When recreational marijuana became available legally in his state in 2015, Dr. Rick Hill began fielding questions from clients wanting to know whether their ailing pets could benefit from pot.

Unsure how to respond, the veterinarian in Happy Valley, Oregon, contacted his state veterinary licensing board for guidance. The regulatory agency’s carefully worded email reply that it could not advocate the use of medical marijuana in veterinary patients confirmed for Hill that the issue is fraught with risk.

The problem is that state laws allowing marijuana use, whether for medicine or pleasure, apply to people. They do not address non-human patients. Marijuana remains illegal under federal law, which classifies the drug as having a high potential for abuse and no accepted medical value. So even in jurisdictions where marijuana is legal, without a specific authorization for veterinary use, veterinarians are not protected in recommending its use.

At the same time, anecdotes abound of pet owners trying it, often with positive results, and products marketed for pets are proliferating. This puts veterinarians in a predicament. Many worry that they risk their licenses by discussing and exploring marijuana use in animals. But by evading the topic, veterinarians potentially leave owners to medicate their animals without guidance, putting the pet's health at risk.

That’s what worries Hill. On a message board of the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession, he said recently: “For me, the product is now as available as Starbuck’s coffee in Portland, so we had better start discussing its potential use with clients so they can be open and honest about it, as opposed to the client experimenting on their own.”

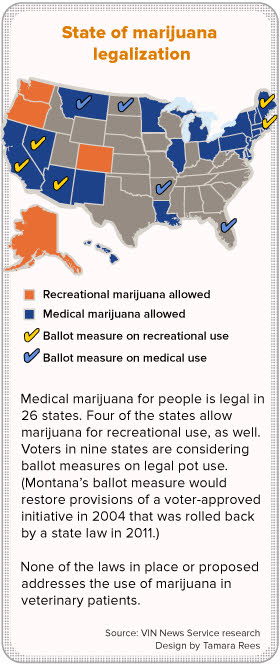

The conundrum promises to become more common as marijuana legalization spreads. On Tuesday, voters in California, Nevada, Arizona, Maine and Massachusetts will decide whether to allow recreational pot. Approval across the board would more than double the number of states permitting recreational use. Colorado and Washington were the first, in 2012, to legalize the recreational use and retail sale of marijuana. Oregon followed, then Alaska, where the state’s first retail pot store opened Oct. 29.

Another 22 states allow medical use of marijuana, and three more states are considering ballot measures next week to do the same. (A fourth state voting on medical marijuana, Montana, already permits it but the scope of the law is in dispute.)

As the question of pot for pets faces more practitioners, outside of veterinary circles, the issue induces giggles. In Nevada, which allows medical marijuana, a bill introduced in 2015 to authorize veterinary use attracted national media coverage that tended toward comic in tone. The bill died quickly.

“It became … just a big joke,” said Sen. Tick Segerblom, a Democrat from Las Vegas who sponsored the legislation.

Pet pot was just one piece of an omnibus bill meant to refine multiple aspects of how Nevada managed medical marijuana, Segerblom said, but it drew all the notice and became something of a distraction. He had hoped that pet owners wishing to legitimize veterinary medical marijuana would have a chance to explain their position in a hearing, but the bill never received an airing.

“The theory was that veterinarians could prescribe it for dogs with the thought that they would try to do some independent research to determine what works and dosage and things like that,” he said. “The problem is, everybody was talking about it [trying pot on pets] but veterinarians weren’t willing to do it because they’d be breaking the laws.”

The lawmaker said he plans next year to revisit the issue from a different angle. The bill taking shape would prohibit professional licensing boards from taking disciplinary action against licensees because of licensees’ professional involvement with marijuana.

Research stymied

It’s well understood among veterinarians that ingestion of cannabis, the plant from which marijuana is derived, can be toxic to dogs. Problems from accidental exposure are amply documented. As in people, the bodies of dogs and other animals naturally produce cannabinoids. These chemicals, whether natural or from an outside source such as the cannabis plant, attach to receptors in the nervous system, immune system and elsewhere, to affect the body’s function.

Attempts to determine scientifically whether marijuana has medical benefits in dogs, cats or other pets, and if so, for what conditions and in what amounts and forms, are stymied by conflicting state and federal laws and lingering stigma.

The federal government's classification of marijuana as a controlled substance has had a chilling affect on research. Due to drug-enforcement restrictions, most federal research dollars are allocated to studies on abuse and addiction.

Dr. Dawn Boothe, a professor of physiology and pharmacology and director of the clinical pharmacology laboratory at Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine, has tried to obtain private funding for research, with as yet no success.

“Studies are really, really expensive,” Boothe said. “To study one product in a dog — [that is], in a series of dogs where there’s enough animals to make a difference, that’s at least six — that’s a $25,000 study. Who’s going to pay for that?”

Because of federal prohibitions on marijuana, obtaining product for research purposes is difficult, as well.

“In the meantime, now we have all these products that are showing up that have no, and I mean zero, evidence of quality, efficacy or safety,” Boothe said.

Cannabis products for pets come in myriad forms: capsules, biscuits, chews, oils, and topical gels, to name a few. Ingredients and concentrations vary, as well.

According to Boothe, the cannabis plant has more than 70 different cannabinoids, or biologically active molecules, the most well-known of which is tetrahydrocannabidiol (THC), the substance that causes a high. THC is found principally in the flowers of the plant.

Another cannabinoid gaining popular recognition is cannabidiol (CBD). The allure of CBD is that it’s associated with as many potential medical benefits as THC but thought to have much less of a psychotropic effect, Boothe said.

Also in CBD’s favor is that it can be extracted from hemp, a cannabis subspecies that is low in THC, the compound associated with addiction.

The industry, however, lacks uniform standards. That means a product marketed as having CBD, THC, other cannabinoids, or a blend, may or may not actually contain those ingredients.

“The population needs to be educated as to what these products cannot promise,” Boothe said. “Right now, they can’t promise anything. They can’t even promise that what the consumer thinks they’re buying is what they’re buying, because there’s nothing to regulate the content.”

Moreover, she said, “We also do not know if the compound is absorbed, and to what extent.” Before researchers can begin to answer questions such as whether cannabis helps control seizures, decrease vomiting or kill cancer cells in dogs and cats, they need to know what compound they’re administering and whether it is absorbed. “And we can’t, with confidence, because there’s so much variability,” Boothe said. “We have measured cannabinoids in some of the animals receiving these products, and the amount [of active ingredient] the animals are getting is all over the board.”

Results of U.S. Food and Drug Administration tests of several commercial products purported to contain cannabinoids highlight the potential for fraud. “[T]hese products are not approved by FDA for the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of any disease, and often they do not even contain the ingredients found on the label,” the agency said. “Consumers should beware purchasing and using any such products.”

The agency sent letters in early 2015 to six companies, including two that market products to pets, warning that the health claims the companies made suggested that the products were drugs, yet the products had not been approved by the FDA for sale as drugs. The FDA sent similar letters to eight more companies in early 2016.

Veterinarians in cannabis industry

One business that received a warning letter in 2015 was Canna Companion LLC, which is owned and operated by a wife-and-husband team of veterinarians in Washington, Drs. Sarah Brandon and Greg Copas. The company sells cannabis for cats and dogs in the form of capsules containing powdered whole hemp sourced from California, Canada and the Netherlands.

The couple’s interest in cannabis as medicine for animals dates back nearly 20 years. Brandon said Copas had a variety of health problems stemming from childhood sports injuries and, following difficulties with conventional painkillers and anti-inflammatory drugs, began researching the potential of marijuana as a substitute. The two met in the late 1990s while attending veterinary school at Oklahoma State University. Brandon said they obtained marijuana illegally and began testing forms and dosages on Copas as well as on their pet and foster dogs.

“We would try it cooked, we would try it raw, we would try it dry, not heated. And we’d start to see different benefits and negatives,” Brandon recounted.

After graduating in 2002, they moved to Washington, where they continued experimenting. “We rescued and fostered I don’t know how many animals, and every one of the animals that came into this household, they got it” whether ill or not, Brandon said. “I wanted to see how it worked in normal [healthy] animals.” She added: “We knew what to look for for their safety. We knew what to look for for their well-being.”

By then, Washington voters had approved medical marijuana. Brandon and Copas obtained authorization to grow plants for one of their veterinary assistants. They also began recommending cannabis to some clients. Their expanding experience and the further liberalization of marijuana laws in the state led to the founding of Canna Companion in 2014.

The warning letter from the FDA did not impede the business but only prompted the company to revise language it uses to describe potential effects of the product, Brandon said. She perceived that the regulatory agency was concerned with the nature of the health claims, not the product itself.

For example, “We were saying ‘helps control pain in patients with osteoarthritis,’ ” Brandon said. “That is unacceptable. We’re making an FDA drug claim using a non-FDA approved product. What we say now is, ‘Can assist mobility in dogs with normal aging joints.’ It’s vague enough, and it doesn’t say how you’re assisting the mobility or imply a specific underlying condition other than a normal aging process.”

Brandon said the company informed the FDA of the changes it made and received a letter of acknowledgment. “That’s it,” she said. “So we just keep moving forward!”

FDA spokesman Michael Felberbaum said the case is not closed but did not elaborate, noting, “The FDA cannot comment on ongoing compliance matters.” He provided a link to general information on the agency’s perspective on marijuana as medicine.

Brandon and Copas work full-time at Canna Companion now and do not see patients regularly, although Brandon gives free consultations to pet owners who are giving their pets cannabis products — any products, she said, that are certified by an independent laboratory to contain the ingredients claimed and in the amounts claimed.

“It has been my experience that pet parents that are interested in this, they are beyond grateful to have a veterinarian to talk to,” Brandon said. “I’m just trying to provide a little safety and guidance.”

Brandon said she and Copas maintain records of all animals they’ve known to have cannabis exposure, in the neighborhood of 4,000 pets. Most are dogs and cats, but guinea pigs, skunks, pot-bellied pigs, ferrets, birds and horses are represented, as well.

Another veterinarian who has ventured into the cannabis arena is Dr. Robert Silver, an alternative-medicine practitioner in Colorado and president of the Veterinary Botanical Medicine Association. Silver was propelled into the field by pet owners. After Colorado legalized medical marijuana in 2000, clients would come into Silver’s practice attesting to the advantages of marijuana over manufactured pharmaceuticals.

Trigger

Photo by Dr. Robert Silver

Trigger, who had a variety of ailments, was the first dog Dr. Robert Silver treated with cannabis extract. Silver overdosed his pet on the first attempt. That unsettling experience taught him to test animals’ tolerances with very low initial doses.

Silver said he was skeptical at first, figuring they were experiencing a placebo effect.

Then he began to see effects in pets. He’d have, for instance, a patient with mobility problems caused by arthritis, and he would try remedies such as acupuncture, physical rehabilitation and Chinese herbs. When the pet improved, Silver credited his treatment until the owner confessed, “Well, Doc, we shared a little bit of our stash with him.”

In 2009, Silver obtained state authorization to grow plants so he could make an extract for his father-in-law, who was dying of prostate cancer. Silver observed that the extract, given along with other medications, eased his father-in-law’s pain.

After that, Silver tried a homemade cannabis-coconut-oil concoction on his pet, Trigger, an 10-year-old rescued chocolate Labrador retriever who had bad hips and knees and was recovering from heartworm disease as well as the surgical removal of a eye due to glaucoma. The first time Silver gave Trigger cannabis, the concentration was too high. The dog became shaky and disoriented; he cried out and barked through the night. The incident “really freaked me out,” Silver said.

But Silver dared to try again, reducing the dosage by 75 percent. To that, Trigger appeared to respond well. Silver said he put Trigger on a regimen of other herbs and supplements, acupuncture and marijuana to keep him comfortable until his death two years later.

As for how to advise clients using cannabis as medicine, Silver consulted his state regulatory board. He said he was told that because there was no means under the state law for authorizing use by a veterinary patient, he should “stay away from it.”

But clients kept bringing it up. “Clients do whatever they want to do,” he said. “In spite of the fact that I couldn’t prescribe or recommend, if I have a client coming to me wanting to know how to use something safely, it’s my responsibility to help.”

That belief led Silver to write “Medical Marijuana & Your Pet: The Definitive Guide.” Published in 2015, the book lays out what’s known and unknown about cannabis exposure in animals and gives detailed instructions on making extractions at home and figuring out effective dosages.

“I think education is the best medicine; that is why I did that,” Silver said.

He’s aware he’s taking a risk but is willing to at this point in his career. He’s been retired from daily practice since 2010 and serves as the chief medical officer of Rx Vitamins For Pets, which makes nutraceuticals, including a hemp product, for sale to veterinarians.

Doors opening?

In August, the Oregon Veterinary Medical Examiners Board emailed this message to its state’s licensed veterinarians:

Questions have been raised about veterinary use of cannabis; at present, Oregon does not have rules addressing this. For the time being, here is the Board’s advice:

Veterinarians may discuss veterinary use of cannabis with clients, and are advised to inform clients about published data on toxicity in animals, as well as lack of scientific data on benefits. Please be aware that a client’s written consent is needed for any unorthodox treatment.

Lori Makinen, executive director of the board, said the statement was prompted by a legislative task force that recommended regulatory boards inform licensees of the board’s position on the subject. Coming up with a position that the board as a whole could endorse was not easy.

“We went around and around and around on this for over three meetings,” she said. “It was kind of crazy … We started out with quite a bit of text, and what I ended up with was the two sentences.”

Hill, the veterinarian in Happy Valley, Oregon, is intrigued by the last part of the statement, “written consent is needed for any unorthodox treatment.” By his reading, it “suggests that they are opening the door for its use, but it’s a back door.”

He’s witnessed the veterinary community becoming more receptive to the concept in other settings, as well. “In some recent conferences/talks I’ve been to, they are now discussing the use of CBD/hemp oils in patients openly …” he told the VIN News Service by email.

To his colleagues on the VIN online discussion, Hill observed, “It will be interesting, to say the least, to watch this unfold.”

Update: Following Election Day Nov. 8, California, Nevada, Maine and Massachusetts joined states permitting recreational marijuana use, bringing the total to eight, plus Washington, D.C.

Legal medical marijuana spread to Arkansas, Florida and North Dakota, for a total of 29 states, plus Guam and Puerto Rico. (Some tallies of states allowing medical marijuana put the number at 28 because they do not count Louisiana, which has a law that is considered unworkable or marginally so.) Also on Election Day, Montana voters rolled back restrictions on an existing law authorizing medicinal use.

This article was changed from the original to correct statements about the principal source of THC in cannabis, and the relationship between hemp and cannabis.