Dr. Veronica Gventsadze 288

Photo by Peter Scheunert

Like many general practitioners, Dr. Veronica Gventsadze was uncomfortable treating rabbits, a problem she attributes to inadequate exposure in veterinary school to the sensitive herbivores.

Not long ago, if you’d asked me whether I see rabbits as patients, I would have shaken my head vigorously. No way would I touch those fragile things. Everyone knows that rabbits drop dead if you so much as look at them the wrong way. Doing no harm as a doctor meant, for me, declining to see a rabbit.

That's because I knew almost nothing about this delicate prey species. My exposure to them in veterinary school consisted of about an hour of lecture, followed by a lesson in safely picking up and carrying an uncharacteristically docile New Zealand buck who lived in the university laboratory.

Things changed when in the fall of 2016, my husband and I — much to our own surprise — adopted a rabbit. A veterinary nurse friend had shared a photo of an SPCA rabbit she’d successfully intubated (a challenge in this species) for a spay surgery. Something drew me irresistibly to this animal, entirely vulnerable under general anesthesia with a tube in her windpipe, yet noble and proud even in this state. We took her home.

I won’t compare Tilly to any other animal, as that would do an injustice to them all. Let’s just say that a rabbit’s personality is as unique and demanding as its physiology. Since bringing Tilly into our lives, I have sought out every book and every continuing-education course on rabbit medicine I could find.

I also joined online communities for rabbit owners. This was when I became aware of the huge gap between the needs of owners and the availability of veterinary care for rabbits.

So in February 2018, I launched an online petition calling on schools accredited by the American Veterinary Medical Association’s Council on Education to teach clinical competence in rabbit medicine as part of their core curriculum.

'Treat them as equals'

Starting a petition drive is not my usual style. I've spent my life trying to avoid upsetting people or rocking boats. And rabbits haven't exactly been a life passion. But multiple surveys consistently show rabbits as the third most popular pet mammal after cats and dogs. It didn’t seem right that rabbits are relatively ignored by my profession. As one petition-signer from the U.K. commented, "Rabbits are as important as cats and dogs, they are not second rate animals and vets should all treat them as equals."

The House Rabbit Society puts the number of pet rabbits in the U.S. at between 3 million and 7 million. The animal welfare organization People's Dispensary for Sick Animals, known by the acronym PDSA, estimates 1.5 million pet rabbits in the United Kingdom. A 2016 census of pet owners in Australia by the insurer PetPlan found that 4.9% of 100,000 respondents owned one or more rabbits.

Despite their popularity, or alongside of it, rabbits are extremely vulnerable to abandonment by unprepared owners who discover that this animal is not all cuddles and carrots. Many abandoned rabbits die without human protection; survivors go on to lead a feral existence. A fortunate few are surrendered rather than abandoned, or are rescued from the feral state, making them a common animal in shelters and a common patient in shelter medicine.

Several petition supporters pointed out that the lack of rabbit-savvy veterinarians inhibits people from adopting rabbits from shelters.

While the petition campaign was underway, I informally polled general-practitioner colleagues in the U.S. to get their perspective. Sixteen responded. All said they’d had little to no mandatory training in small mammal medicine, but most did see a varying number of rabbits for spay and neuter surgeries, which they learned to do from books, online resources and rabbit-savvy colleagues. Beyond sterilization surgeries, the colleagues did not feel qualified to give medical advice on rabbits. Several mentioned that they were extremely allergic to rabbits.

Those who did see rabbits for preventive care and medical problems invariably had taken a small mammal/exotics elective at university, or had attended CE courses on the subject. A few mentioned that their practices receive calls from clients inquiring whether they see rabbits, but they have to turn them down.

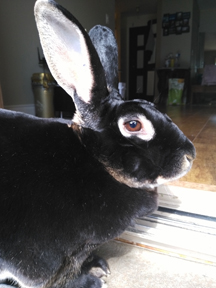

Tilly 216

Photo by Dr. Veronica Gventsadze

This animal's proud and noble presence led the author to take her home, and to become an ardent advocate for rabbits.

Many rabbit owners, having been turned down in the past or having received care inappropriate to rabbits, seek out only veterinarians with specialized training in exotic animals. (Veterinarians can become boarded specialists in exotic companion mammal practice through the American Board of Veterinary Practitioners.) General practitioners who work mostly, if not exclusively, with dogs and cats may therefore have a false belief that there are not many rabbits out there who need them. This is another reason that clinical competence in rabbit medicine should be taught in the core curriculum: Veterinary students must be made aware of the tremendous need out there.

Most veterinary schools do touch on rabbits, usually over the space of a couple of hours, whether as pets, agricultural species or laboratory animals. But this is a far cry from teaching clinical competence in the species or making students aware of the high demand.

The Council on Education, which accredits veterinary schools, does not prescribe curriculum, nor does it state which species must be included in the core curriculum. Its accreditation standards state in part: "Normal and diseased animals of various domestic and exotic species must be available for instructional purposes, either as clinical patients or provided by the institution" and the curriculum must provide "instruction in both the theory and practice of medicine and surgery applicable to a broad range of species." Further, the curriculum must provide “knowledge, skills, values, attitudes, aptitudes and behaviors necessary to address responsibly the health and well-being of animals in the context of ever-changing societal expectations.”

Let me share some of the societal expectations as expressed by people who signed the petition:

From South Carolina: "I have needed an emergency vet for my bunnies several times, and none of the emergency vets treat rabbits. All vets should have rabbit care training."

From British Columbia: "Rabbits, both as pets and livestock, desperately need better veterinarian support in Canada!"

From Virginia: "Rabbit medicine should be taught commonly and thoroughly, and not just given as a[n] overview in an exotics class. There is no reason that most vets and techs should have no idea how to properly treat rabbits."

From a long-time rabbit rescuer in California: "I have had to help train countless ER veterinarians. Also, a tremendous amount of rabbit owners do not have access to exotics vets. This means when the rabbit becomes ill they need to seek out veterinary care from what I'm calling a general practitioner, one who sees mostly dogs and cats. Most of these veterinarians do not even know the basics of proper rabbit treatment, basic protocols and the proper or dangerous medications. Again, ludicrous. Disrespectful. Dangerous. Please update your curriculum!"

From the U.K.: Failure to train veterinarians in rabbit medicine is "shocking and nothing short of animal neglect."

A number of petition supporters pointed out that rabbit medicine offers good income potential. For a profession in which many colleagues are struggling with debt and many practices are trying to stay afloat financially, this is a point worth considering.

From Australia: "In the last month, I have spent 4000 [Australian dollars] on my buns. Make sure you can profit from rabbit owners in the future. There are a lot of us!"

From California: "There are enough people with pet rabbits these days that it is worth the investment in time & money to train veterinary students in rabbit physiology, health & care. They would have enough clientele to make their money back quickly. My vet is so in demand because there aren’t enough rabbit specialists like her."

From Montana: "Our pets deserve good care and we are willing to pay for it."

The petition drew more than 11,500 signatures. Some of the signatures belong to world-renowned educators in and practitioners of exotics medicine such as Drs. Frances Harcourt-Brown, Molly Varga and Livia Benato, and veterinary nurse Jo Hinde of the U.K.-based continuing education organization Lagolearn, which is devoted to rabbit medicine. Many veterinarians — some exotics specialists and some not — signed. Most supporters were rabbit owners, including breeders.

Schools respond

In mid-May, I emailed the petition to 44 schools in North America, the U.K., Australia and New Zealand, as well as to the Council on Education. (A total of 50 schools are accredited by the COE. I skipped the few that I knew teach rabbit medicine and a few in foreign countries that posed, for me, a language barrier.) Prompted by several petition-signer comments from South Africa, I also sent the petition to the University of Pretoria’s Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, although it is not AVMA-accredited.

I was aware of two accredited schools that already incorporate rabbit medicine in their core curricula: the University of California, Davis, and the University of Edinburgh's Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies. At UC Davis, all veterinary students spend a block of two weeks studying exclusively small mammal medicine, including a dentistry lab. The school placed the course in its core curriculum after recognizing that a majority of students (80%) were enrolling in a small mammal/exotics elective. The Dick Vet provides eight lectures on rabbit medicine and two hands-on clinical lessons.

So far, 12 of the schools to which I sent the petition have responded. I’m honored to say that one, the University of Georgia, wants to discuss how they can incorporate rabbit medicine into the curriculum. I look forward to the conversation!

Many responses were positive, if unspecific. Massey University in New Zealand, The Ohio State University and Iowa State University stated that they already were considering a curriculum revision and would take the petition under advisement. Colorado State University stated that even prior to receiving the petition, they’d been discussing "the need to provide more hands-on training in rabbit medicine and surgery," and will be learning from the experience of UC Davis.

Seven schools replied that they do teach rabbit medicine in the core curriculum, and most provided details:

- Tufts University's Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine devotes five hours entirely to rabbits. While this may not seem like a lot, the school also has a rabbit-heavy and varied caseload to which all students are exposed during required clinical rotations at the teaching hospital.

- Oregon State University's Carlson College of Veterinary Medicine teaches rabbit medicine within its 4-credit (about 60 contact hours) Special Animal Medicine course that includes other laboratory animals.

- Kansas State University College of Veterinary Medicine teaches rabbit medicine within a 2-credit (30 contact hours) Exotic Pet Medicine course that includes amphibians, small reptiles, birds, fish and small mammals other than rabbits.

- University of Minnesota's College of Veterinary Medicine stated that it teaches rabbit medicine but did not specify how.

- Ontario Veterinary College, my alma mater, is now teaching Avian and Exotic Medicine in the core curriculum over two semesters. That's a huge (and to me, thrilling) change in the 11 years since I graduated.

- University of London Royal Veterinary College, known for its Exotics Service at its teaching hospital, provides all students with a variety of teaching sessions in rabbit medicine.

- The University of Queensland in Australia teaches rabbit medicine, including surgery, anesthesia and clinical techniques, throughout its five-year curriculum. They did not specify the time given to the training.

That leaves 32 schools still to reply.

The bane of exoticism

Part of the challenge in persuading schools to give more attention to rabbits could be that they are still seen as exotic pets, in the category of unusual animals with unusual needs. As obligate herbivores, they are indeed radically different from our more common carnivore pets in their physiology and drug metabolism, and as prey animals they are exquisitely sensitive to stress and vulnerable to shock. Hence, their reputation for fragility is well-founded.

But this does not make them any more unusual than horses, whom they closely resemble in physiology; or cats who, before that long ago, also were overlooked as veterinary patients.

Historically, pet rabbits are a byproduct of the meat and/or show industries, whose breeders do not always (and some never) seek veterinary attention. Rabbits are easily reproducible and fast-growing, so economically it makes more sense to cull a sickly animal than to treat it.

But once we realize how much rabbit owners love their animals, and how common they are, it makes absolutely no sense to keep calling them exotic, or to look down on them as replaceable. As a petition supporter from New York wrote, "I don't believe rabbits are exotic, they are very common and are a traditional American farm animal!"

I'd be a poor rabbit advocate if I didn't note that as companions, rabbits are not for everyone. They are most certainly not a 'starter pet,' or a low-maintenance pet for kids. Not all adults like them, or need to like them. A veterinarian friend who is highly proficient in rabbit medicine remarked that he could never keep a rabbit as a pet: They simply scare him. Their fragility and their strange (compared with dogs and cats) behavior make them unattractive to him as companion animals. I totally get that.

My thought is that in a culture that so highly values the adjective "aggressive," rabbits are a breath of fresh air, and their owners form a community that may be the closest thing to world peace.

That does not obligate us all to like rabbits. As veterinarians, we don’t have to carry the emotional burden of loving, or even liking, our patients. We need only to love medicine, to treat our patients with kindness and reverence while they are under our care, and to listen to owners. Which means that we should start taking rabbits, and their people, a lot more seriously.

About the author: Veronica Gventsadze, MA, PhD, DVM, worked as a language interpreter at business conferences and as a university professor of the humanities before gathering the courage to turn her love of science and animals into a profession. Upon graduating from Ontario Veterinary College in 2008, she settled in British Columbia, where she received her battle christening in the trenches of small animal medicine. Besides advocating for rabbits, Gventsadze brings public attention to the plight of moose and caribou, who continue to be trapped in abandoned telegraph wire in Canada's Pacific Northwest. To balance the rigor of daily work, she writes fiction, incorporating lessons learned from animals. To reach Gventsadze, contact her through her website.