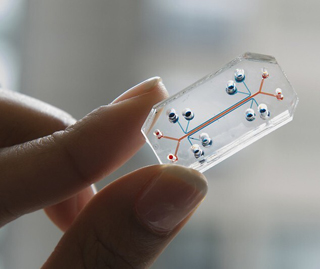

Organ chip

Photo courtesy of Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, Harvard University

The FDA Modernization Act of 2022 would eliminate the requirement that all drugs being developed for humans be tested first in animals. Possible alternative testing tools are silicon microchips that imitate the structure and function of organs. The chips are embedded with hollow tubes lined with cells from human organs, and through which nutrients, blood, medications and other such substances can be pumped.

For nearly 84 years, the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act has required that any drug intended for use in humans be tested in animals before clinical trials in people. That mandate could be reversed this summer if Congress passes a package of U.S. Food and Drug Administration reforms as expected.

The legislation does not ban animal testing. Rather, it allows the use of alternatives — such as organ-chips that recreate in a microchip the physiology of the human body — that are said to be better than animal models for assessing drug safety and effectiveness in humans.

“Our drug development paradigm needs a reboot, and this bill moves us in that direction in one simple but meaningful way,” Rep. Vern Buchanan of Florida, lead sponsor of the FDA Modernization Act of 2022 said in a press release. “Animal tests, in large part, are not predictive of the human response to drugs, with very high failure rates when the drugs go to clinical trials.”

Introduced in the Senate and House as standalone bills, the FDA Modernization Act was later added by health-committee leaders in both chambers as amendments to broader FDA-related legislative packages. These larger bills are considered must-pass because they contain provisions that update and reauthorize user fees paid by pharmaceutical companies that account for 45% of the FDA's budget. If the fees aren't reauthorized by mid-August, the agency could begin sending out furlough notices to employees. The prior authorization expires Sept. 30.

Strong bipartisan support carried H.R. 7667 through the House on June 9 by a vote of 392 to 28. The related Senate Bill, S. 2952, cleared the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee on June 14 by a vote of 13 to 9.

‘Morally and scientifically superior'

A bevy of animal welfare groups, biotech companies, medical associations and patient advocacy organizations have endorsed the legislation.

Wayne Pacelle, president of the lobby group Animal Wellness Action and a proponent of the FDA Modernization Act, said the strength of the legislation is that what's good for animals is also good for public health.

“Between 90% and 95% of drugs found safe in nonclinical tests fail during human clinical trials due to toxicities not predicted by animal tests or because of lack of efficacy,” Pacelle said.

Those failures stymie research, extend timeframes, increase costs for drug developers and disincentivize research on drugs for rare conditions. Embracing new, non-animal test methods, Pacelle said, will speed development timelines, provide more reliable results and lower failure rates.

Bill supporters also believe removing the animal-testing requirement will fuel more development of human-based biological alternatives such as organ-chips and foster greater acceptance of what Pacelle calls “morally and scientifically superior” testing methods.

The legislation tracks with developments at the FDA, which has been investing more resources and pursuing research into alternatives that eliminate the need for experimental animals or reduce their numbers.

Dr. Michael Nance, a zoo veterinarian in Texas, expressed support for the move in response to a 2019 VIN News Service report on an FDA effort to reduce animal testing, including when the drugs under development are meant for animals of the same species.

Posting on a message board of the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of VIN News, Nance wrote:

“None of us are comfortable with the idea that 100 green iguanas are subjected to X, monitored and evaluated to physiological and clinical response, euthanized and examined by histology, etc., in order to determine a safe drug or method of treating disease, pain, whatever, [with] [t]he results only directly applicable to iguanas with similar signalment and husbandry [and] [s]omewhat applicable to hopefully a majority of green iguanas. And maybe extrapolate-able to other iguanidae, and less so other lizards, and even greater leaps to other reptiles.

“It is better than nothing, of course, but the 100[s] (or thousands) of experimental green iguanas might have a different opinion if they were able to express their opinion.”

The FDA's budget request for the fiscal year that begins Oct. 1 includes funding for a comprehensive strategy for alternative methods of product testing "... to reduce animal testing through the development of qualified alternative methods and spur the adoption of methods for regulatory use that can replace, reduce and refine animal testing," also known as the 3Rs.

The 3Rs are a humane framework for experimentation in animals developed by William Russell, a zoologist, and Rex Birch, a microbiologist, in the 1950s, and since widely adopted by academia, industry and government. They are:

- replacement: avoiding or replacing the use of animals, such as with computer models

- reduction: using as few animals as possible to get sufficient data

- refinement: modifying husbandry and procedures to minimize pain and distress to experimental animals

Under current FDA rules, it is impossible to avoid using animals altogether.

There is no definitive count of animals used in drug testing each year, according to Pacelle. He explained that some species, such as mice and rats, are not required to be counted, and those that are counted are not categorized by the type of testing, such as drug development versus testing chemicals or cosmetics.

“Estimates are made of between 50 and 100 million animals used each year globally, and the use of animals for drug testing is the lion's share,” Pacelle said. “The U.S. total may be half that global figure.”

What is known is that in 2019, more than 58,000 dogs and 68,000 nonhuman primates were used at regulated animal research facilities, according to an annual U.S. Department of Agriculture report, which also gave counts for cats, guinea pigs, hamsters, pigs, rabbits and sheep.

Considering such numbers, there are those who believe the current measure doesn't go far enough.

“Some people want to see a ban on animal testing,” Pacelle said. “We made a decision not to go for that because animal testing has been the construct for a long time, and regulators and drug developers need to transition over time from that strategy.” He added that expanding human-based biological testing systems will go a long way toward reducing the number of animals used in experiments, even without a ban.

The two FDA reform packages diverge in some provisions, so after the Senate passes its version, it will need to be reconciled with the House version. Some elements may be revised or disappear from the final bill.

Pacelle said it's unlikely the testing provision would be jettisoned, since the language is similar in both bills and has broad support.