Mikey

Photo by Dr. Wendy Smith Wilson

Dr. Wendy Smith Wilson relies on a drug combination that includes xylazine to calm her horse Mikey for visits from farrier Randy Dover. Illicit xylazine combined with opioids is a factor in a growing number of drug overdose deaths in the United States.

Mikey is a cranky 16-year-old gelding who, more and more, doesn't like having his feet handled. That makes visits with the farrier tough on all involved. So his owner, who happens to be a veterinarian, worked for several months to concoct a drug cocktail to calm the horse, always starting with the sedative xylazine.

"We finally hit on a combination the last time of xylazine plus acepromazine plus butorphanol in just the right amount," said Dr. Wendy Smith Wilson, who lives in Ohio, near the West Virginia border. "It got him sleepy enough that he is amenable to being trimmed, but he wasn't falling over, and it lasted long enough ... to get through all four feet."

Xylazine has been an essential tranquilizer, sedative, analgesic and muscle relaxant administered by large animal practitioners as well as laboratory animal veterinarians for decades. It is also used in cats and dogs, although to a lesser extent. Now, the nonopioid compound is drawing scrutiny in the United States for its role in a growing number of opioid overdose deaths in people.

Increasingly, drug traffickers and dealers are combining xylazine with fentanyl, cocaine, benzodiazepines and heroin to enhance their psychoactive effects and extend the length of the high.

A study published last month in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence found xylazine to be increasingly implicated in overdose mortality, rising from 0.36% of deaths in 2015 to 6.7% in 2020 in 10 jurisdictions around the country. The greatest xylazine prevalence was observed in Philadelphia (25.8% of deaths), followed by Maryland (19.3%) and Connecticut (10.2%).

Authors of several papers about illicit xylazine, known on the street as "tranq," warn that estimates may be an undercount since many jurisdictions do not routinely investigate for xylazine in overdose deaths.

There is no indication that xylazine is being diverted from veterinary providers, clinics or pharmacies, according to a memorandum from the Illinois Department of Health.

Veterinarians know: Xylazine is not for humans

Xylazine was first synthesized in the 1960s by Bayer Co. in Germany for use in reducing high blood pressure. It was not approved for use in people due to some hazardous side effects, including sedation, low blood pressure and slow heart rate. However, it has been deemed safe for some animals.

Various species respond differently to the same dose per body weight, explained Dr. Christy Corp-Minamiji, who works in communications for the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession and parent of VIN News.

"For instance, if I give a 1,500-pound cow the same amount of xylazine that I would use for standing sedation in a 1,500-pound horse, the cow will fall over and likely have severe respiratory suppression," she said. "As our toxicology friends would say, 'The poison is in the dose.' For humans with xylazine, that threshold is even lower than for a cow. Like almost none."

Today, experts worry xylazine can increase the chances of a fatal overdose when combined with drugs like fentanyl because it might exacerbate the respiratory depression that opioids cause. Making matters worse is the fact that naloxone, a drug used to reverse opioid overdoses, is ineffective against xylazine.

That xylazine is dangerous for people is well-known to veterinarians.

"When I was in school and was learning about anesthesia in 1996, they were like, 'Never get injected with xylazine because you can die,' " said Smith Wilson, who also works for VIN. "It's made very clear to us from day one, this is not a medication you want to screw around with in humans."

Corp-Minamiji had her own brush with this reality. In the early 2000s, when she was working as an equine practitioner in Northern California, reporters contacted her to learn about xylazine after a Sacramento woman was accused — and eventually found guilty — of murdering her husband by injecting him with xylazine.

"The press originally just said she used a 'horse tranquilizer' without naming the drug or mentioning that humans are particularly susceptible to its ill effects," recalled Corp-Minamiji. "I kept having to explain to clients that drugs behave differently in different species and that xylazine is generally extremely safe in horses."

Xylazine in animal medicine

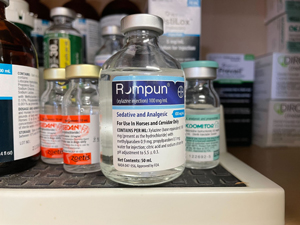

Rompun

Photo by Dr. Wendy Smith Wilson

A bottle of the veterinary medicine Rompun, or xylazine hydrochloride, sits on a shelf at an animal clinic in southern Ohio, where it is generally used as a sedative or analgesic for horses and goats. On the right is a bottle of dexmedetomidine, a related compound. On the left, are two bottles of atipamezole, a drug that is used to reverse the effects of xylazine and dexmedotomidine in animals.

Xylazine hydrochloride under the brand name Rompun was first approved for use in dogs, horses and hoofed ruminants by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1972. Another xylazine product, Anased, approved in 1988, added cats to the species list.

Dr. Dawn Boothe, a specialist in small animal internal medicine and veterinary clinical pharmacology, explained that xylazine interacts with receptors that prevent the release of chemicals in the body that are responsible for a lot of actions, including those associated with pain, muscle activity and central nervous system stimulation. "Because the chemicals are not released, these effects do not occur," she said.

Xylazine is often used in combination with other chemical sedatives to provide a level of general anesthesia that can be used for surgical procedures. "By itself, it is not sufficiently sedating, nor does it provide enough analgesia and, as such, generally is not used alone," Boothe said. "However, in combination, it has been effective, particularly because it contributes a lot of analgesic effects."

There are several compounds, among them atipamezole, that are used to reverse the effects of xylazine in veterinary patients. Veterinarians discussing the overdose problem on a VIN message board wondered whether atipamezole could be used to help people who overdose.

The short answer is no. Atipamezole is not approved for use in humans.

Chelsea Shover, an assistant professor-in-residence at the University of California, Los Angeles, David Geffen School of Medicine and a co-author of the study on the rising presence of xylazine in overdose deaths, said by email that there doesn't seem to be much of a public health need for a reversal agent specific to xylazine.

"Based on currently available information, in the United States, essentially all fatal accidental overdoses involving xylazine also involve fentanyl," Shover said. "We are not seeing accidental overdoses involving only xylazine, so that is the reason why the xylazine-specific reversal agents aren't a high priority at this time. Put another way, many of the fatal overdoses where xylazine is detected would likely have been fatal anyway due to the other substances (e.g., fentanyl) onboard. So a xylazine-reversal medication wouldn't have changed the outcome."

In addition, there is some concern that using drugs like atipamezole in humans might do more harm than good. "The concern boils down to … potentially overdoing it and causing uncontrolled seizures,” she said.

With or without xylazine, drug-related opioid deaths are on a steep rise. Nearly 108,000 people died from overdoses in 2021, according to provisional data published this month by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Driven by an ever-worsening fentanyl crisis, overdose deaths increased 15% over 2020, a year that saw a whopping increase of 30% over the year before.

Feb. 28 update: The FDA announced it is giving increased scrutiny to imports of xylazine, screening all shipments of the product in raw or finished form to verify that it is properly labeled, not adulterated and en route to legitimate supply chains for the veterinary marketplace. Products without proper labeling or paperwork may be detained and potentially refused entry into the U.S.