Click

here for larger view

A letter mailed this spring to 2,000 proprietors of small veterinary clinics invited them to consider merging with a neighboring hospital run by VCA Inc., the largest owner of freestanding veterinary hospitals in the United States.

“By combining your practice with a current VCA Hospital, we remove the burden of day-to-day management, helping you achieve a more balanced lifestyle while you continue to practice veterinary medicine,”

the letter reads. “If retirement is what you are looking for, a merger with VCA can be your exit strategy.”

In the view of Robert Antin, president, CEO and co-founder of VCA, the letter constitutes a “smiley face” topic — a happy example of VCA supporting the veterinary community by providing financial options to its members. The solicitation, he said, is “not contentious.”

But it is.

Some veterinarians who received the letter took strong offense. One called the move “somewhat predatory.”

“It feels like a hostile takeover,” said another. “They’re taking out anybody who’s competition.”

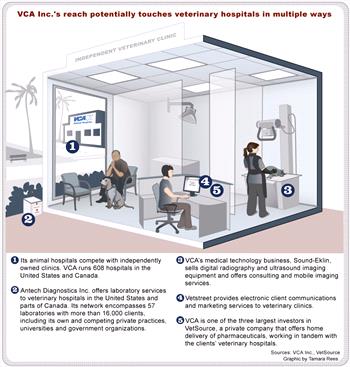

The reactions illustrate the perceived threat VCA poses to a segment of independent, small-hospital owners in the face of the company’s continual growth. In 27 years, VCA has expanded from a single hospital in Los Angeles to 608 hospitals across North America. It owns one of the two biggest diagnostic laboratories in the country; a digital medical equipment company; and a practice-communications and marketing business. It also is one of the three largest investors in VetSource, a pharmaceutical distributor.

The company workforce tops 17,000, about 3,500 of whom are veterinarians. With anticipated annual revenues approaching $2 billion this year, VCA is a giant in veterinary medicine. In many eyes, its size and reach — touching most aspects of daily clinical practice — is cause for concern and suspicion.

VIN News Service photo

In a wide-ranging interview at company headquarters in Los Angeles, VCA co-founder, president

and CEO Bob Antin talked about the company origins, its culture, public image and industry challenges.

Referring to a national decline in patient visits, he said, “If we collectively don’t figure out how to drive

more people into hospitals, not just VCA, we’re all in trouble.”

Inside VCA, the view is completely different. Executives see their corporation as a collegial and conscientious steward of veterinary medicine, an avid supporter of training via a large internship and residency program, and a conduit to capital that provides flexibility and financial options for the profession as a whole. Some outside observers share the view of VCA as a benign force.

The polar perspectives are underscored by Antin’s bewilderment upon hearing of indignant responses to the acquisitions letter.

“Out of all the reactions that I would think of, the one you describe would not even come to mind,” Antin said during an interview at his sunny office near Santa Monica, California.

Speaking of VCA’s intentions, Antin said, “All you’re doing is giving options. If by mistake you wrote the letter to the wrong person, I apologize. … You don’t want the choice, don’t take it. Feel honored (to have been asked).”

The letter represents a new strategy for continued acquisitions, according to Neil Tauber, a VCA co-founder and senior vice president of development. Historically, the company sought only larger practices, those with annual revenues of $1 million or more. “We’ve tried in recent years something new, which is merging smaller practices into larger practices,” he said.

Like Antin, Tauber described the solicitation as providing a financial option for owners of independent small hospitals who are amenable to selling. “It’s created an opportunity for them,” he said, “whereas in the past, they were unable to sell to a corporate buyer because corporations tend to look for about the (larger) same-size practices.”

The solicitation was intended to be friendly, Tauber said, paraphrasing: “ ‘We want to offer you this opportunity because it makes sense.’ It doesn’t say, ‘We want to drive you out of business.’ ”

Antin acknowledged that different individuals may perceive the same facts in distinctly different ways. Married with a 25-year-old son and 23-year-old twin daughters, Antin allowed, “I’m sure when I tell (one) daughter I love her, she hears it differently from the other.”

‘Manny, Moe and Jack’

From the beginning, VCA aroused mistrust in the veterinary community. For starters, none of the founders is a veterinarian.

Antin and Tauber came from human health-care administration. Arthur Antin, older brother of Bob Antin, was an alternative-school teacher and administrator before switching to the health field. Art, Bob and Neil grew up in New York City in families of modest means. Art and Neil met as young men on a beach volleyball court on Long Island; Art introduced Neil to Bob. They discovered a shared passion for sports and an interest in managing the business of health care.

VIN News Service photo

Art Antin, senior vice president and chief operating officer, says chance inspired the VCA founders to pursue the business end of veterinary medicine. Getting to know the original owners of West Los Angeles

Veterinary Medical Group was pivotal: “My bet is if we’d never met them and never walked into their practice and never saw the potential of what veterinary medicine could be like, we never would have gotten into the business.”

In the mid-1980s, Bob, Art and Neil started a company called AlternaCare, which operated outpatient surgery centers, at the time a new concept. “Neil was involved in rolling up dental centers, which obviously overlapped with the concept of (establishing) outpatient surgery centers, which also overlaps with what it is we’re doing now,” Art said.

The idea of outpatient surgery took off, and AlternaCare was bought out in 1986, fewer than three years after the entrepreneurs, then in their 30s, started it.

The trio mused where to venture next. “We thought we could start a company, because we’d done it once,” Art said. But what kind? One day on an airplane, he overheard women in the seat behind him talking about finding a good veterinarian. Aha! he thought.

“I heard the word ‘veterinarian’ and that was health care,” Art said. “You know how you’re in the right place at the right time? … Had I been in another seat, another row, it might never have happened.”

But the earliest steps were not encouraging. The entrepreneurs started by researching the industry, looking for overviews of the business of veterinary practice. They found almost nothing. No books. Just one publication from the American Veterinary Medical Association, a 1½-inch-thick compilation of statistics.

The men talked to veterinarians who were personal friends, and arranged visits to various practices. “Honestly, the hospitals I saw I wouldn’t buy now,” Art said. “They were old and smelly and stuff. … Not all of them, but a lot of them were not, if you think about it, as modern as they are now.”

By chance, someone recommended they speak with Drs. Richard Gebhart and Pat Sevedge, owners of one of the largest animal hospitals in the country, West Los Angeles Veterinary Medical Group. “Bob tried to call Richard for weeks, and he never took the call,” Art recounted. “And then one day, he did.”

Gebhart and Sevedge had been running the hospital, by then a 24-hour-a-day endeavor, for nearly 20 years. In an interview, Gebhart described being receptive to the overtures. “I didn’t want to get stuck in (one) practice all my life,” he reflected. “I wanted to do different things.”

VIN News Service photo

Neil Tauber, co-founder and senior vice president, deflected concerns that VCA would dominate veterinary

private practice, saying: “My guess is we’ll always be a microcosm of the profession. I think the

individual practitioner will always be out there. I think our company will grow but in a measured way.”

Meeting Bob over lunch, Gebhart found him and his team credible, and liked their ideas. “I knew veterinary medicine had to go beyond what it was,” Gebhart said. “To grow a practice and render the service that was needed for quality patient care and excellent service required a considerable investment.” Moreover, Gebhart knew of no veterinary practice owner with the means to purchase the hospital.

The businessmen, in turn, were impressed with the operation. “When we walked in, it was a three-story animal hospital with an elevator and ORs (operating rooms) around-the-clock,” Art said. “It felt like a real business. It felt modern, and like, wow, this might be possible.”

Thus in 1987, the startup whose founders adopted a name reflecting their ambitions, Veterinary Centers of America, made their first acquisition. Gebhart stayed for five years to help the newcomers learn the business, during which time the company picked up another dozen hospitals and went public. While Gebhart obviously liked VCA’s executives, other veterinarians observing the acquisitions did not.

The hostility and derision weren’t subtle. Bob recalled: “Here we were, three guys from New York City. They used to call us the Pep Boys — Manny, Moe and Jack — and other unkind things.”

The attitude, he said, was: “ ‘What are these people doing in our industry? What are these people doing in my hospital?’ Whatever it was, it wasn’t going to be good. Whatever it was, we were cheats, liars and thieves.”

Enriching the competition

Today, VCA has a reputation for buying quality practices and providing good care. Its interest in full-service veterinary medicine is exemplified by the state of its first and now flagship hospital in Los Angeles, which in 2013 moved into a redesigned former Automobile Association of America building on South Sepulveda Boulevard, two blocks from the hospital’s original location. The 42,000-square-foot facility is nearly three times bigger and includes parking for 250 vehicles.

Matching and in some instances surpassing facilities for human medical care, the gleaming veterinary hospital, remodeled and expanded at a cost of more than $20 million, offers nearly every type of service and specialty available in companion animal medicine, from critical care to acupuncture, oncology to physical therapy. Asked as he showed off a linear accelerator whether there was any piece of diagnostic equipment he wanted that he didn’t have, the medical director Dr. David Bruyette answered instantly, “No.”

Looking at what the hospital he started has become affirms for Gebhart the role he played in launching VCA. He firmly believes the company’s presence has benefited the profession by increasing the value of practices. “They’ve put a lot of liquidity into the marketplace. You’ve got to give them credit for that,” he said.

Besides, if it hadn’t been VCA, another corporate player would have come in, he maintains. “Someone was going to do it,” Gebhart said. “You’re better off dealing with someone who has the ethics of VCA. They do a great job in practicing quality medicine.”

Yet VCA’s investment in facilities and client services and its deep pockets only sharpens the fear among some of its independent competitors.

A clinic owner who received an offer to merge with VCA was at first puzzled by the invitation because the letter specified practices within two miles of a VCA, and hers is farther than that. She thought, “Hell, maybe they’re planning on converting somebody within two miles of me. And then I was scared, thinking they’d open something that’s big, beautiful and has 10 times the money I have.”

The veterinarian asked not to be identified out of fear that VCA somehow would retaliate. “I’m honestly afraid they’d come after me,” she said. “If they can buy out every practice around them — you don’t mess with someone who has that much money.”

Antipathy toward VCA stems in part from a general mistrust of large corporations.

On a message board of the Veterinary Information Network (VIN), an online community for the profession, a member posting anonymously a few years ago spoke anxiously about the clinic where he worked being bought by VCA. “I see more and more VCA hospitals and wonder if we will all be working corporate one day,” the veterinarian said, adding speculatively, “I think VCA may be a fine employer, but you will need to give up some freedoms and toe the company line.”

On another message board, Dr. Robert Weiner, a veterinarian in New York state, commented in 2011, “I suppose I live in the past, but I hate to see veterinary practice go the way of the pharmacy and the family farm. The vertical monopolization of the profession will one day make me an anachronism. (I might already be one.)”

Weiner was reacting to VCA’s purchase of the practice communications and marketing firm Vetstreet. He said he planned not to use Vetstreet because “There are several large practices in my area that I think would be good targets for VCA in the future, and I dislike the idea of supporting my probable future competition.”

(Weiner noted last month that his practice still uses Vetstreet because of the effort involved in switching but that he may explore a competing program in the near future.)

The same aversion to enriching the competition led Dr. Keith Gold, a veterinarian in Maryland, to cancel a long-term contract with Antech Diagnostics. The move provoked a lawsuit — one of at least 26 such suits filed by VCA in the past three years, contributing to its image as an aggressive behemoth.

“I’m unhappy with VCA buying everything out,” said Gold, who is fighting the suit. “… VCA has bought several hospitals in the area. I just don’t think I should be funneling money to them.”

VCA Senior Vice President of Development Tauber is mindful that the company cannot afford to antagonize independent clinic owners, for fear they would reject relationships with VCA divisions such as the diagnostic laboratory, the most lucrative branch of the company.

“We try to be friendly,” he said. “It’s true, we walk this fine line because Antech services in excess of 10,000 practices. If they felt we were predatory, they wouldn’t do business with Antech.”

How big?

The growing domain of VCA Inc.

Whether seen as cordial or cutthroat, VCA hospital acquisitions will continue.

“We’re a hospital-acquisitions company,” Doug Drew, vice president of U.S. hospital operations, said simply. “We’re not going to not buy hospitals.”

(On a smaller scale, VCA sells and closes hospitals, as well. Drew said the company sold two last year, an activity he called rare. The company’s 2013 annual report states that it operates 609 hospitals, but updated information from VCA gives the number as 608.)

Describing VCA’s approach in soliciting prospective sellers, Tauber said: “We call veterinarians blindly, we send mailers, we advertise in journals, just to get our name out there. It’s never hostile.”

Said Bob Antin: “I have never bought a practice from a doctor who didn’t say ‘yes.’ We don’t force anybody to sell.”

In seeking mergers with small practices, Tauber said company representatives have made overtures to clinics near VCA hospitals for two or three years now through cold-calls and visits. A year ago, the company began sending mailers to practices it identified via Internet searches and by tapping the knowledge of its own veterinarians in the urban and suburban communities in which the company likes to locate.

For each VCA hospital that has the capacity to absorb more doctors, staff and clients, the company scouts for potential candidates. Tauber said the process is ongoing.

The company is eyeing clinics with as little as $400,000 in annual revenues — considerably less than the $1.2 million-revenue-clinics it seeks for outright purchases.

Bob Antin has this picture of the types of practices that would respond favorably to the solicitation:

“I would imagine … that in the United States, there are a lot of hospitals that the physical plant is old. Run down. (Owned by) doctors who have worked their asses off for years and years and years, and they have a hard time hiring somebody because they don’t want to work in unattractive facilities.”

Antin imagines that when VCA asks, “Hey, would you like to practice out of a nicer facility and work with other medical people?” the doctor suddenly has an out.

“Four hundred thousand dollars, that’s a small facility,” he said. “What are you going to do with that? ... Nobody wants to buy that.”

If the letters had gone solely to dilapidated clinics owned by exhausted, dispirited veterinarians, perhaps they would have been uniformly welcomed. But the invitations hit more widely than that.

One recipient opened his clinic only two years ago, taking care, he said, to locate “a ‘professional courtesy’ distance” from other practices. One year later, a VCA hospital that had been two miles away in another town moved next door.

“Now, they send me this letter wanting to buy me out,” he told the VIN News Service by email. “That is some nerve! VCA has no professional courtesy and I go out of my way to be sure I don't do business with any of their associated companies. I would never sell my practice to them. I find these letters somewhat predatory, especially in light of my situation …”

The veterinarian asked not to be named, saying he doesn’t want “to stir the pot,” but agreed to be quoted to “(let) others know my story so they can keep their eyes wide open in dealings with VCA.”

He added that his practice is thriving, thanks in part to clients who are “anti-corporate and actively supporting my small practice.”

“My biggest problem is explaining to new clients which animal hospital they are making an appointment at, and where to go,” he said.

Another veterinarian who was offended by VCA’s offer to buy offered an alternate financial vision to the one laid out by company executives. “The reality is that small practices have low overhead and can be quite profitable,” she said. “...Our business model is more focused on the community in which we live, rather than on the pure profit motive …”

A practice owner since 2000, the veterinarian said she has “made enough money that so far, my retirement plans are set. I didn’t include selling my practice into the equation because years ago, I knew that with escalating student debt, there would be fewer people that could afford to buy practices. … However, I know that my place is small enough that someone could afford to buy it, because there are still good loans available to veterinarians.”

Not every recipient has reacted with repulsion to VCA’s overtures, of course. Dr. W. Greg Upton, a practice owner in Texas, said, “I really didn’t think that much about the offer, just chunked it.”

Both VCA and Banfield Pet Hospital — an even bigger chain-clinic owner largely located in PetSmart stores — operate near him. “I’m not a fan of corporate medicine; it isn’t for me,” Upton said by email. “But I don’t fret about it. I also have a SNAP (Spay Neuter Assistance Program) not far away. They probably take more business from me than either VCA or Banfield. …

“This is a free country and they are free to open a practice where they like and charge what they want,” Upton continued. “Competition is good for the whole even if some individual businesses are adversely affected. I hope corporate medicine does not completely dominate the profession in the future, but at least they compete from a level field. I’m more resentful of the nonprofits deviating from their origins into direct competition with practices….”

Ed Guiducci, a veterinary business lawyer in Colorado, said VCA’s mailer campaign may be new but the concept of buying a practice minus the building and equipment is not. “They want patient and client records, and they want the seller to stay around to transition the clients to a new location,” he said. “This is a long-standing approach not just by VCA.”

As for soliciting desired clinics by mail, Guiducci said, “I don’t see it as offensive. It’s analogous to a homeowner in a hot area who wants to find a house to buy, but nothing’s for sale so they send a letter to all the neighbors: ‘If you happen to want to sell, let me know.’ ”

Asked how many invitations drew interest, VCA’s Tauber said he couldn’t say offhand. “What I can tell you is, on my desk right now, I’m doing, hang on —” he paused, counting. “Currently, I’m in documents on five right now that want to merge. There’s many more that I’m waiting for financials.”

One veterinarian’s experience

Sometimes the company woos an independent owner for years. The owner might even be someone with a skeptical opinion of VCA. Bob Antin pointed to Dr. Wallace Graham as a case in point.

Graham started a practice from scratch in Corpus Christi, Texas, in 1982 at the age of 30. Another veterinarian opened a hospital 2¼ miles away. That hospital eventually was bought by the company Pet’s Choice, which in turn was acquired in 2005 by VCA. Twice, Graham was invited to merge — first by Pet’s Choice, then by VCA. Twice, he declined.

In 2011, VCA bought Vetstreet, extending its domain to online marketing and client communications. Like many independent practice owners who were Vetstreet customers, Graham worried that the data Vetstreet possessed on his clinic would be used by VCA to sharpen its hospitals’ competitive edge.

Graham called Vetstreet to express his concerns. The man who answered said he would have Bob Antin return the call. “Yeah, right,” Graham thought.

But Antin did call. He was genial and said that “they weren’t good enough to be able to mine the data and use it to their benefit,” Graham recalled. And supposing they could, Graham remembers Antin saying, “If anybody ever caught us at that, we’re dead. All of our businesses are dead. We can’t risk that.”

Graham found the reply persuasive. “I wasn’t sold on the nature of the company at that point,” he said, “but I thought, ‘Either this guy is a really, really nice guy, or he’s a very slick salesman. … Or both.' ”

About that time, Graham was nearly 60 and thinking about how to position himself for retirement. He took steps to move his hospital to a larger building, intending to make the business more marketable in the future to a corporation. But the endeavor was more expensive than he anticipated. Coincidentally, the nearby VCA hospital was in the midst of expanding. The medical director there, a longtime friend, raised the idea again of merging. This time, Graham agreed.

The friend was key, Graham said: “Had he not been there, I would not have talked to anyone. That relationship was critical.”

The practices merged in 2012. VCA offered jobs to the whole staff, with no pay cuts. Most accepted but few stayed. Graham chalks it up to the different environment — going from a practice with 16 employees to a practice with 60. “It was a lot more like a family in a small practice than a big practice,” he said. “Some of them just didn’t like it."

Some clients left, as well. Graham estimates that more than half remain, but a “substantial” number were lost, due at least in part to VCA’s higher overall prices. (One thing Graham learned while competing as a practice owner is that corporate prices aren’t necessarily lower. “There’s an extra layer of management, so fees have to be adjusted to deal with that,” he said.)

As for what it’s like working for VCA, Graham says that no matter where he practices veterinary medicine, “I love what I do.”

‘Certainly not Starbucks’

Despite its perceived high rate of acquisitions, VCA is a long way from controlling the market, Tauber maintains.

Whether it’s hospitals, laboratory work, digital medical equipment or practice communications, VCA has at least one big competitor, if not numerous competitors. “In no marketplace do I think we have a monopoly, or come close to that,” he said.

In the veterinary hospital realm, Tauber figures that the vast majority — more than 18,000 out of an estimated 21,000 to 26,000 practices in the United States — remain independently owned.

“At any one time, there’s only 1,500 to 2,000 practices that are targets of ours,” he said, based on size, location and practice type. “We like to be in urban/suburban places. We do very little large animal. If you look at our growth over 20 years, it’s not colossal growth. … It’s certainly not Starbucks by any means.”

The figures he presented explain why VCA believes much room remains for the company to grow at home. Asked whether VCA aspires to establish itself in foreign countries beyond Canada, Tauber said, “We talk about it. We’ve looked at Europe. But there’s still so much opportunity in America.”