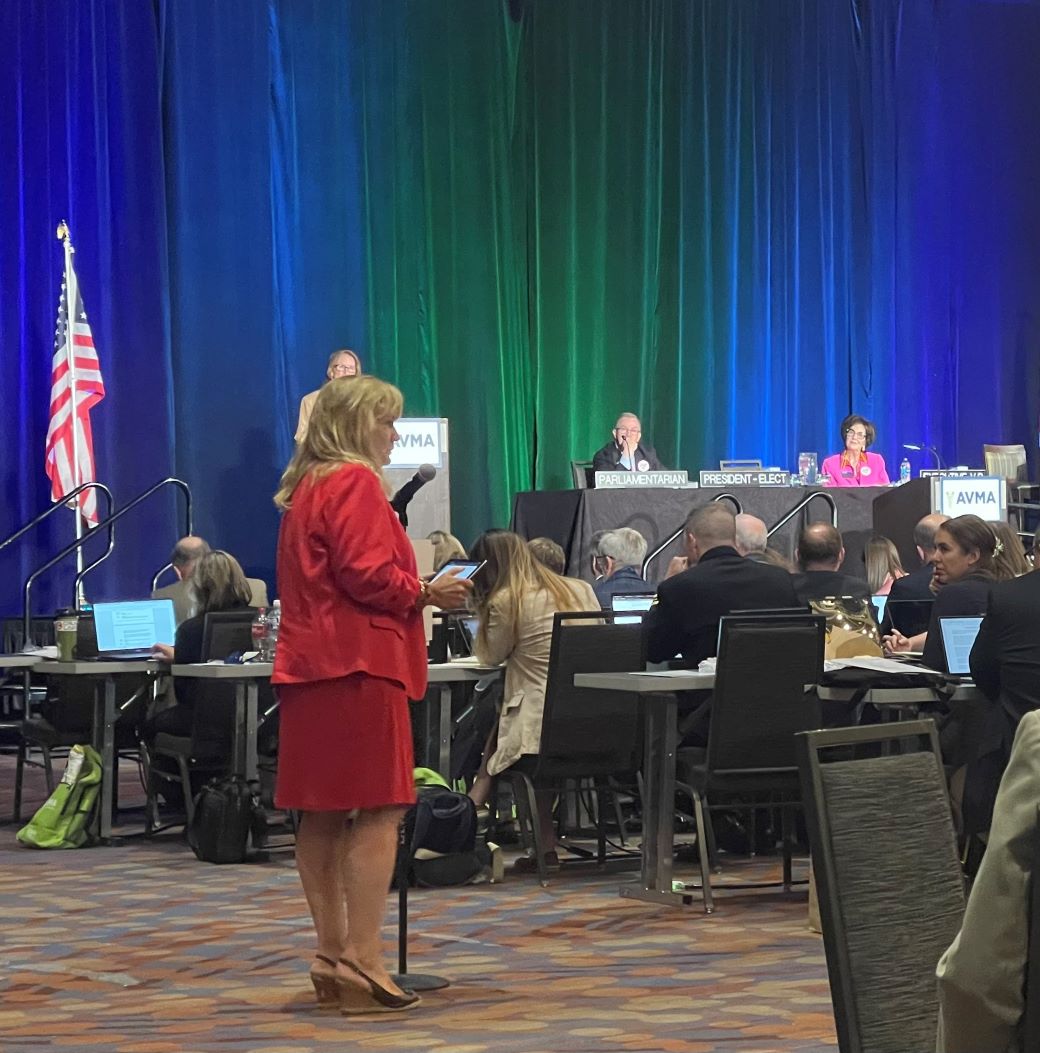

Dr. Martha Smith-Blackmore.

VIN News Service photo

Delegates asked the American Veterinary Medical Association to, among other things, develop resources on environmental sustainability for veterinary practices. Dr. Martha Smith-Blackmore (foreground) offered ways to reduce a practice's ecological footprint.

Let's come out of the ivory tower and offer a broader range of veterinary care that's more affordable and accessible for pet owners.

That was the theme of a lively discussion among 136 delegates of the American Veterinary Medical Association who gathered last week in Denver for the group's annual summer meeting, each representing a state or allied organization.

The concept of "spectrum of care" has arisen in recent years to refer to an array of treatment options that recognizes the diverse needs of clients and their pets. The continuum ranges from basic, affordable and often non-invasive, low-tech care to advanced and usually more costly and invasive care.

The House of Delegates, the AVMA's main policymaking body, asked the association to research the topic to develop policies and guidance on how to implement spectrum of care in practice, with the help of organizations such as the American Association of Veterinary State Boards and American Association of Veterinary Medical Colleges.

To illustrate the need for support, a dozen or so delegates relayed their experiences and insights into the disconnection between what's taught in veterinary school and real-world practice.

Dr. Teresa Hershey, representing Minnesota, told of a colleague whose client wanted a heartworm prevention medication. But the client declined to test his pet for heartworm first, as is advised because giving a heartworm preventive to an infected dog potentially may cause complications. The client signed a waiver documenting the decision to forgo the test, and the veterinarian prescribed the drug Interceptor.

"She thought it would be the best thing to do at that point," Hershey recounted.

Later, the client became aware of a class-action lawsuit alleging that dogs experienced severe allergic reactions to the drug. Upset, she alerted the practice's legal department. In the course of a review, the legal department chastised the practitioner for prescribing the drug without knowing the dog's heartworm status.

"They said she was negligent for giving that client heartworm preventative, even though he had signed a waiver, and that she was not living up to the standard of care at the practice," Hershey said. "I always try to offer different levels of care based on what the client can afford, but that is a pretty discouraging response."

Dr. Kaitlyn Boatright, representing Pennsylvania, emphasized the need for changes in veterinary education to better prepare students to consider a broader range of care options beyond the "gold standard" and to address the various limitations that clients and pets may face.

"It's what we need to keep moving the profession forward," she said. "… We have patients who can't physically get to a veterinarian, clients who don't have a schedule to come for rechecks, and patients who don't want to take medications. It's our job as practitioners to work with those clients and offer them a range of options within all of those limitations."

At least one veterinary college is acting on that message.

Dr. Liesa Rihl Stone, delegate for Ohio and an assistant dean at The Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine, said her institution is an "early adopter" of spectrum of care. Based on feedback from area practitioners, the program is developing a curriculum that integrates the concept, she said.

Ideals vs. reality

Many students arrive in veterinary school with an aim to practice the highest level of veterinary medicine, said Dr. Peter Hellyer, delegate for Colorado and professor at the College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at Colorado State University.

"They fear being incompetent and want to do the right thing," he said. "I don't think schools will fix that problem. We can lay the groundwork, but when they come out, they want to do the best [medicine] ever, and they might need a few years' experience to work that out."

House tackles sustainability

Offering a spectrum of care might not come naturally to students, due to the availability of technological tools, added Dr. Richard Williams, representing Florida. "Before, there wasn't a lot of great technology, you just treated your patient as best you could do. Now there's these other options where you can get an MRI or CT scan. Technology will continue to advance, and the spectrum of care will continue to get wider and wider," he predicted.

Veterinarians early in their careers are "extremely mentally stressed about not being able to just offer the gold standard," said Dr. Kristine Hoyt, representing Maine.

Prior to the House meeting, the Maine Veterinary Medical Association asked members for their thoughts on the spectrum of care concept. Hoyt noted that while newer veterinarians said they are anxious about offering lower-cost and practical care options, veterinarians in rural areas said they often are unable to practice beyond that.

"And I thought, that's a really interesting dichotomy," she said. "Most people who've practiced for many years in rural areas feel that the new grads who come to work for them just can't understand the spectrum of care and only have knowledge of the gold standard."

Dr. Gary Stuer, representing the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association, said he's talking with his new associate, a recent graduate, about the fact that care taught in veterinary school isn't always applicable in western Maine, where they practice. "It's important to have this discussion about the fact that you're learning the best way to treat patients in veterinary school, and that's wonderful. But certainly in a community like mine, often clients are either not able financially or willing to drive two or three hours to referral places for procedures," he said.

Stuer made a list of some 30 scenarios he commonly encounters in practice and plans to review them with the associate, asking, "What if our client can't afford the gold standard? What do we do?"

"I think probably one of the most important things we have as veterinarians to our clients is our ability to communicate with them and have open discussions with them," he continued. "And I think we need to be doing the same thing with our associates, especially our new grads."

Dr. Jane Barlow Roy, delegate for New Hampshire, noted that discussions about spectrum of care apply not only to clients limited by finances. In affluent communities, she said, the issue is futile care.

"There are clients asking us to do what we may feel is unrealistic with unrealistic expectations. There may be a poor outcome, but the client wants to keep going," she said.

Regulators should be on board

Another issue, Roy said, is the role of government regulators. For example, when things don't go well, a veterinarian often "gets dinged" by state licensing boards for poor documentation.

Her advice is: "Make sure you're clear and concise with your recommendations, and then follow that up with proper documentation about what [the clients] choose."

Dr. Hunter Lang, representing the American Association of Bovine Practitioners and chair of the Wisconsin Veterinary Examining Board, agreed, noting that complaints against practitioners have doubled in his state during the past three years, most of them hinging on poor communication and documentation. "Communication is critical ..." he said.

Dr. Scott Moore, delegate for West Virginia, said that for the spectrum of care concept to work, licensing boards need to be on board, given their role as regulators who may expect veterinarians to adhere to certain standards of care — generally accepted practices in the profession for diagnosing, treating and managing conditions in their patients.

"[S]ometimes they're holding us to standards that are not appropriate for situations we're presented," Moore said.

What to call it?

Some delegates ruminated over terminology, suggesting that the names of concepts are as important as the concepts themselves.

Dr. Cathy Lund, representing the American Association of Feline Practitioners, suggested adopting the British term "contextualized care" as an alternative to "spectrum of care." She emphasized that veterinarians do not intend to provide substandard care but rather recognize the diverse needs and options available to clients and their pets.

"Words matter," agreed Dr. Wendy Hauser, representing the the American Animal Hospital Association. She noted that "standard of care" is a legal rather than a medical term, and offered "continuum of care" as better capturing the goals of veterinary practice.

Research, she said, has shown that clients expect to be presented with a range of care options and have their decisions respected when determining what is best for their pets.

"So maybe it's, ‘Here are our options,' " Hauser said. " 'There's good, there's better, there's best.' "