduating in 1973 from Auburn University. She hadn't even met a female veterinarian before entering veterinary school. She's reluctant, though, to talk about impediments of the time, not wishing to complain. "That is just the way it was then," she said.

Her approach has been to give doubters the benefit of the doubt and live her life, running a practice with her veterinarian husband, raising three children, accepting a faculty position at Mississippi State University's veterinary school when it first opened, and rising through the ranks of academia.

Recounting a conversation with a male AVMA president whom she described as having been "very much opposed to women in veterinary medicine," Green remembered him saying, "I see how hard I work and how hard my wife works, raising the kids and keeping the house. I didn't see how anybody could do both jobs."

Green paused. "Now see, that's an honest accounting. And so, is it truly discrimination, or are there people who really don't understand how it could be done? I think it's maybe the latter," she said.

The male colleague went on to give what Green called one of the greatest compliments she's ever received. "He said, 'I see you balance your family, be a very successful veterinarian and do it all.' He told me I was an inspiration and changed his whole thoughts on women in the profession."

Chart lightly revised

Becoming the norm

In addition to showing men what they could do, female veterinarians in the 1970s and 1980s normalized women's presence for those who followed them. Veterinarians like Dr. Jennifer Welser, who entered veterinary school at Michigan State University in 1992, said that early on, "I never thought about men versus women at all." At the time, women were about 64% of the student body nationally.

Welser was exposed to the profession from birth by her dad, a veterinarian in academia and later, industry. Growing up, her idol was a colleague of her father's, a woman with a horse that she let Welser ride. She was a veterinary ophthalmologist. Welser became one, too.

Her first job out of school was at Angell Memorial Animal Hospital (now Angell Animal Medical Center) in Boston, where the medical director was a woman. Welser later worked for BluePearl, becoming the national chain's chief medical officer before it was purchased by Mars in 2015. Three years later, Welser achieved the top veterinary position at the company as the global chief medical officer of Mars Veterinary Health, which comprised about 3,000 practices in North America and Europe.

On reflection, Welser marvels that she reached the post without intention and chides herself for not directing her own path more purposefully, starting with her promotion to BluePearl medical director. "The reason they asked me was that I was the best leader! What was I not seeing in myself?" Identifying impostor syndrome as a factor, she mused, "If they had posted the role, would I have raised my hand? I don't know that I would have."

At the corporate executive level, Welser noticed a gender factor that wasn't evident earlier in her career. "I became more and more aware of some of the typical things in the classic boardroom," she said, such as that men predominated and that the few women present usually were from human resources and marketing.

But Welser said her focus was bringing a veterinarian's voice to the table more than a woman's voice. "I was so pro veterinarian," she said, because managers tended to be from outside the profession.

Still, Welser noted that her own awareness of gender equity and diversity was sharpened by Mars, which she said is attentive to the issue.

Welser stayed with Mars until 2023, when she joined the U.S. chain CityVet as its chief strategy officer in advance of becoming president of Arista Advanced Pet Care, a new CityVet-affiliated specialty and emergency practice group.

The importance of mentors and allies

Like Welser, Dr. Tangela Williams-Hill entered the profession when women were no longer a novelty. A graduate of the veterinary school at Tuskegee University in 2000, Williams-Hill is the current president of WVLDI, the women's leadership development group, and works for the pharmaceutical company Elanco in a senior training role.

Her first job as a veterinarian was at a practice in New Jersey owned by a doctor who, like her, was a woman of color. She was "a powerful, inspiring figure," Williams-Hill said of the late Dr. Carolyn Self, who became her mentor.

"She taught me not just the medical part but how to balance life and how to overcome some of the barriers to not just Black women but women in general," Williams-Hill said, telling how Self worked as a park ranger after graduating because no one would hire her as a veterinarian. Self eventually got a job at the New Jersey practice, which, at the time, was "owned by a male, of course," Williams-Hill said. "They ended up becoming really good friends." When the owner retired, he sold the practice to Self.

The story exemplifies for Williams-Hill the crucial role of supporters of all kinds. While female role models are vital, she says, there is room also for male allyship.

Dr. Doug Aspros would agree. He grew up as the eldest of three children whose mom for 10 years didn't ask for a raise at her office job for fear of losing the flexible schedule she needed as a parent. That made him sensitive from an early age to women's station in society.

Shortly before entering veterinary school in the early 1970s, Aspros had a job at a U.S. Department of Agriculture laboratory, working for a female scientist who gracefully juggled parenthood and career. Being around accomplished women in the workforce felt natural to him.

So when the women's veterinary leadership initiative came together years later, Aspros, then president of the AVMA, joined the effort. He served on the group's board for six years. He continues today to speak on the subject of empowerment, telling female audiences, "You have more agency than you think." He sometimes feels, though, that the message isn't well-received coming from a white man of his age. He ponders "how to be the right man in a female profession."

Aspros accepts his discomfort as fair. He recalled being the only man once in a room of 100 people at a conference on women in the veterinary profession. "As an avatar for men, I had to sort of fill all these roles and expectations and mis-expectations people had for me," Aspros said, feeling the pressure in his chest. "It felt like everybody was judging me."

He told himself, "This is what women go through all the time, and men don't, and they would benefit from the experience. It would help enhance their understanding."

Still 'ingrained in the culture'

The president of the Student American Veterinary Medical Association is a 31-year-old woman with a background in retail management who is just months away from graduating from the veterinary program at Lincoln Memorial University. She exudes confidence. One might hope sexism would be an antiquated concept to her. It's not.

The first thing Tara Barron told VIN News during an interview this month was: "I feel like, naturally, women aren't perceived always as the leader. I thought the Barbie movie did a really good job of displaying that as women, we feel almost inferior. I feel like it's ingrained in the culture, unfortunately."

From her own work history, Barron knows sexist behavior persists. She told of being groped by a manager, propositioned by a co-worker and hearing flat-out from a man whom she supervised, "I won't respect you because you're a woman."

Her experience with the veterinary profession has been more positive, "not misogynist at all," Barron said. "... I just feel like it's a societal thing."

Veterinary medicine lives in the context of society, of course. A fourth-year student at Mississippi State University's veterinary school, AK Mitchell, described witnessing double standards in elections for class president and vice president. Each race had a female and male candidate.

"I remember the two female candidates being criticized both for their appearances and for being loud or pushy," Mitchell said. "Leading up to class elections, neither shied away from sharing their opinions on controversial school policies or ideas for improving our class experience. Their male counterparts did the same and were seen as mature, respectable leaders."

Both male candidates won, she said, a striking outcome for a class in which men comprise only 18 of 115 students.

Mitchell is president of the national student-run Veterinary Business Management Association, a post that makes her acutely aware of expectations she believes society has for how female leaders present themselves.

"In my brain, the president of this organization has to have makeup on all the time, hair done, business dress all done up with heels. Like, if I didn't look right, I would misrepresent this organization," Mitchell said. "Now, did anyone ever tell me, 'You need to go do your hair'? No, but that was very much what I felt pressured to do."

The upcoming next president apparently feels the same. In a conversation with her, Mitchell said, "She had 20 million questions about what's appropriate to wear and what's not OK to wear. ... I hate to say it's easier for guys," she added, "but they throw on a suit, and they could wear the same suit three days in a row, and nobody would know."

Assessing where things stand, Mitchell said she believes the proportion of women in the veterinary field "has forced some change and normalized having women's voices in positions of influence."

At the same time, she worries that the profession is subjected to more disrespect than would be the case if it were more male. "When you have clients that are horrible and ugly to staff and doctors, would they be [that way to] a man?" she wonders.

Barron likes to think of her woman-dominated field as a model. "It shows the rest of the country that we are doctors and we are women," she said. "... I feel like veterinary medicine, in the grand scheme of life, is way more progressive than other industries. If we set that example, what can it do for women in other fields?"

Women connecting with women

Dr. Janis Shinkawa is chair of the board of directors of the National Association of Women Business Owners, the first veterinarian in that role. Supporting women and doing business with women is important to her.

So when she and her three female veterinarian partners set out to sell a small practice group in Southern California that they'd built from scratch in 2012, they took their time looking for the right match. It wasn't easy.

"There are not a lot of women in the private equity or consolidator space," Shinkawa said, referring to the sectors investing in veterinary practices.

Then they found Western Veterinary Partners, a rarity in that two of its top four executives are women: Carollee Brinkman and Kristin Moritz, CEO and chief operating officer, respectively.

Shinkawa said she immediately was drawn to Brinkman's style. "I found her to be running this company different from all the other companies I looked at," she said. "Their company values were very much in alignment with ours."

Brinkman, whose background is in health care finance and administration, described the difference in enterprises led by women versus men this way: "In female-led companies, there's a lot of listening that happens. ... We're not dictating and telling, but we're listening, earning trust, and you're able to make hard decisions because you've built that groundwork. We're just typically a little more patient to get where we want to go."

She said she's found that approach to be well-received by veterinarians, who, in her experience, generally are "quiet, introverted [and] cautious. So if you aren't listening, they will not share what is important to them and their team members."

Following years as the sole woman in boardrooms before becoming Western's founding CEO in 2019, Brinkman said she's delighted to work with a profession that is predominantly women. "The opportunity to partner with so many female business owners was so incredibly attractive," she said. "I don't think there are any other businesses you'd get to do that in."

A call for all

When it comes to stepping into leadership, Dr. Karen McCormick has a pitch for all fellow veterinarians: Run for office.

Just re-elected to a third term in the Colorado House of Representatives, McCormick entered politics during a pause in her veterinary career after 33 years in clinical practice, 16 as a clinic owner. Her first foray was a run for Congress when she saw the incumbent as an obstructionist rather than a problem-solver. Plus, he had no challenger. "I don't like the fact that voters don't have a choice," is how she put it.

McCormick lost, but two years later, in 2020, the seat in her state legislative district opened. Supporters encouraged her to go for it. She did and won.

During her second year in office, she discovered that the state veterinary practice act was up for renewal, which occurs about every 10 years. "How fun is this?" she thought. "I just happened to be here, and I'm the only veterinarian down here!"

More recently, "We've had some really intense discussions having to do with access to veterinary care and what are the potential solutions?" McCormick said, alluding in part to debates about establishing a midlevel veterinary practitioner role. "Yet again, I was deep in the weeds on this ... constantly educating my [legislative] colleagues: What do veterinarians learn [in school]? What do we do? What's important?"

The discussions made her aware that policymakers and lawmakers need more input from the people they're potentially affecting. "We need veterinarians in office," she said. "They're making decisions about veterinary medicine and changing laws on veterinary medicine sometimes without our voice."

As for the progress of female veterinarians as leaders, McCormick said full inclusion and acceptance have yet to be achieved.

"We'll be there when we don't have to ask, 'Is there enough diversity in veterinary medicine at all levels?' because the answer will be obvious," she said. "The danger is, it would be easy to go backwards."

She added: "I would love the day where we're just humans, all just doing our thing."