Listen to a podcast based on this article.

Listen to a podcast based on this article.

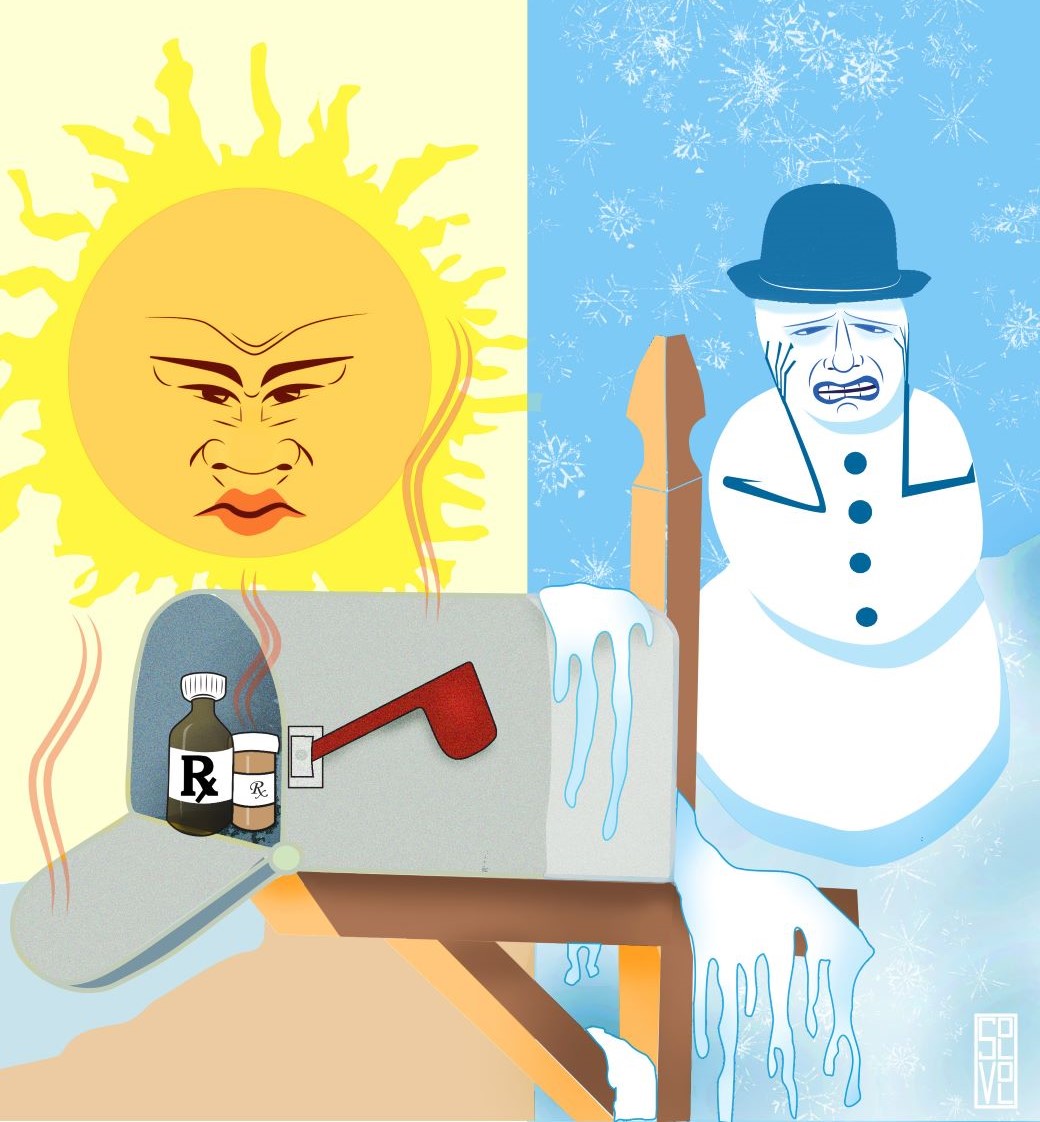

Mailorder RX

Illustration by Sol Volute

With consumers turning more to mail delivery of medications even as shifts in climate drive weather extremes, the risk of exposing drugs to harsh environments is gaining attention.

Last month, the New York Times reported that drug packages in delivery vehicles may be exposed to temperatures far outside the recommended range. (Access to the article requires a login.)

Moreover, although U.S. Food and Drug Administration requirements include appropriate storage conditions, the regulator doesn't oversee the transport and delivery of mail-ordered drugs to customers, a point made in the article and confirmed by the VIN News Service. Environmental conditions of drug mail delivery is an area under the jurisdiction of states, which may or may not address the issue.

The Times article and others published elsewhere in the past focus on the potential effects on drugs used by human patients, but the same concern applies to medications and therapeutics for veterinary patients.

VIN News consulted Dr. Dawn Boothe, a veterinary clinical pharmacologist and internal medicine specialist, to learn more about how extreme ambient conditions can affect veterinary products and what veterinarians and pet owners should know. Boothe is former director of the clinical pharmacology laboratory at Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine. Today, she works for the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of VIN News.

Here are highlights of our email exchange, edited for length and clarity.

Is there a difference in how drugs are delivered to a research lab, to pharmacies and to veterinary clinics versus to individual buyers?

At the research lab, drugs were always shipped directly to us on ice when appropriate, opened immediately and handled appropriately. When of concern, we would schedule deliveries to occur during operating days and hours. We had alarms to warn us of freezer or refrigerator failure.

Drugs sent to the veterinary teaching hospital pharmacy would be held to FDA oversight, which includes conditions of drug storage. What I don't know is whether a veterinary clinic is perceived as a pharmacy. In other words, once the drug is received by a veterinary clinic, is it held to the same federal standards as a pharmacy?

VIN News asked the FDA your question. They said that drugs subjected to extreme environments while stored at pharmacies, veterinary clinics and hospitals could be deemed adulterated or misbranded, which is against the law. So in this respect, veterinary practices are held to the same federal standards as pharmacies.

What do you make of the fact that FDA oversight doesn't extend to mail-ordered Rx deliveries?

This is disconcerting. It's an example of government regulation being unable to keep up with advances in technology — or, in this case, convenience — enabling internet purchases and interstate transport of drugs directly to consumers. In the interest of saving or making money, we are often so ready to disparage government oversight that is intended to protect consumers.

A paper published in 2023 found that drugs shipped via three different carriers spent approximately 68% of the time out of the temperature range recommended by the U.S. Pharmacopeia. (The USP sets voluntary standards for the industry, including good storage and shipping practices.)

The data presented in the paper is sobering: The problem is worse with three-day versus next-business-day shipping and, surprisingly, worse in winter. Time spent in the mailbox or on the doorstep is a problem. Climate change has caused this problem to be more urgent.

I am not sure that there is any reasonable way for oversight to be provided for exposure in mailboxes or on doorsteps. That is more of an educational issue for consumers.

The FDA recommends that makers of new veterinary drugs stress test their products for stability but doesn't require it. Have you seen drugs spoiled by unfavorable ambient conditions?

Yes, and I think that veterinarians in general are pretty quick to recognize a drug that has changed chemically. For example, they might notice a physical change in the drug, such as to its transparency, consistency or color, due to inappropriate environmental conditions — including being stored for too long.

What is more worrisome are the changes that can't be seen because the damage is molecular and not macromolecular. Those, we could not pick up even with intense visual inspection.

What can happen to drugs exposed to temperatures outside the recommended range? Besides losing potency, could they become actively toxic?

This is a really good question, one that would be easier to answer if enough people connected the dots between known exposure to extreme temperatures and an adverse reaction to the drug. A lack of this kind of data may explain why there are no good examples to offer, although it is generally understood that drugs might become toxic if excessively degraded by heat.

Besides temperature, are there other environmental factors to consider?

Exposure to sun can destroy some drugs even if the temperature is appropriate. And humidity can be devastating to some drugs, so making sure shipment occurs in an airtight package is also important.

Do you ever purchase drugs by mail for yourself or your animals?

Yes. But I am careful with what I purchase. For example, the one probiotic that I purchase comes on a cold pack with a sensor (which, frustratingly, after reading the Times article, I now understand may not work). I have occasionally purchased heartworm preventative and flea and tick products online, but I have the luxury of getting them at the veterinary clinic, which is my preference.

Would you recommend avoiding buying certain drugs or drug forms by mail?

Thinking about all drugs, not just veterinary ones, at the top of my list are proteins — for example, insulin, monoclonal antibodies and selected hormones, including thyroid hormones; and GLP-1 receptor agonists, such as Ozempic; and drugs in pressurized delivery devices, such as EpiPens and inhalants. Solutions or suspensions, especially antibiotics and especially compounded, would be close seconds.

Thermoreversible

Photo by Dr. Dawn Boothe

The effects of changing temperature on a pluronic lecithin organogel lidocaine transdermal gel were seen by researchers at the Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine Clinical Pharmacology Laboratory. In the bottom syringe, the product was properly stored at room temperature. The middle syringe shows the gel liquified after refrigeration for 24 hours. In the top syringe, when returned to room temperature following refrigeration, the ingredients separated.

Here's an interesting fact: Some transdermal gels are "thermoreversible," meaning their state changes from gel to liquid, depending on the temperature. Pluronic lecithin organogels, called PLOs, melt at cold temperatures and become solid again at room temperature. Changing temperatures can influence the distribution of the drug in the gel. So transdermal gels would be a real problem for me. I would try really hard to use a local pharmacy to compound anything other than a solid dosing form unless proper transport conditions could be confirmed.

Test strips, such as those used to monitor blood glucose, can also be harmed by excessive heat.

Are there ways to tell if drugs were not handled properly?

This is difficult unless the conditions have been so harsh that a change in the chemical structure occurs. Examples include melting of capsules, a change in the viscosity of a topical cream or gel, or clumping or clouding of liquid medication. Some drugs may give off a strange odor. For example, anything with acetylsalicylic acid would degrade to release acetic acid, smelling very vinegary. Suppositories can melt. Damaged inhalant devices may be hard to detect unless the canister has exploded. Heat can change particle size, dose delivered and other factors.

Are there considerations for safeguarding veterinary drugs from extreme weather that differ from considerations for safeguarding drugs for people?

I don't know whether FDA oversight of storage and handling applies to animal drugs once they leave the manufacturer. I am concerned that the perception that these are "just drugs for animals" may be an issue, maybe even for animal owners. They may not understand that the products they are getting in the mail for their pets are just as much at risk as a drug for themselves.

And I think this is a very real problem for unapproved drug products, including dietary supplements. I also think this may be a concern for products, possibly including vaccines, overseen by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. (Rabies vaccines, thankfully, can be given only by veterinarians, which reduces the risk of heat-related damage.) FDA rules for storage and handling do not apply to products overseen by the USDA.

The USDA also licenses some biologics. Canine parvovirus monoclonal antibody (mAb), gilvetmab, and lokivetmab (which goes by the trade name Cytopoint), are examples. Parvovirus mAb must stay frozen, whereas gilvetmab and lokivetmab cannot be frozen but should not exceed 46 degrees Fahrenheit. Their delivery, as with mAbs approved by the FDA, like Solensia and Librela, needs to be timed such that they can be handled appropriately.

I also worry about topically applied flea and tick products that are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

And the concern is heightened for products that are acquired from foreign sources.

Besides drug deliveries being left in a too-hot or too-cold mailbox or porch, are there other risks that people should be aware of, such as leaving drugs in a car on a hot summer day or cold winter night?

Yes, this is not just about mailboxes and doorsteps but any environment that gets very hot or cold. Cars — including the trunk or glove compartment or under the seat — camping, etc. And for persons living in areas prone to electrical outages, having a backup plan for sensitive drugs may be important.

What else should folks be mindful of?

It is hard to predict what temperatures are going to impact what drugs in what way. Each drug and, indeed, each formulation of that drug, needs to be studied in the conditions to which it might be exposed. That takes lots of money and lots of time. And then, how would we transmit that information to the end user?

Does that suggest we should stop buying drugs online altogether?

I do not think buying drugs online is going to stop, and it shouldn't, because the availability of online shopping helps with pricing and finding drugs that otherwise could not be accessed. But I do think it's wise to be discerning. The best way to protect your product — or if you're a veterinarian, your client's product — is through local dispensing.

For veterinarians, that means dispensing through your practice or a local pharmacy if the product is at risk for harm in a season when weather is a concern. Maybe even have the package delivered to your practice as a service to clients. For distant deliveries, the shorter the delivery time, the less the risk, so perhaps paying extra for that rapid delivery may be appropriate. Arrange the delivery date for a day when someone will be home to receive it. Increasingly, companies are providing methods for giving delivery instructions. Use a local locker service in urban areas or, if more rural, perhaps leave an insulated container on the porch to receive the package.