Photo courtesy of Becker Medical Library, Washington University School of Medicine

This building at Washington University, photographed circa 1928, housed the School of Dental Medicine until its closure in 1991.

After being appointed to dean of the dental school at Washington University, Richard J. Smith learned during his first meeting with the chancellor that the 123-year-old dental program might close.

He’d had no inkling this was coming. “I was shocked,” he remembered.

But at that time, Washington University School of Dental Medicine in St. Louis would not be the first to close, nor the last. It was the fifth of seven dental schools in the United States to shutter between 1986 and 2001. They were discontinued for multiple reasons, including tight budgets, questions of relevance to institutions’ academic missions and — most significantly — declining student applications.

What didn’t cause the closures was any sort of orchestrated effort by the dental profession to address worries about a market oversupply of dentists.

Yet that is an enduring popular belief among members of other professions plagued by an apparent mismatch between numbers of new graduates and available jobs, stagnant salaries and crushing educational debt.

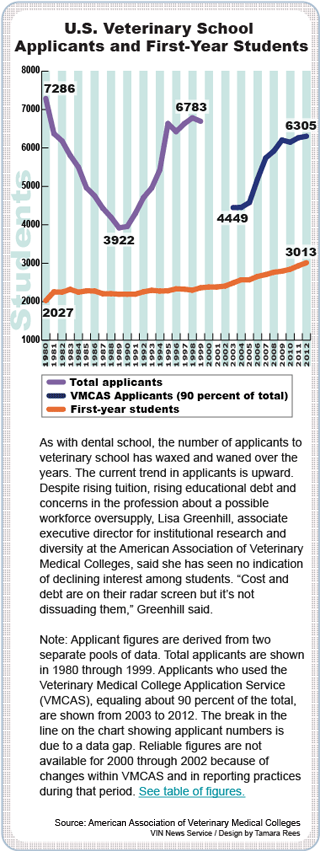

Veterinary medicine is a case in point. On the Veterinary Information Network, an online community, members discussing the state of their profession periodically wonder why veterinary medicine can’t do as the dentists did and close some schools until demand and incomes rebound.

As one wrote recently: “In a perfect world, our profession would shut down the schools’ output of graduating DVMs until our salary levels reached an appropriate level. … This curtailing of supply to keep demand at a ‘livable’ level is what the dentists did 20 years ago (or so).”

Within the legal profession, which is in a comparable fix, some members similarly perceive that the dental profession exerts better control over output of new members. In a May 2012 report, the Massachusetts Bar Association’s Task Force on Law, the Economy and Underemployment states that “... dental schools appear to regulate the volume of their graduates.”

The truth is that dental schools, like all colleges and universities, operate independently from the professions for which they train. The decisions to close schools were made individually by their parent institutions. “There was no guiding hand behind this at all,” said Dr. Richard Valachovic, president and CEO of the American Dental Education Association. “Things just happened.”

The truth is that dental schools, like all colleges and universities, operate independently from the professions for which they train. The decisions to close schools were made individually by their parent institutions. “There was no guiding hand behind this at all,” said Dr. Richard Valachovic, president and CEO of the American Dental Education Association. “Things just happened.”

Local circumstances propelled closures

Each school was driven by its own economic reality. At Washington University, which closed in 1991, a key factor was an inability to compete with public dental school tuition rates, according to Smith, the dean to whom fell the duty of overseeing the transition to closure.

Smith recalled that Washington University dental school tuition was about $20,000 a year in the late 1980s, compared with about $6,000 at the University of Missouri - Kansas City School of Dentistry, 250 miles west of St. Louis.

The tuition disparity might not have mattered if plenty of students were eager to enter dental school. That was the case in the mid-1970s, when 15,000 applicants competed for some 6,000 slots, making for a healthy applicant-to-seat ratio of 2.5-to-1.

But by the 1988-89 academic year, when Washington University decided to eliminate its dental school, the national ratio had fallen to 1.26-to-1, a historic low. Put another way, there were four seats for every five applicants.

That meant dental schools were faced with the prospect of taking lackluster students, including some with unimpressive grades and less-than-sterling test scores.

Private schools such as Washington University were under an additional pressure. Smith noted that unlike in medicine, law and business, the culture of dentistry does not emphasize the importance of attending prestigious institutions. He mused that veterinary medicine may be similar to dentistry that way.

“Think about it. Do you care where your dentist went to school? … Nor do (people) choose a veterinarian on that basis,” he said. “… We don’t have that kind of hierarchy. Great students won’t necessarily travel to go to a dental school. If they’re a wonderful student in Memphis, Tenn., they’re unlikely to pick up and go to Boston.”

For a private school aspiring to attract the academic elite, having to take mediocre students was unacceptable. Smith recalled his chancellor expressing a view that the situation was inconsistent with Washington University’s long-term strategic plan.

In the years leading up to school closures, dentists in private practice were concerned about business, or what was termed “busy-ness,” Valachovic said. Many worried they did not have as many appointments as they could serve. But that concern did not directly influence school closure decisions.

As a professor and chair of the orthodontics department and then dental school dean, Smith said he was unaware of what was happening in the private practice economy. “I was so internal to the educational process that I was not familiar with the business end of the private practice issues,” he said.

“The closure of dental schools … had absolutely nothing to do with recommendations from a national dental association,” Smith added. “A university is not terribly concerned about that. (A decision to close) is entirely internal to the university.”

Public perceived dentistry as dying

Dr. Eric Solomon also had a close-up view of the school closures. At the time, he served as assistant director for application services and resource studies at the American Dental Education Association. “I was the one who had to tell everybody what was happening with their applicant pool,” Solomon said. “The applicant pool was falling off the table.”

Solomon believes that only a drop-off in student demand compels a decision as momentous as closing a school. “As long as you have the demand for the profession, it will be hard for the profession to say, ‘We need to cut back,’ ” he said.

“It is my thesis that until the applicant pool is affected, nothing will change,” he continued. “The educational associations, the professional associations and the institutions themselves do not have a vested interest in reducing enrollment.”

And what drives student demand? In Solomon’s view, it is public perception of an occupation’s job outlook.

“Case in point,” he said: “The New York Times has issued very interesting articles (recently) on the profession of law. It’s illustrated how lawyers no longer can graduate from law school and get a job in the field of law. They’re also having trouble paying their student loans. It’s a bloody mess. Now the law school applicant pool is falling precipitously.

“What occurs in the popular press is very powerful,” Solomon said. “Be careful what you write about; it might have a real big impact on what goes on.”

In dentistry, a 15-year decline in student applications started in the mid-1970s. From a historic high of 15,734, applications fell below 5,000 by the late 1980s.

Solomon and others attributed the decline to the widespread belief that dentistry was a dead-end career, owing to the success of fluoride in toothpaste and water in preventing cavities.

“It was having a dramatic impact on the rate of dental disease in permanent teeth in children. When these data became widely circulated, some in the popular press wrote, ‘When dental disease goes away, why do we need dentists?’ ” Solomon recalled.

Missions and valuable real estate

Valachovic, head of the American Dental Education Association, recalls the period of school closures as “wrenching and devastating.” On the faculty at Harvard University’s dental school at the time, Valachovic remembered: “Everybody was very scared of what might happen. Seven schools closed, and there were … maybe four or five others that were threatened but didn’t close. It was a very, very scary time.”

Valachovic, head of the American Dental Education Association, recalls the period of school closures as “wrenching and devastating.” On the faculty at Harvard University’s dental school at the time, Valachovic remembered: “Everybody was very scared of what might happen. Seven schools closed, and there were … maybe four or five others that were threatened but didn’t close. It was a very, very scary time.”

The first to close was the dental school at Oral Roberts University in Oklahoma in 1986. An article in the Tulsa World quoted an administrator pointing to student debt as the root of the problem. He said graduates couldn’t afford to go on full-time missions, a central goal of the Christian school.

The second institution to close its dental school, Emory University in Georgia, reportedly faced conditions similar to Washington University. An account on Emory’s website states: “… a diminished need for dentists nationwide and increased competition from state dental schools founded in the neighboring states of Florida and Alabama led the university to phase out its DDS program.” The school closed in 1988.

Two more followed in 1990, at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., and Fairleigh Dickinson University in New Jersey. Loyola University of Chicago closed in 1993.

By the mid-1990s, the dawn of cosmetic dentistry brought new life to the profession. Nova Southeastern University College of Dental Medicine opened in Florida in 1997. However, the trend in closures wasn’t quite over. That same year, Northwestern University officials announced a proposal to close its venerated, 110-year-old dental school.

The Chicago Tribune reported that “demand for dentists is rising,” but Northwestern officials had other concerns. According to the Tribune, the dental school was viewed by university leadership as lacking the “cachet of Northwestern’s other professional schools.”

“We want to focus our resources into the areas that are among the best in the country,” Alan Cubbage, vice president of university relations, was quoted as saying. “… even though the caliber of students applying and attending our dental school has improved, it’s come down to the question of, ‘Are we the best in that area?’ ”

Dr. Simmi Kapur, a Northwestern alumna who graduated in 2000, one year before the dental program was eliminated, remembers from meetings of the university president with students receiving a strong impression that “he personally held (dentistry) in low regard.” In an interview with the VIN News Service, she recalled, “He … felt there wasn’t a need for more tooth carpenters.”

Moreover, the dental school occupied prime real estate on the shores of Lake Michigan in a historic part of Chicago known as the Gold Coast, said Kapur, who practices in the region. Kapur understood that the university hoped to use the dental school property for more lucrative work, such as medical research, which could attract grant funding, as opposed to “draining money as a dental clinic,” she said.

Despite her disappointment over the closure, Kapur added that Northwestern made the transition conscientiously. “They spent a lot of money on keeping morale up,” she said “… All the faculty got retention bonuses if they stayed until the end of school closure, and everybody was very, very accessible.”

Institute of Medicine examined dental education

The Institute of Medicine (IOM), part of the National Academies, took an in-depth look at dental education during the period of closures. In a report published in 1995, "Dental Education at the Crossroads: Challenges and Change," the IOM panel observed that “the dental profession is at odds with itself” on a variety of matters. One source of tension, matched today in veterinary medicine, was this:

“The dental community is characterized by much anxiety and disagreement about whether the nation faces a future shortage or oversupply of dental services.”

“The dental community is characterized by much anxiety and disagreement about whether the nation faces a future shortage or oversupply of dental services.”

The IOM committee traced the issue to the 1950s and 1960s, when concerns about a shortage of physicians and other health professionals led to the passage of the Health Professions Educational Assistance Act of 1963. The act provided grants to schools for construction and expansion, and loans to students.

The federal government continued in the early 1970s to increase funding for dental schools. Between 1971 and 1975, six new dental schools were established.

Then in 1976, a national report warned of too many medical schools. “Congress reacted to the changing view of the health care supply question … by reducing direct support for health professions education, including dental schools,” the report recounts.

“The whipsaw effect of adopting and then removing a significant stimulus for enrollment growth had disruptive effects on both educators and practitioners that still persists in debates about the size, distribution and composition of the dental workforce and the appropriate number and size of dental schools.”

The IOM committee wasn’t able to settle the question, either. It “found no compelling evidence that would allow it to predict” either shortage or glut. Therefore, it made no recommendation to either increase or decrease dental school enrollments.

Despite the committee’s finding of tension in the profession over workforce size, Dr. Carlos Manuel Interian Jr., one of two private practitioners on the 18-member panel, said the school closures brought no cheers from practicing dentists.

“On the contrary, they were quite disappointed,” Interian said in an interview with the VIN News Service. “All in all, it was the practicing community that truly came out in support of trying to maintain these schools. It was very ironic.”

Twenty years since the era of closures, dental education is expanding once again.

Since 1997, nine schools have opened; another four are scheduled to open by 2015, bringing the total number of U.S. dental schools to 66.

The number of annual dental-school graduates today, about 5,200, is below the historic peak of 6,300 in 1977, reflecting smaller class sizes than in the past, according to Valachovic of the American Dental Education Association.

Still, the pace of growth is reawakening worries about how much is too much. Valachovic said the debate within the profession about the “right” number of dental school seats and graduates is ongoing “and without resolution.”

Smith, the former dental school dean at Washington University, has a doctorate in anthropology and today serves as dean of the university’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. Contemplating the boom-bust cycles of his former profession, Smith observed, “We do that with everything, with building shopping malls and building condos. When it looks like a good thing, we build too many and then everyone suffers. It seems to be the American way.”