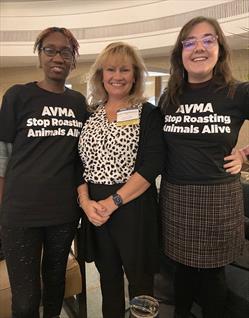

Protest in Philadelphia

VIN News Service photo

Direct Action Everywhere, or DxE, has

repeatedly protested the American Veterinary Medical Association's sanction of ventilation shutdown plus heat as an emergency depopulation method. Activists from the organization met in July outside the AVMA annual meeting in Philadelphia.

As the worst outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza in U.S. history ravages worldwide poultry farms and threatens to wipe out at least one wild bird species, veterinarians are embroiled in a battle over ventilation shutdown plus — a controversial emergency method used to cull infected flocks in hopes of containing the highly contagious virus.

The latest skirmish involved the Humane Endings Symposium, which the American Veterinary Medical Association hosted last weekend in Chicago. The AVMA denied admission to some veterinarians who have publicly denounced the organization's acceptance of ventilation shutdown plus, or VSD+.

Dr. Crystal Heath, a practitioner from California and AVMA member who campaigns against the use of the depopulation method, said she was one of a half-dozen or so veterinarians who applied to register, only to be turned away. They received emails reading: "The AVMA is not able to accommodate all the requests we have received to register for the AVMA's 2023 Humane Endings Symposium. As such, we will not register you. … You can expect a refund." The event cost between $300 and $375 to attend.

While the message did not specify that the veterinarians were barred because of their fervent stance against VSD+, AVMA officials acknowledged to the VIN News Service that that was the case.

Dr. Gail Golab, AVMA associate executive vice president and chief veterinary officer, said some outspoken critics were refused admission so that attendees, including those who raise livestock (known as producers), could share their experiences using depopulation methods without fear of reprisal. "It is absolutely critical that people feel very comfortable and that they're able to have candid and open conversations about the methods and about their application," Golab said in an interview during the three-day meeting.

Cargill, one of the largest U.S. processors of beef, poultry and egg products, and Charles River Laboratories, a pharmaceutical company, helped to sponsor the event.

"We put this and previous Humane Endings Symposia together so we can get the top experts on the science and ethics of euthanasia, humane slaughter and depopulation in the same room, and this year, we also have experts who are talking about the psychological impacts of these activities on the people who are involved in conducting them," Golab said. "We don't want anything to hinder their ability to share information. We can't have people afraid to provide information because they're afraid they will be publicly targeted."

Heath resents the notion that she and like-minded colleagues might stymie open discussion but recognizes that VSD+ attracts contempt — "for good reason," she said.

The process involves sealing a building full of animals — usually poultry or swine — by blocking off fans and ventilation systems and pumping in heat and/or humidity until temperatures rise enough to kill.

Animals may die of hypoxia (low oxygen levels) or hypercapnia (building of carbon dioxide in the blood) but most often succumb to hyperthermia, or heat stroke. "In realistic terms, death may result from any combination of excessive temperature, CO2, or toxic gases from slurry or manure below the barn," reports the AVMA Guidelines for the Depopulation of Animals.

In this environment, birds may linger as long as eight hours. Because temperatures typically are hotter in swine facilities, pigs generally take less time to die. The method was used on pigs in 2020, when Covid-19-related slaughterhouse disruptions caused a backlog of about 600,000 hogs in Iowa, creating tough choices for farmers. Many turned to VSD+ to cull their herds, drawing outrage from the public.

The impact of AVMA's stance

The AVMA is not a regulator but influences government standards. The organization's best-practices guidance on depopulation is woven into regulations by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. For that reason, the organization is under heavy pressure from activists — many from within the profession — to abandon its stance on VSD+.

Letters

From Drs. Karen L Campbell, Amos Deinard, Madeline Graham, Robin Hadley, Gail R. Hansen, Crystal Heath, Barbara Hodges, Paula Kislak, Susan Krebsbach, Peter Mangravite, Ranaella Steinberg, Debra Teachout and Carrie Waters, March 1, 2023

Published in 2019, the AVMA depopulation guidelines state that VSD+ should be "a last resort" that "must only be considered when all other options have been thoughtfully considered and ruled out."

Even if the AVMA were to remove its support of VSD+ as a last resort, that would not preclude industry from continuing to use the method. However, if the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service followed suit, producers that used it might not qualify for federal compensation for animals and eggs destroyed during an emergency response.

In the past three years, numerous petitions, protests and two resolutions submitted to the AVMA House of Delegates, both of which were tabled or rejected on technicalities, have called on the organization to reclassify VSD+ as "not recommended."

Dr. Barry Kipperman, an ethicist at the University of California, Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine, said the topic has struck a "unique chord" among veterinarians, many of whom recognize inequity in the treatment of companion versus food animals.

"It's to be expected that human expediency would be prioritized over the interests of animals," said Kipperman, who's a member of an organization called Veterinarians Against Ventilation Shutdown. "What's easiest and most convenient is to rent a couple heaters and close the door to the barn.

"But realize that there are laws in many states prohibiting leaving pets in hot cars, and some that allow a Good Samaritan to break into a car to save a distressed pet," he continued. "We as a society would not sanction the killing of dogs and cats by heat stroke, but the standards are profoundly different for food-producing animals."

Golab counters that comparing a dog in a hot car to the use of VSD+ is disingenuous because the circumstances are vastly different. While many view VSD+ as brutal, the AVMA Panel on Depopulation finds that — at least for now — the method must remain an option for producers who need it to depopulate large numbers of animals in extreme circumstances. The organization is guided by science and data, she said, and when better methods become available, "the AVMA will preferentially support those."

She added: "People are incredibly passionate about these issues, and if they weren't, I'd be concerned. But I think passion can also be blinding. … I think it is very difficult for many people to conceive of the need of within 24 hours to potentially kill a million-plus birds. I totally understand why people would have a hard time with that."

'The least bad choice'

Federal anti-VSD legislation

The AVMA depopulation guidelines state that "the use of less preferred methods [such as VSD+] should not become synonymous with standard practice."

The USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service states much the same, permitting the use of VSD+ in emergency situations on poultry and swine farms so long as other mass-depopulation methods are unavailable, or a disease poses a threat of significant transmission. Per USDA rules, outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI), which kills 90% to 100% of infected birds within 48 hours, qualify.

The recent rash of avian flu has been difficult to contain, experts say, because it has spilled into wild birds, a newer development that makes future outbreaks more likely due to migration. Researchers have so far documented infections in 51 wild bird species. While domestic birds may catch avian flu through contact with wild birds, it's more often spread via contaminated fecal matter carried on the shoes of people working with poultry.

Little can be done to save those infected. "HPAI causes severe disease, is associated with a high mortality, and is a foreign animal disease in the U.S. with no available vaccine," reports the American Association of Avian Veterinarians. Infected birds "are required to be depopulated."

One mechanism for speeding up the depopulation process, government officials say, has been VSD+, which they credit with culling large flocks within hours. Dr. Julie Gauthier, assistant director for poultry health at USDA APHIS, said as much in October during the National Meeting on Poultry Health, Processing and Live Production, observing that farm-to-farm transmission of the virus is much lower than it was during a wave of avian flu that destroyed some 50 million birds across 15 states in 2015.

"The major difference is rapid depopulation," she said.

USDA APHIS foreshadowed the heavy use of VSD+ in a 2016 postmortem of the 2014-2015 outbreak, when producers predominantly used one of two methods to destroy their flocks: foam made of air, foam concentrate and water; and containerized gassing, in which birds were placed in containers and carbon dioxide was introduced. The agency characterized these techniques as "problematic" or "extremely slow" on premises with hundreds of thousands or millions of birds, averaging 6.4 days from disease confirmation to depopulation on commercial farms and 4.1 days for backyard premises.

It took 15.4 days, on average, to depopulate commercial flocks of egg-laying hens, the report said.

Since early 2022, more than 57 million birds have been depopulated across the United States due to avian flu, the government reports, leading to a spike in egg prices as supplies grow scarce. More than 85% were culled in depopulations that used VSD plus heat as their sole method or as one of multiple methods, according to USDA data.

Typically, the USDA expects an infected farm to cull exposed flocks within 24 to 48 hours — a window that doesn't allow for many options. "We're not talking about real choices," Golab said. "We're talking about having to make the least bad choice."

That still fails to justify the use of VSD+, critics say, because other, more humane options exist. Some are laid out in the AVMA's depopulation guidelines, such as carbon dioxide, foam and electrocution, which was used in the 1990s to cull 700,000 pigs to stem an outbreak of swine fever in the Netherlands.

But those options have practical limitations. Foam, for example, can require time to ship and a large water supply to activate. The same is true of carbon dioxide, which was not in ready supply during the pandemic-related culling of swine in Iowa in 2020. "You couldn't get it anywhere," Golab said.

Such details explain why it's important that producers and the AVMA have open and candid communication, she said, "so we can see what works and what doesn't, in a real-world situation."

Who gets a seat at the table?

In an email to VIN News, AVMA President Dr. Lori Teller echoed Golab's concerns that the Humane Endings Symposium be conducted in a "respectful and constructive" manner, away from the presence of activists. She alluded to protests of the past, such as when pickets gathered outside the home of AVMA CEO Dr. Janet Donlin; or earlier this month, when protestors appeared inside the venue of the AVMA House of Delegates meeting in Chicago, wearing black T-shirts imprinted with "AVMA stop roasting animals alive."

"Unfortunately," Teller said, "some of those who have views that differ from the approach taken by the AVMA's current humane endings guidance have chosen to be disruptive in the way they express those views."

Heath doesn't believe the actions of groups such as Direct Action Everywhere, which was responsible for picketing Donlin's home, should reflect on veterinarians who share concerns about VSD+.

"It seems like the AVMA is weaponizing the language of safe spaces" to keep out dissenting opinion, she said. "Contrary to the AVMA's insinuation, my and my colleagues' actions — writing emails to our delegates, following procedures to introduce a resolution by petition, and publishing a peer-reviewed paper — is not disruptive. … Constructive criticism can help to improve the organization."

The paper she referred to is "The Rise of Heatstroke as a Method of Depopulating Pigs and Poultry: Implications for the U.S. Veterinary Profession," co-authored by Dr. Gwendolen Reyes-Illg, a relief practitioner in Milwaukie, Oregon, who works with the farm animal program at the Animal Welfare Institute. Reyes-Illg said she registered for the Humane Endings Symposium in early December and submitted an abstract of the article to present, which the AVMA rejected.

Shortly after, the paper was published in the journal Animals. Reyes-Illg, who authored the piece with three other veterinarians and an animal welfare scientist, says she was disheartened when the AVMA decided to revoke her registration for the symposium.

"I had set up meetings with multiple researchers and other veterinarians," Reyes-Illg said. "Temple Grandin just devoted a chapter that covers depopulation in her new book and wanted to talk about my paper."

New ways to mass depopulate

Grandin, a world-renowned animal scientist and agriculture engineer, attended the symposium as a member of the AVMA Panel on Humane Slaughter, which authors guidelines on the topic. In her book Routledge Handbook of Animal Welfare, she writes that there are some "extremely stressful and cruel methods that must never be used … and turning off the ventilation in a building and allowing the animals to die from heat stress" is one.

Reached by phone at her home near Colorado State University's campus in Fort Collins, Grandin said emphatically: "As far as I'm concerned, ventilation shutdown is an absolute no-no for pigs. The AVMA knows my stance on this."

As an alternative to VSD, she's developed a portable system mounted on a 30-foot flatbed trailer that uses the electrocution techniques of slaughterhouses.

Pigs are funneled into the trailer on a chute and placed in a restrainer that carries them toward hanging paddles with which the animals are electrocuted. According to a study conducted by the University of Nebraska Department of Animal Science and published by an industry group, Pork Checkoff, the pigs die within three seconds: "By introducing the current across the head, instantaneous unconsciousness occurs, and the body achieves fibrillation (cardiac arrest)."

Martha Smith-Blackmore and DxE activists

Twitter screenshot

Dr. Martha Smith-Blackmore, a delegate from Massachusetts, caused a stir last month when she met with protestors during the AVMA House of Delegates in Chicago. She

tweeted a photo of herself flanked by activists Cat Roberts (left) and Jessica Castellanos (right) and said, "I support a peaceful protest, the changing of systems that cause animal suffering, social justice harms and devastating damage to our environment."

Lead investigator Benny Mote, an animal scientist, praised the contraption as a method for swiftly killing pigs that weigh from 125 pounds to around 600 pounds. It's "extremely quick and bloodless …" wrote Mote, assistant professor and extension swine specialist. "All told, this is a safe, highly effective mobile unit that can perform hands free single step electrical euthanasia with minimal staff needed and to perform a necessary task in the most humane and mentally acceptable manner possible."

Anyone may copy Grandin's invention; the patent she once had on the system of paddles it uses expired long ago. Grandin said she hopes producers and government agencies will adapt the design for their own uses.

"I have zero financial interest," she said. "I want people to be able to replicate it for use on their farms. This is something you could put together for $100,000, and as far as I'm concerned, it's the only way to go."

A living document

Golab said Grandin's system, as well as other tools, such as high-expansion nitrogen gas-filled foam, could be up for consideration by the AVMA Panel on Animal Depopulation, a group comprised of more than 60 experts who review scientific literature on the matter and consult a network of working groups to extract new and relevant information.

AVMA policy, Golab said, calls for all reports on euthanasia, slaughter and depopulation to be formally reviewed at least every 10 years. "But we can, and do, update these any time, because they are living documents."

"We get data from a variety of sources," she emphasized. "And quite honestly, there's so much respect and trust in these documents that people actually share proprietary information to help us develop them."

Right now, the AVMA is engaged in a formal review of its humane slaughter guidelines, and the depopulation guidelines look to be next.

Golab advises those seeking to get rid of VSD+ to come up with equally available and viable alternatives. "We're very careful to provide options," Golab said. "We might prefer to use CO2 but have situations where it might not be available."

Because avian flu moves so quickly through birds, for example, "we have a limited period of time to depopulate these animals to prevent other animals from becoming ill," she said. "What you don't want to do is provide such prescriptive guidance that it can't be practically applied or adjusted to fit the needs of a particular situation."

All the same, the pressure is on to eliminate VSD+ as an option. Dr. Cia Johnson, director of the AVMA Animal Welfare Division, indicated that during an International Symposium on Animal Mortality Management in June in North Carolina. In a talk attended by producers and veterinarians, she asked that they share with the AVMA their experiences using depopulation methods.

"We need data from you," Johnson implored from the podium. "Even if it's not published, if it's a case report, if it's proprietary data. The panel needs it. Some of these methods are at risk of leaving the guidelines. I think you probably have an idea of what those methods might be. We need data to support them staying in the document."

Feb. 3 update: Sen. Cory Booker announced yesterday that he introduced a new version of the Industrial Agriculture Accountability Act.

Listen to VIN News Service reporters discuss a controversial method of mass culling livestock