LMU horse model

VIN News Service photo

The equine laboratory at Lincoln Memorial University School of Veterinary Medicine is located at a teaching center in Ewing, Virginia, 12 miles from the main campus in Harrogate, Tennessee. Ewing, in Lee County, is categorized as an economically "distressed" area.

Ask a sampling of alumni from the first class to graduate from Lincoln Memorial University College of Veterinary Medicine whether the program emphasized opportunities in rural practice and encouraged them to work in underserved communities of Appalachia, and the answer almost uniformly is yes.

The experience reflects efforts to educate veterinarians for careers in rural America, a founding principle of LMU's Veterinary school. The program opened in 2014 in Harrogate, Tennessee, near the heart of Appalachia. The region, stretching 205,000 square miles from southern New York to northern Mississippi, commonly is characterized by beauty and poverty. Access to veterinary care in some parts of Appalachia is scarce.

By LMU's count, 27% of the class of 2018 were living and working in Appalachia, and 34% were practicing in large-animal or mixed-animal practices as of last fall, according to a university news release. The group comprises 87 graduates.

How much the college's emphasis influenced new graduates' choices of practice type and location is, however, less definitive. Interviews with 16 alumni suggest that a variety of factors outside of academia's sway — from economics to family ties to gut feeling — played key roles in where graduates landed.

LMU's quest to steer its students toward particular geographic regions and specific areas of medicine tests a popular concept that veterinary schools can be an effective tool in addressing shortages. Time and again, universities seeking to establish veterinary programs cite a desire to bring needed veterinarians to their regions.

For example, a pending veterinary school partnership between South Dakota State University and the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine focuses on rural medicine and is premised in part on the prospect of bringing graduates back to South Dakota to practice. A feasibility report on the project states:

"A collaborative program in rural veterinary medical education meets a regional need for additional veterinarians, contributes to continued growth of the animal-agriculture industry, creates a direct pathway to veterinary careers for South Dakota students, and strongly addresses veterinary student debt load, a significant consideration for future practitioners."

Similarly, Texas Tech is pushing to start a veterinary school, in part, to serve veterinary medical needs in the Texas Panhandle. The move is opposed by Texas A&M University College of Veterinary Medicine & Biological Sciences, which is based in College Station, an eight-hour drive from Texas Tech's campus in Amarillo. Texas A&M worries that a second program in the state could siphon resources from the existing veterinary school.

Few graduates land in distressed or at-risk counties

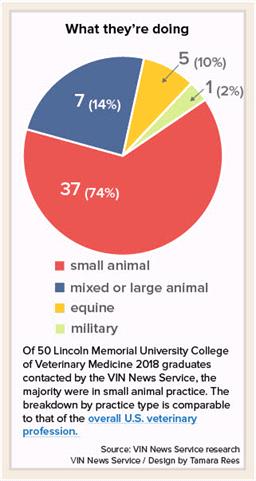

To learn more about the LMU experience, the VIN News Service reached out to 85 LMU veterinary college alumni and was able to confirm — through contact with the individuals or their practices — the professional status of 50 graduates, and where they practiced at the end of 2018.

To learn more about the LMU experience, the VIN News Service reached out to 85 LMU veterinary college alumni and was able to confirm — through contact with the individuals or their practices — the professional status of 50 graduates, and where they practiced at the end of 2018.

Of the 50, 11 were practicing in counties that are part of Appalachia, as defined by the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC), an economic development agency established by Congress in 1965.

The geographic region roughly follows the spine of the Appalachian Mountains, taking in all of West Virginia and parts of 12 other states. Appalachia lags behind the country in average household income and health.

The LMU Center for Animal and Human Health in Appalachia (CAHA) quantified the shortage in 2015 in a 200-page report, which showed that 1,907 veterinarians were needed in the region and 75 out of the 420 counties in Appalachia faced veterinary shortages.

(When it was released, the report was greeted with skepticism by some who perceived that the authors employed an arithmetic trick to reach their conclusions about a veterinary workforce shortage. Viewed a different way, the numbers they presented also could support a conclusion that Appalachia had more than enough veterinarians to serve the population.)

Appalachia is not uniformly under economic duress. But it has an outsized share of what ARC calls “distressed” counties. Eighty-one counties rank among the most economically depressed in the country, based on a three-year average of unemployment, per capita market income and poverty rates.

Other categories are "at risk," "transitional," "competitive" and "attainment." For comparison purposes, ARC applies designations to all counties in the country, not just those in Appalachia.

Of the 11 LMU graduates whom VIN News confirmed were working in Appalachia, one was practicing in a location — Clay County, Kentucky — defined as distressed.

Three other graduates practiced in counties categorized by ARC to be at risk of becoming distressed: Overton County in Tennessee, and Honaker and Scott counties in Virginia.

The other seven veterinarians were in counties rated as transitional, meaning somewhere between economically strong and weak. This is the most common designation in the country; 50% of counties in the U.S. are considered transitional.

Of course, economic duress occurs outside Appalachia, as well. Two graduates were practicing in distressed counties in other parts of the country. Most of the rest were working in counties categorized as transitional or better. One was in the U.S. Army.

Rural practice strongly encouraged

Sixteen LMU graduates answered VIN News questions by phone or email. The vast majority confirmed that LMU's curriculum stresses opportunities in rural and large-animal medicine; and that the school encourages graduates to stay in Appalachia and work in underserved communities.

"The emphasis on rural practice really came through during fourth-year rotations," said Dr. Jordan Bradley, who works in a mixed-animal, on-call emergency practice and makes farm calls in Omak, Washington, in a transitional county.

A Washington native, Bradley thought when he left home for undergraduate studies in Oregon that he’d never return. "But after eight years away," he said, "I decided I wanted to come home."

Dr. Amanda Gann Thomas works in Appalachia as an associate veterinarian at a two-doctor mixed-animal practice in Smithville, Tennessee. Smithville is in DeKalb County, which is classified as at-risk. Personal reasons led her there.

"I chose to practice in this area due to its being within driving distance of the house my husband and I built while on his family's farm," she said.

Nebraska native Dr. Danielle Becker relocated to North Dakota after graduation. She’s now in a mixed-animal practice, predominantly working with beef cattle. The county where Becker is located is ranked among the economically strongest in the country.

Becker said she would have considered staying in Appalachia, but the places where she interned weren’t hiring. The move to North Dakota also allowed her to apply for the state’s veterinary loan repayment program, which could cover as much as $80,000 over four years.

Loan repayment programs can make a difference for veterinarians interested in rural practice by easing the burden of education debt. About eight out of 10 graduates of U.S. veterinary schools in 2018 had student loan debt, according to the Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges. The median debt was $177,000. Among LMU graduates specifically, the median was $256,000.

One LMU graduate, Dr. Travis Gilmer, won a grant this year from the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Veterinary Medicine Loan Repayment Program, which pays up to $25,000 a year toward the education loans of veterinarians who commit to serving in a designated veterinarian shortage area for three years. Gilmer works at a mixed-animal practice in Gate City, Virginia, located in a county identified as at risk.

But there aren't enough loan repayment grants for everyone. Dr. Matthew Lamare who hails from Lewiston, Maine, said, LMU "tried to push as much as they could to promote large-animal medicine." But the school couldn't alter the financial realities that influenced his career choice. Lamare works in an emergency practice in Lexington, Kentucky, located in a transitional county. “Unfortunately," he said, "to make money you have to be [in] small animal [practice]."