VIN News Service screenshot

On its website, Animal Humane New Mexico emphasizes that its veterinary clinic serves only low-income pet owners, explains why and elaborates on the qualifications.

Click

here for larger view

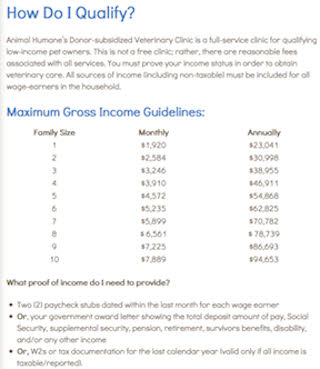

At Animal Humane New Mexico, owners of pets seeking subsidized care at the nonprofit shelter’s veterinary clinic must meet specified income limits and prove it by producing pay stubs, tax documents or comparable statements.

Requirements at San Diego Humane Society are less exacting. No paperwork is needed in exchange for low-cost spay/neuter services, only the owner's word that he or she is strapped financially.

And "affordable services for pet owners” are available to all in the nation's capital, where the Washington Animal Rescue League places no income restrictions on those seeking veterinary care.

The size of the welcome mat at nonprofit veterinary clinics is a source of friction in the veterinary profession, where a prevailing sentiment among private-practice owners is that the growing nonprofit sector encroaches unfairly on their businesses.

Capturing the thoughts of many of his colleagues is this comment by Dr. Harold Steve Kaser, a solo practitioner in Delaware, Ohio: “Just doesn’t seem fair that a local group (humane society) as a tax-exempt organization can offer discounted services in competition with tax-paying vets.”

His comment appears on a message board of the Veterinary Information Network, an online community for the profession, where the issue comes up time and again as nonprofit animal-welfare organizations grow in number and add or expand veterinary services.

A common view of private-practice veterinarians is this: Because nonprofits pay no income taxes, and benefit from donations and volunteer labor, any veterinary care they provide to the public should be limited to pets whose owners can’t afford market rates. Moreover, clinics should enforce the restriction vigilantly.

“It's a pity when clinics don't means test, because my personal opinion is that low-cost and free clinics have a definite place in our society for those most vulnerable,” said Dr. Erin Hicks, a private-practice veterinarian in Tacoma, Washington. “People who fraudulently use these services divert resources from those who truly need them and cannot pay full cost for them. I think of it as stealing from taxpayers, generous donors and those animals who really need care.”

Among nonprofits, the idea that subsidized medical care should be targeted to those who otherwise can’t afford care garners broad — though not universal — support. But rigorous verification is a different matter. Why? Because means testing is complicated, time-consuming and expensive.

“It’s way harder than it sounds,” said Dr. Gary Weitzman.

Weitzman is a former medical director and CEO of the Washington Animal Rescue League. At the time he led the Washington, D.C.- based clinic, the organization devoted considerable effort to verifying the eligibility of would-be clients.

“We had two receptionists who literally spent their entire day on the phone with prospective clients to make sure they had the right information and right answers to be serviced at our clinic,” Weitzman said. “It was costly to have our staff members doing that. The information they could get was invariably incomplete. It was almost impossible to prove that someone could use the clinic. It was terrible. It didn’t help anyone, and especially, it didn’t help the animals.”

Nonprofit-sector growth raises private-sector anxiety

- The number of organizations identified by the Internal Revenue Service as animal-protection groups was 20,170, according to a search on Guidestar, a database on nonprofit organizations. By comparison, the number in 2008 was 11,500.

- The estimated number of shelters is 3,400; in the mid-1960s, it was 600.

- Total income in the animal protection movement increased 4.5- to five-fold during the past 50 years. Including expenditures by municipal animal-control agencies, the estimated total annual spending today for animal control and protection is $4 billion.

Concluding the system was impossible to manage, the organization gave it up. “We could do a lot more good for people and animals by not spending $100,000 on staff a year just so they could screen people to not get services,” Weitzman said.

Today, the Washington Animal Rescue League clinic has no income barriers to service. That’s not a policy Weitzman endorses, either. Now CEO of the San Diego Humane Society and SPCA, Weitzman occupies a middle ground in the tug-of-war. He believes animal-welfare organizations should limit services to those truly in need, and that those clients must be trusted to identify themselves.

“We are here to help those who need us, not to help those who are able to get care somewhere else,” said Weitzman, whose career history includes seven years in private practice.

Explaining San Diego Humane Society’s approach, Weitzman said: “If you make less than $44,000 and (have) this number of dependents, you can bring your animal in. We ask, ‘Do you have any (documentation) from the state?’ They can just tell us, they never have to show it.”

How the organization enforces the rule is more direct than requiring paperwork, Weitzman said: “We look them in the eye.”

Some will lie, he acknowledged. But he believes that most won’t. And those clients who do lie “aren’t the ones that a private practice wants, anyway,” Weitzman said.

Moreover, requiring documentation doesn’t eliminate lying. “Anybody can bring in documents that don’t tell the truth,” he said.

“Everyone feels so exasperated when they see someone leave a (discount) spay-neuter clinic in a Lexus,” he added. “(But) we’re not here to make judgments about what people drive, and maybe a deceased parent left them a Lexus.”

Group motivated to maintain good relations

Animal Humane New Mexico takes a different tack. Clients wishing to bring their pets to the veterinary clinic must show two paycheck stubs dated within the past month for each wage-earner in the household; or a government award letter showing the total deposited amount of pay, Social Security, supplemental security, pension, retirement, survivors benefits, disability and/or any other income; or W2 forms or tax documentation for the previous calendar year, provided all income is taxable and reported.

Clients are asked each year to demonstrate eligibility, said CEO Peggy Weigle. “We tend to re-qualify our clients on an annual basis because things change in life,” she said, adding, “Sometimes our clients get annoyed with us (about that).”

Nevertheless, clients generally are reasonably good about producing the required paperwork, she said — if not right away, then at some point in the process.

“If they come in with an emergency, we will try to work with them because our priority is helping the pet,” Weigle said. “They need to bring (the papers) next time, or when the pet is picked up, assuming the pet is hospitalized.”

What motivates the organization to enforce income guidelines diligently is finances, Animal Humane New Mexico explains on its website:

“With the exception of our euthanasia services, which we offer to all pet owners to avoid unnecessary suffering of pets, you must qualify. Given that Animal Humane receives no city, state or federal funding to offset our annual $4.5 million dollar operating budget, we limit our services to pet owners who otherwise would not gain access to quality veterinary care for their beloved pets.”

Weigle said the clinic costs $1.2 million a year to operate, of which 55 percent is covered by fees for services, 23 percent by donations earmarked for the clinic and 22 percent by donations to the organization at large. She estimated that clients pay one-third what they would be charged in private practice, on average; the subsidy varies by service.

Another reason the organization limits its clinic services to low-income households and requires proof of eligibility is for the sake of peace. Its board, Weigle said, “wants to maintain good relationships with our veterinary community.”

Revenues from full-pay clients subsidize strapped clients

In Washington, D.C., the Washington Animal Rescue League occupies the opposite end of the spectrum. Its doors are open to everyone. The organization’s website states under the heading “Affordable Services for Pet Owners” that it “… provides veterinary care to companion animals of all families, regardless of income level.”

Clients of means not only are welcome, they are encouraged to bring their business to the nonprofit clinic as a way of supporting needy animals. “An added benefit to being a WARL Medical Center client: Using our veterinary services directly supports the rescue and care of homeless animals that we shelter and find homes for,” the website says.

WARL CEO Bob Ramin said providing veterinary care to all animals, no matter their owners' means, is consistent with the organization’s mission to find homes for animals and provide services that enable people to keep their animals.

“Keeping animals is more expensive now,” Ramin said. “If we’re going to be helping to place shelter animals and homeless animals, we also need to focus on keeping the animals healthy.”

In the past, WARL veterinary care was available only to income-qualified clients, and staff meticulously verified eligibility. But effective January 2014, the organization adopted a completely different model of service.

“We have opened up our practice to anyone who would like to come,” said Ramin, a former vice president of fundraising at the National Aquarium in Baltimore who joined WARL in late 2012. “That’s a trend in the industry, where rescue organizations that have full-service medical centers are opening up to help subsidize some of the things they do.”

WARL has a two-tiered fee system — one for qualified low-income clients, and one for everyone else. “Our ‘regular prices’ I would say are a little under (market rate), but they’re competitive,” Ramin said, noting that an annual exam runs $60. “I wouldn’t say that they’re inexpensive. Health care for animals is not inexpensive.”

Clients whose annual income is $55,000 or less are eligible for discounts of 30 percent or more, depending upon the service. Those clients are asked to demonstrate eligibility by bringing W-2 forms for all wage-earners in the household or Social Security statements. But if they don’t, WARL doesn’t press the issue.

“We’ve decided not to put as many resources into confirmation of this, and more (resources) into providing the services,” Ramin said. “It’s really an honor system. We want to build up our practice. At some point, if we’re turning the people away in droves, we’ll focus more on that.”

Although WARL has, in the words of its website, “a busy, full-service on-site veterinary clinic and medical center,” Ramin said he does not consider his organization in competition with private veterinary practices in the vicinity.

“We’re not going to put out of business any of these fine veterinary centers,” he said “… We don’t have the specialists on-site, and some of the state-of-the-art equipment that some of these other places have.”

‘I inherit this’

Much like WARL, the San Francisco SPCA provides discounted veterinary care for clients who apply for help, at the same time that it serves all comers at market rates.

“Our hospitals are unique in that they are basically like a social enterprise,” said Dr. Jennifer Scarlett, a veterinarian and co-president of the organization “We’re not a low-cost hospital. Clients pay full price, and the revenue that is generated from that goes to support providing grants and basically, interest-free payment plans for guardians in need. So for the person who doesn’t need financial assistance, they don’t get the discount. They’re coming in because they’re getting a fantastic hospital and a good feeling to know that their revenue is going toward keeping animals in their homes.”

The San Francisco SPCA has two chief reasons for opening its doors as widely as possible.

One is that people may have a legitimate need for assistance even if they’re not officially low-income. “Say you’re two paychecks away from (being broke). You’re not poverty level, but you’re having trouble making ends meet,” Scarlett posited. “There are so many variations of this situation that we should have flexibility in how we address these very individualized circumstances.”

(In the fiscal year that ended June 30, the SPCA Mission Campus Hospital provided interest-free payment plans to some 1,300 clients, equaling about 6 percent of its clientele, according to Shade Paul, the director of hospital services. Another 325 received grants for emergency care or senior-citizen discounts. The SPCA Pacific Heights Hospital, acquired through a merger with Pets Unlimited in 2014, and the SPCA spay-neuter clinic have different programs.)

Another reason for serving as many people as possible relates to the SPCA’s mission to find homes for pets and keep them there.

Said Scarlett: “If you run a progressive shelter where you’re treating animals and rehoming them, if someone gives up their animal because the animal was hit by a car and fractured its leg and they (the owner) doesn’t qualify under means testing but they can’t afford the treatment, the nonprofit takes on the cost of that — of keeping them in the shelter. …

“It costs thousands of dollars plus a lot of heartache ... a cost … that the (private-practice) veterinary community never sees.”

To those who would argue that people who can’t afford pets shouldn’t have them, Scarlett responds: “I get that, but there’s an animal who needs my help, and without it, I inherit them. When you’re stuck right there — ‘I inherit this‘ — that changes the conversation.”

Turning away a pet owner because of a perception that the person is irresponsible with money doesn’t solve the problem in any case, she said: “I’m willing to step in if that animal is not in a good place. I’m going to be an advocate for that animal’s welfare. To take on everybody’s poor spending habits, as well as take on a condition that I’m going to treat and have to rehome, and this person’s going to go right out and get another dog, then what have I accomplished?”

That the issue has caused a rift between veterinarians working in private practice and those in nonprofit and government service is unfortunate and unnecessary, Scarlett believes. “We’re not here to undermine veterinarians. We value and love veterinarians,” she said. “We are veterinarians.”

She continued, “I believe there is room for private practices and nonprofits to come together and talk about, what are we trying to preserve? What are we trying to achieve in this work, and where can we partner?”

Professional association treads carefully

At the American Veterinary Medical Association, a policy statement about nonprofit practices acknowledges the value of tax-exempt clinics for providing “access to important medical and surgical services for animals owned by the indigent and otherwise underserved populations.”

On means testing, the policy uses this delicate wording: “Where applicable, means testing to determine eligibility should be conducted in compliance with each organization’s internal documents for clients accessing veterinary services.”

Asked to elaborate, Adrian Hochstadt, AVMA director of state relations, said, “We have different views in the profession about that. That’s why it’s difficult to come up with one concise, easy statement. We have members who work in shelters, and we have members in private practice.”

The policy stops short of saying that all nonprofit clinics should means test. Instead, Hochstadt explained, it urges organizations with policies to serve only low-income clients to “follow your own policy, to be consistent with your charitable mission.”