Novel One Health collaboration helps vulnerable young adults, tests integrated model

Youth clinic 1 288

VIN News Service photo

Hannah Rose Cohen (left) and Kennedy Brooks, fourth-year veterinary students from Washington State University, inspect Rowdy's ears at the One Health Clinic for homeless young adults and their pets.

Every evening, some of the estimated 1,500 young adults who are homeless in Seattle drop by a center downtown where they can score a hot meal and companionship, shoot a game of pool, take a shower, do laundry and even spend the night. Those with pets visit on select evenings for another, more improbable reason: to attend a clinic where they can receive veterinary care for their companion animal and health care for themselves.

The center is run by New Horizons, a nonprofit social services organization. Every other Wednesday, New Horizons hosts what's called One Health Clinic, which brings together a veterinarian and veterinary students, a nurse practitioner and students in health sciences (including medical, nursing, social work and nutrition) who treat the young adults and their pets as family units.

This means owner and pet stay together during the animal wellness visit and the human health visit, which take place in adjacent upstairs rooms at New Horizons. The veterinary and human health teams share information and insights for care decisions and research. Due to laws protecting human patient privacy, most of that information flows from the veterinary side to the human health side.

This clinic is the only one of its kind in the country, according to Dr. Peter Rabinowitz, a physician and professor of environmental and occupational health sciences at the University of Washington in Seattle. Rabinowitz is the director of the UW Center for One Health Research, which spearheads the clinic with Washington State University's College of Veterinary Medicine. "It's the only one that is really treating human patients and veterinary patients as a unit, not separately," he said. One Health is the concept that the health of humans, other animals and the planet are intertwined.

"There have been a lot of taboos about animals and people being in the same health-care facility," Rabinowitz said, referring to concerns about infections passing between animals and humans, adequate disinfection, and the possibility of animal-related injuries. "But we find that it is actually pretty doable," he said.

Letters

In partnership with Neighborcare Health, a community organization that operates a human health clinic twice a week at New Horizons, the One Health Clinic launched as a pilot in October 2018. Now an established service, it opens a door to health care for 18- to 26-year-olds who may not trust the medical establishment themselves but are willing to see a veterinarian for a beloved pet.

"At this clinic, we've seen a lot of new human patients because that veterinary care was available to them," said Vickie Ramirez, coordinator of the Center for One Health Research. "They may come in for shots for their dog, but end up at least having a talk with a nurse practitioner or an MD. They are now in the health-care system and they are returning."

Rabinowitz_OneHealth 288

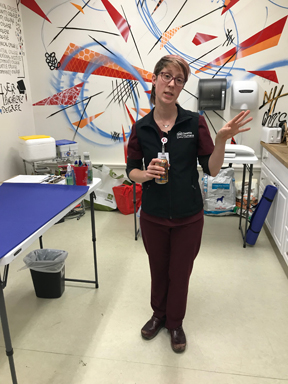

Photo by Gemina Garland-Lewis

Physician, health sciences professor and director of the University of Washington's Center for One Health Research, Dr. Peter Rabinowitz imagines a time when veterinarians and physicians providing family care alongside each other is the norm.

In its first year, 32% of the human patients at the One Health Clinic had not accessed care in the previous two years, according to Christie Cotterill, associate director for WSU development and alumni relations, who raises funds to support the veterinary side. She said the clinic has completed 116 veterinary exams since it began. In addition, attendance at the Wednesday night clinics, which includes a humans-only Youth Clinic on alternating Wednesdays, has doubled since the One Health Clinic began.

'Family' medicine

The entrance to the clinic's health services does not look like your usual waiting room. On a recent evening, young people chatted and ate a free meal at a half-dozen round tables in New Horizon's pet-friendly drop-in center. The aroma of spaghetti sauce wafted from a cafeteria-style kitchen. Someone from the clinic circulated with a sign-up sheet.

The crowd was thin, about half its normal size, according to Kat Wynn, communications and marketing manager at New Horizons. Wynn attributed the low turnout to below-normal temperatures and recent snowfall. She said it's common for young people who lack stable housing to find shelter early in the day and stay put when the weather is especially bad.

This cold night, only one pet owner braved the elements to bring in his white and black Aussie-mix, named Rowdy, for an upset stomach and an irritated ear. An average clinic sees about five animals, but as many as 11 have shown up in one session. The patients are mostly dogs and cats, but not exclusively; there's been at least one ferret and one pigeon.

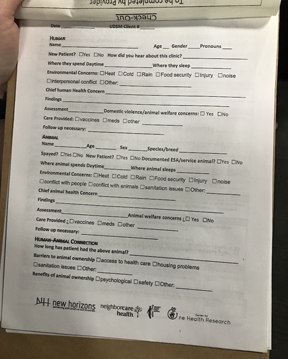

OneHealth form 288

On most One Health Clinic nights, the routine goes like this: Over the course of three hours, clients with pets are escorted upstairs. There, among a warren of cubicles that are the daytime offices for New Horizons staff, one of two UW medical student volunteers meets each family unit. The volunteer guides the people and their pets through the various steps, starting with finding a quiet spot to help them fill out paperwork. One of the forms illustrates the novelty of this clinic: It asks about the person, then the pet, then the connection between them. For example, regarding "Benefits of animal ownership," the form offers as possible answers "psychological," "safety" and "other."

Sophie Blackburn is a first-year medical student also pursuing a doctorate in bioengineering. A volunteer at the clinic since October, she described her role as tracking the human-animal connection.

"I ask a bit about the bond between the two," she said. She gently inquires if their pet is an obstacle to finding housing and how weather conditions may affect either or both. She also simply observes how the clients handle their pets.

"You can often see the clear attachment between the person and the animal," Blackburn said. One woman brought in her dogs and couldn't watch them get shots because she hated to see them in pain.

Blackburn often is struck by the differences in the way some people talk about their animals versus themselves. They will volunteer lots of information about their pet but in the human exam "they will almost retreat," she said.

Katie Schneier, a clinic administrator for Neighborcare, said that by getting to know the clients' animal companions, providers are able to get to know the clients better and build trust by showing interest and offering a needed service. "It gives us another way to interact with patients that allows them to get to know us in a way they feel safe," she said. "We've seen them transform their relationship to medical care through that."

The veterinary team is paid for by WSU through a donation from the Banfield Foundation. The UW Center for One Health Research has been contributing staff time for outreach and development of clinic protocols. Rabinowitz is a volunteer preceptor for the UW health sciences students. Neighborcare Health, which operates more than 30 clinics serving low-income and homeless individuals and families in the Seattle area, is funded by insurance reimbursements, private donations and government grants.

History of One Health

The One Health idea goes back at least to the 19th century, when the medical profession became aware that some infectious diseases can be transmitted from animals to people. Dr. Calvin Schwabe, a veterinary epidemiologist at the University of California, Davis, School of Veterinary Medicine, coined the term One Medicine in 1964 to emphasize the parallels between veterinary and human medicine, and to emphasize the need to collaborate to cure, prevent and control illnesses that affect humans and non-human animals alike, according to a U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention timeline.

It took decades for the concept to catch on, but in 2007, the American Medical Association adopted a resolution calling for increased collaboration between the human and veterinary medical communities. In the ensuing 10-plus years, One Health has become a global effort aimed at fighting pandemics. It also has expanded to explicitly include environmental health in the interdependence matrix.

The UW Center for One Health Research has been around since 2014 and focuses on several facets of One Health, including zoonotic and emerging infectious diseases, antibiotic resistance, interactions between humans' and other animals' microbiomes, the occupational health of animal workers, sustainable animal agriculture and the human-animal bond.

"One Health in the U.S. academic setting has been pushed a little more on the veterinary side than the human side," Rabinowitz said. "[This clinic] is a way to really bring human health sciences students into contact with veterinary students."

Entering The Nest

Youth clinic 2 288

VIN News Service photo

Dr. Katie Kuehl, clinical instructor of shelter medicine for WSU based at Seattle Humane, oversees veterinary students working at the One Health Clinic as part of their clinical rotation in Seattle.

With paperwork complete, the medical student escorts the pet and pet owner to an area known as The Nest because it converts to a 15-bed shelter every night. A portable examination table sits in a "living room" and kitchenette space. Set up on shelves and a table are a portable pharmacy, equipment including a scale, ophthalmoscope/otoscope, a Wood's lamp (a handheld diagnostic tool that uses ultraviolet light in the diagnosis of bacterial or fungal skin infections), and a vaccine cooler, syringes, and needles. Donated food, treats, collars and other pet supplies spill out of bags and boxes. A doorway leads to the Neighborcare Health office, where most of the human health consultations occur.

Dr. Katie Kuehl leads the veterinary team. A veterinarian and clinical instructor of shelter medicine for WSU, Kuehl usually brings along two fourth-year students who are doing a clinical rotation at Seattle Humane, where she is based.

Kuehl said her team provides basic wellness care at the One Health Clinic, including treating skin issues, allergies, minor injuries; giving vaccinations, deworming medication and flea preventative; encouraging spaying and neutering; and offering behavioral tips along the way.

In addition to hands-on experience and work in the community, Kuehl said, "I think it's really important for students to see that even if you can't order all the gold standard diagnostics, there are still ways you can improve the quality of life for that patient and for that family and can meet that family's needs."

The students also are exposed to a population of clients different from those who typically visit WSU's state-of-the-art teaching hospital. "It's eye-opening for a lot of folks," she said.

Kuehl, too, has learned from the experience. It challenges her to remember to think beyond the animal alone and to consider the pet and human as a unit.

"We can't just treat the one without thinking about the other very effectively," she said. While housing insecurity has obvious implications for the health of people and their pets, the interplay between person, pet and their living circumstances is important no matter the income. Say, for example, you want to put a dog on an anti-seizure medication that needs to be given three times a day, Kuehl said, it's critical to recognize that an owner who works outside the home might not be able to handle those intervals.

While the veterinarian and veterinary students examine the pet and talk with the owner, the medical student listens for anything that might be relevant when it comes time for the owner's meeting with the human-health practitioner. Blackburn remembered one person who came in with a cat exhibiting new aggressive behavior after a traumatic event. The veterinary team offered ideas on how to manage the cat's behavior and rebuild trust. The situation with the cat was also important for the human health-care team to know about so they had a fuller understanding of the pet owner's daily life.

"We think a lot of important stuff pops up during the veterinary visit," Rabinowitz said. He gave the example of a human and an animal living together in a tent. The animal might exhibit problems relating to moisture and mold, flea infestations or exposure to irritating fumes — all of which can create health challenges for human, as well.

'Eye-to-eye' contact

Sporting a red bandana, a sweater and a raincoat, the evening's sole animal patient Rowdy got a lot of attention. (The VIN News Service was not able to interview Rowdy's owner because he had not signed a consent form, which Neighborcare is required to obtain by law to protect the privacy of its patients and New Horizons clients.) He's been to the clinic several times because of an allergy that manifests as skin/ear disease.

"This is a frustrating condition for all owners, but especially when resources are limited for fancy food and expensive medications," Kuehl explained. She is working on a multi-pronged approach to control symptoms by providing bags of dog food using novel proteins in case it's a food-related allergy, supplements to support skin health and treating flare-ups as they happen.

He left with one more dog coat (a donated motorcycle-style jacket he couldn't pass up), two bags of food, a couple chew toys, ear-cleaning solution and ointment, toothpaste and finger brushes, dental chews, training treats, and proof of a rabies vaccination. At some point during the visit, Anina Terry, the Neighborcare nurse practitioner, spent time with the owner (and Rowdy). She said they had a lengthy discussion about accessing human health-care services and made a plan to follow up later in the week.

This is how it is supposed to work. Before the clinic began that night, Terry told the team: "One really important thing is that people come here to access veterinary care and human health, and a lot of times the draw is care for their pet, and we support that." But, she said, "it's really important that everyone sees me." She told them it didn't have to be any more than a quick check-in whenever the moment feels right to ensure that the owner also is connected to human health-care services. She strives for an "eye-to-eye" with everyone who comes into the clinic.

Learning lessons, expanding the model

At the end of most One Health clinics, the medical professionals and students come together to talk about the evening. The discussion is part of the clinic's mission to create an environment for what Rabinowitz calls "active interprofessional learning." It's one reason he emphasizes student participation.

Medical students learn about how veterinary students diagnose and treat animals and, in turn, the veterinary students learn how medical students approach clinical problems. Sometimes the approaches are very similar and sometimes not, Rabinowitz said. For example, veterinarians are using medications, such as allergy-pathway blockers, that are not yet in use on the human side.

Kennedy Brooks, one of two WSU veterinary school students working the night Rowdy was seen, offered this assessment of the two-team approach: "There was meaningful collaboration between different professions that led to a higher standard of care than if any one profession had done a similarly intentioned clinic by themselves."

Blackburn, the medical student, observed, "We have a lot of the same concerns, like vaccinations and skin issues." But not everything aligns; for example, one big difference she cited is shelter medicine's emphasis on population control.

Another contrast that intrigues Blackburn is the veterinary physical exam, during which the practitioner has to pick up on clues the patient can't describe. "It's very interesting sometimes how little information [veterinarians] have to go on," she said, adding that this knowledge may influence her down the road. "I think sometimes the physical exam gets glossed over," she said. "Being very aware of what you are looking at; I think that's important."

With the clinic as the hub, researchers at WSU and UW are doing ongoing program evaluation, studying connections between human problems and animal problems, and defining priorities for care. One of their goals is to come up with findings that lay the groundwork for additional One Health clinics.

"We have a vision that in the future ... in addition to providing care like this for the homeless, this could be a model for primary care, as well as for other populations," Rabinowitz said. "Why shouldn't a doctor and a veterinarian work right next to each other in the same building and provide family care for both the animals and the people?"